A bespectacled, slightly rumpled man with a radio-announcer voice, Jeff Gerst is animated, funny and passionate about biology. Even so, he has struggled with teaching in large lecture halls. "In the past, I would ask a question, nobody would know the answer, and so I'd wind up picking on the people in the front row," Gerst says.

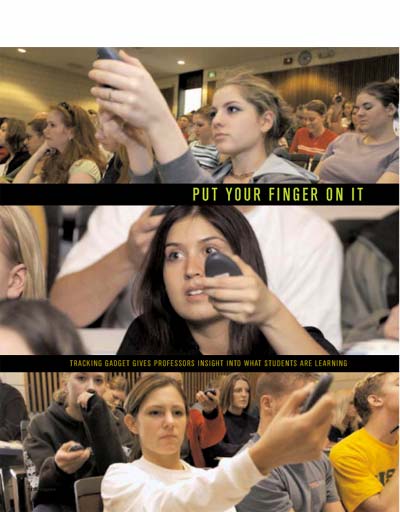

A new technology helps Gerst keep track of every person in a large class, including the students nodding off in the back. Gerst is one of many teachers on campus who use the wireless personal response system that packs enormous potential.

The system — palm-sized transmitters, portable receivers and software — requires every member of a class to answer the instructor's questions. Students use the transmitters to register their answers and, if they're feeling especially bold, their confidence level with the answers.

The system tallies the students' responses, projecting a bar graph on a large screen. The display tells students if they're getting a concept, and teachers if they are conveying it.

By now, it's obvious this technology is about more than gee-whiz gadgetry. It's about something that many educators on campus have committed to: a renewed emphasis on learning.

The commitment seems so obvious as to be laughable. Isn't that automatically the No. 1 goal of any educational institution? Still, many people who study pedagogy, or the science of learning, maintain our old system isn't working.

They say the traditional mode — one person lecturing, students taking tests based on memorized, soon-forgotten facts — does not engage today's young minds, which were reared amid the interactive, non-linear world of cyberspace.

Problem-based learning represents a whole different pedagogical approach. It veers from passive listening and memorization to participation and problem solving. It looks at big pictures and multi-disciplinary methods vs. rigidly defined subject areas and the accumulation of isolated bits of data.

At NDSU, the charge for problem-based learning — or "PBL," as acronym-happy academia calls it — is led by Sudhir Mehta. A long-time professor of mechanical engineering, Mehta taught in the traditional vein for years, until a 1991 education conference changed his life.

There, nationally respected educator Patricia Cross spoke about the process of learning. "The real intellectual challenge of teaching lies in the opportunity for individual teachers to observe the impact of their teaching on students' learning," Cross told the audience. "And yet, most of us don't use our classroom as laboratories for the study of learning."

From that point on, Mehta began to turn his attention from the science of robotics and computerized machine vision systems to the less calculable science of learning. Now, as associate vice president of academic affairs at NDSU, Mehta is in a prime position to influence the university's culture of learning. "With the (traditional) type of model, there is very little engagement or problem-solving or challenge," Mehta says. "In real life, your boss is not going to come and tell you, 'OK, this is chapter 1, this is how it works and I'll give you an example from the end of the chapter.'"

Nationally, NDSU is a rarity for the number of instructors qualified to teach this way. In the Upper Midwest, the university stands alone.

Students report the little gizmos force them to try harder during lectures. More importantly, the interactive tools make students show up in the first place. Attendance numbers rise 40 to 45 percent when the units are in use.

Not all students like it. Many are used to a traditional classroom setting, and are not thrilled about a strange new world of learning beyond the textbook. Mehta tells of a senior-level course he based entirely on PBL. "They said 'it's too late for us to learn now in this different way.' "

"Hopefully, we will grow that culture so resistance is very minimal," Mehta says. It's a culture that could eventually stretch far beyond college campuses.

"If we can somehow start changing so the curriculum is somehow more engaging, more connected, more real-life," he says, "then

I think it will be more fun for students and teachers."