It's hard to keep up with Tama Duffy, even when she's wearing high-heeled leather boots that would make the feet of a lesser woman whimper. The 42-year-old is speed-walking through her Capitol Hill neighborhood in Washington, D.C., in the middle of a brilliant and chilly Friday afternoon. The air is almost as brisk as Duffy as she heads from the Metro station to her home. Cell phone in hand, she is speed-dialing, too, checking messages en route to her meeting with an air conditioning contractor - worried that she might already have missed him.

It's hard to keep up with Tama Duffy, even when she's wearing high-heeled leather boots that would make the feet of a lesser woman whimper. The 42-year-old is speed-walking through her Capitol Hill neighborhood in Washington, D.C., in the middle of a brilliant and chilly Friday afternoon. The air is almost as brisk as Duffy as she heads from the Metro station to her home. Cell phone in hand, she is speed-dialing, too, checking messages en route to her meeting with an air conditioning contractor - worried that she might already have missed him.

Duffy, a 1980 design grad, is one of the latest additions to the team at OP.X, an edgy D.C. strategy and design firm. She's at her best leading high-powered teams of architects and interior designers on complex building projects. She can go head to head with major contractors without blinking an eye. And this project today is no different - only this time Duffy's client is Duffy herself.

Duffy, a 1980 design grad, is one of the latest additions to the team at OP.X, an edgy D.C. strategy and design firm. She's at her best leading high-powered teams of architects and interior designers on complex building projects. She can go head to head with major contractors without blinking an eye. And this project today is no different - only this time Duffy's client is Duffy herself.

The AC guy is upstairs, Duffy's electrician tells her when she reaches her classic 150-year-old wood-framed row house. She charges up the narrow steps - temporarily sans banister - to the second floor while the electrician continues to calmly work. He's installing track lighting - small, multi-faceted halogens to brighten up a room that gets only the soft light of morning. Duffy had called the home a demolition zone. It's true. There's an elegant black velvet sofa half covered with plastic in the middle of the room. Other pieces of furniture - a table and several chairs - are huddled up next to it, trying to stay out of the way. Yet despite the Men at Work feel, it's clear that there's a gracious, welcoming home coming into being.

Standing in the front living room, you can see straight through the dining room and kitchen (also under construction), past the bright Caribbean-blue mosaic walls of a tiny downstairs bathroom all the way to the sunny, terraced brick garden. Duffy moved to D.C. from New York City at the end of the summer and lived in the house for a couple of weeks watching, as she says, "how the sun penetrated the spaces." She thought about how natural light could be brought indoors - an important theme in all of her work - then drew up plans and elevations. That done, she packed her bags and moved in with her sister's family for three months while workers exposed brick walls, gutted the bathrooms and kitchen, straightened walls and leveled floors. She's been back in the house for a month. Even if the kitchen sink isn't yet in place and plaster dust is still flying, she's determined to get herself settled. (The upstairs bath, which is completed, helps. It's spa-like, with a bath deck that gives the original cast-iron tub the impression of being sunken, a heated, tumbled stone floor, and large custom-sized window. This is the room that speaks to Duffy's deep, contemplative nature. She's designed a place where she can soak away a tough day, look out at the stars and dream.)

Duffy's move to D.C. was a gutsy one. She had been at the top of her game in New York. Vice president and principal in charge of health care design at Perkins & Will, she'd spent 20 years building her reputation as one of the leading national experts in health care design. Now, she wasn't just changing jobs; she was restructuring her life - personally and professionally - and every bit as radically as she was her small and sturdy new house.

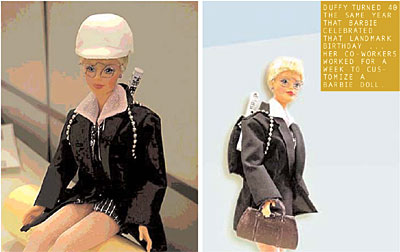

Some of the impetus for the change came from a desire to live closer to family; her sister's family and other close relatives reside in the D.C. area. Her parents' failing health back in North Dakota made Duffy reflect on her own life and take stock of what mattered most. (Her father, who gave Duffy an appreciation for beauty through his stamp-collecting hobby, took a turn for the worse suddenly in early September, passing away on Sept. 11. Her mother, who liked to paint and draw and who wrote weekly letters to Duffy while she was still able, is now in the late stages of Alzheimer's.) Still, it wasn't easy leaving behind the close relationships she'd developed with her colleagues in New York. Duffy turned 40 the same year that Barbie celebrated that landmark birthday. As a surprise, her co-workers worked for a week to customize a Barbie doll, hiding it when Duffy passed by. They cut off the hair to look like Duffy's short "do" and dressed her all in black. Then they made her tiny Tumi roll-on luggage, called her TamaBarbie, and, as a final grace note, set her up with a Ken doll, replete with blanket and bottle of French wine.

Back when Duffy was starting out, health care was only beginning to emerge as a design niche. Fresh out of school, Duffy went to Minneapolis to look for a job in commercial interiors. She landed a position in a small firm and proceeded to wrest everything she could from the experience. "I did everything from unlocking the door and making the coffee," she recalls, "to meeting with the reps, typing up specs, coordinating the library, and designing. I kind of got my fingers in every aspect of what was needed to support a project. Working for that small firm helped me to understand the entire process of design."

Her next career move was a calculated risk - a three-month contract in the Minneapolis office of Ellerbe Becket. Moving from a six-person shop to a firm of 800 could have caused culture shock in a young woman who hailed from Westhope, N.D., near the Canadian border (population 600). Instead, she thrived. "In a large firm, gathering information to do your job can be a bit like a scavenger hunt," she says. "But I liked that." There were lighting designers, architects and interior designers, not to mention the mechanical, electrical, structural and landscape engineers. They all had, Duffy says, an abundance of information: "It was a great place for me to bloom." Her three-month contract lasted for 10 years. Duffy's second project for Ellerbe Becket, the Mayo Clinic's Charlton Building in Rochester, Minn., would shape her life in ways she never anticipated. It was Duffy's first experience in health care design. In the middle of the project, the director of design left. Duffy, who describes herself as focused and intense and a product of the Midwest work ethic, took up the slack, attending all of the meetings, coordinating the team of designers. At one point, she discovered that the furniture specifications - a complex and detailed listing of the component of each and every piece of furniture, in this case several million dollars worth - were riddled with errors. Duffy started over on it, working nights and weekends nonstop to get it right.

Duffy's contributions and promise were recognized. She was asked to head another health care project, then another. "Before I knew it, I was leading teams on four projects around the country and had suddenly become a specialist," she says. She made vice president before she turned 30.

As one of the leaders in the field, Duffy's work has shown how important the components of spaces - natural light, interesting views, color palette and furniture that supports the patient, the family and the caregivers - can be in helping people feel well. But when Duffy began, health care design was not a coveted niche in interior design. In fact, it was called institutional design, reflecting interiors that took their cues from medical equipment. "I became intrigued in the practice of healing environments because they tended to be dismal," says Duffy. "Many creative people steered away from them because they felt they were too limited in terms of design solution."

The Mayo project was eye-opening for Duffy, its philosophy dating back to the turn of the century when the Mayo brothers insisted that their facilities be warm, inviting and visually friendly. "We always say that the perception of design by our visitors and patients reflects on the perception of quality and care," says Robert Fontaine, who was Duffy's client on the Charlton Building. (He's now director of planning and projects for the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. Duffy has not only worked with him on several other high-profile projects, but considers him a mentor.) Fontaine adds, "It takes more ability when you have parameters that are limiting. You have to be able to actually be more creative."

Duffy thrived on that challenge - and she's not exactly leaving that behind now. Her new challenge is to take what she knows about healthy design and apply it to other venues. At OP.X she's currently working on projects that include law offices and a hotel and conference center. "I'm interested in the whole mind/body response to environment," she says. Meanwhile, back at her own personal construction zone, the interview with the air conditioning installer, a man whose hair bears more than a little dab of Brylcreem, isn't going well. Duffy is looking for an efficient and elegant alternative to the upper story's current window units. The salesman is reluctant to problem solve with her. Whatever you want us to do, we'll do, he says. She knows there's a better answer than that, so she'll keep looking.

And maybe there, right there, is the key to Tama Duffy. She isn't afraid to keep looking until she finds the solution that works. She's a woman who can look at something - a space, a profession, a life - and see what it could be. She's given definition to her new house. She's turned her career in a new direction. How her influence will play out in the commercial world of design will be interesting to follow. That is, of course, if you can keep up with her.

- Sally Ann Flecker