"Maybe Jesus was an ice fisherman."

Someone said it between baiting hooks, eating barbecues and playing dice in the belly of the Big Fish. It came off as a gentle joke, but it presented an interesting comparison.

Jesus walked on water, had a thing for fish, and used the familiar to explain the unfamiliar. These five North Dakota State University students were "living" on the water. They aimed to preach a little gospel of art, of NDSU and the land. And they were using a fish as bait.

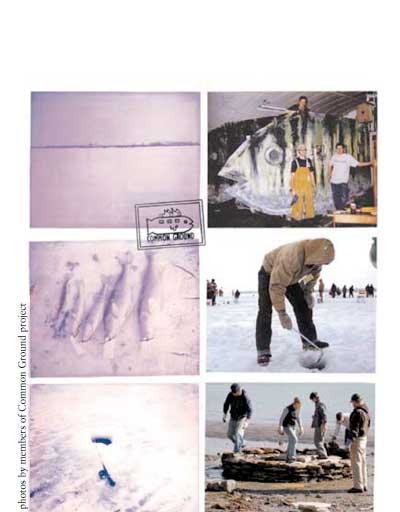

People came almost as soon as the students began assembling the Big Fish on frozen Devils Lake. It's not every North Dakota fish house that has a dorsal fin. And not every fish house is so modular in design that - on a good day - it can be put together, wood-burning stove and all, in 74 minutes flat. Nor do most ice fishermen invite visitors inside to draw pictures on the walls. So, when visitors ask "Why?" the students set their hooks and reel them in with the story of Common Ground.

It all started a few years ago with the Kellogg Foundation. "Kellogg's interest was in discovering how land grant institutions were interacting with the public and if they were still meeting the mission of being the people's universities," says Gary Brewer, who chairs the NDSU entomology department. That research evolved into the Leadership Initiative for Institutional Change or LINC, a partnership of land grant universities in North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota. "One component of the training they provide is the use of art to break down communication barriers and to get people to share their thoughts and feelings about different ideas," Brewer says. Agriculture reached out to the art department. Architecture got involved. President Joseph A. Chapman liked the idea. And so in the fall of 2001, with the help of a Kellogg grant, two Fargo artists were hired.

Jon Offutt and Terry Jelsing were selected based on their proposals for public art projects that would engage the university community and foster relationships out in the state, says Kim Bromley, art department coordinator. Offutt's project was to build a portable glass blowing studio and use it to share his expertise with NDSU students and people across the state. Jelsing invented Common Ground, a project that would introduce a corps of NDSU students to site-specific sculpture, take them on "art safaris" across the state, and engage the public along the way. While the impact of the two projects is yet to be fully evaluated, Bromley says, "I've had a couple of students tell me working with Terry and Jon have been life-altering events for them."

The lives of the Common Ground students changed the day they decided to show up for the first informational meeting. Most of them remember how they got the call. One overheard other students talking about it. A couple caught wind via email. One heard about it from a girlfriend too busy to participate herself. Before they knew it, the "chosen ones" (it was a competitive selection process) were wandering in the rain building sculpture from twine and twigs along the Red River at Fargo's Dike West.

The group's Doubting Thomas was revealed: Andrew Rising, 22, a senior in art and philosophy from Medina, N.D. "I'm the one trying to figure it out, trying to push whatever lesson there might be to its extreme, to try and get as much as I can out of it," he says. Rising did not "get" the twigs, grass and twine project, and he told Jelsing so over coffee. Jelsing said, "I'm glad you brought that up." And they talked, and they talked, and they're still talking.

A few students who began with the Common Ground team weren't able to continue for various reasons; schedule conflicts and that thing called winter graduation. In the end there were five, each with a distinctive personality and role within the group. Of course, they had no idea of what those roles would be until their first art safari on the banks of the Missouri River, near Williston. On a chilly night in early October they pitched Jelsing's outfitter's tent, stoked the wood-burning stove, and began to discuss what they, as a group of artists, would create. Jelsing, the "synthesizer of ideas," preached trust, respect and honesty and talked about how those common principles of behavior would affect their endeavor. The next day he turned them loose on the land, to scavenge and experiment with nature's materials: driftwood, brush, stone, sand. Jelsing calls them "earth sketches." They were all different, some starkly stunning in their beauty. Site-specific works like these, Jelsing says, are transitory. "The weather, the water, the sun, will change them ... In that way this brand of public art is very fragile. It's created with an intense energy and focus, it exists in time, and then it goes away or changes."

The sun went down and the serious talk began. The next day the team would collaborate on their first joint project. Guided by Jelsing, they reached a consensus: they would use the flat, sandstone rock from the shoreline to build a perfectly round disc, 12 feet wide and 3 feet high. Part of it would rest in the water. The project defined, they relaxed and listened to the cowboy poetry and songs of D.W. Groethe of Bainville, Mont., a buddy from Jelsing's undergraduate days at the University of North Dakota. A coyote wandered by and the land quietly awaited the artists' assault.

To this point, Common Ground's major projects have been extremely physical, one working with rock, the other with saws, screws and plywood. And each was executed under less than choice conditions, one cold, windy and damp, the other - in an art department Quonset - dry, dusty and cramped. The two women in the group were challenged by the physicality of the rock work and the unfamiliarity of power tools and construction, but never discouraged. They persevered for the love of the process and the camaraderie. "I kind of wimp out early if I don't have other people working with me," admits Cindy Sondreal, 24, a senior in landscape architecture from Grand Forks, N.D. "When we were picking up all those rocks, and they were talking about more layers, I knew in the end it would look great, but I needed everyone there working with me in order to keep going." Amanda Henderson, a 22-year-old architecture major/art minor from Scranton, N.D., concurs. "The thought crossed my mind that 'This is crazy, all we're doing is making a big pile of rocks,' but at the same time, it was more than that." How much more, Henderson discovered the next day. "I remember as I was walking up to it ... my heart started racing. I felt so much excitement and energy coming from the piece. It was hard to leave. I really felt personally attached to it."

The feeling was mutual. The team was forged. And they started spreading the word about the great things they had seen and done.

The momentum drew a late addition. Rick Woodland, 41, a visual arts major who grew up in Idaho literally worked his way into the group, lending a hand on the Big Fish. Selfishly, he wanted to spend a little more time around the "young minds" he'd grown to appreciate; generously, he thought he might play the role of helper perhaps even mentor. "They're becoming a unit - a small patrol," observes Woodland. "I think they could capture and dominate anything they decide to do." One might assume the main reason at artist would build a fish house that looks like a fish would be to have the joy and challenge of painting it. Not Troy Mann, 21, a fourth-year architecture student and visual arts major from Dickinson, N.D. "This is the stuff I like," he says, as he measures, cuts, fits, re-cuts and installs one of the collapsible bunks in the Big Fish. Wood and metal are more his media as an artist; as a team member his tools are honesty, a sense of humor, and a rejection of absolutes. "I'm the agitator ... the instigator. I like to disagree and play devil's advocate," Mann says. "Terry does that too. He says things like, 'Why don't you do it the opposite way of how you do it, then you'll know what it is that you do.'" Or, as Mann remembers from a philosophy class: To understand the antithesis is to understand the thesis.

The Big Fish is the antithesis of the Missouri River Project. Obvious. Gaudy. Humorous. Smack dab in the middle of Devils Lake's fishing derby one weekend in January and Shiver Fest another in February. People come to have their pictures taken beside the Big Fish. Guys in earflap caps volunteer to drill ice holes. A group of teenage fishermen from South Dakota donate a Northern pike, which is hauled back to Fargo and tested as a printing tool. Inspired, the team develops a printing project for kids, which they conduct during the Shiver Fest chili cook-off in the Devils Lake Elks Lodge. To top it off, the team wins a Sony home stereo system in the fishing derby drawing (they donate it to the art department) and the Big Fish makes newspapers across the state.

The media also covered the intimate exercise out west, and the creation will last, but it will never draw crowds. "I don't regret that the first project was not seen," says Sondreal, voicing the team view. "I feel like it was the right project to do. It came from the land. It was so perfect. It was so secluded. Our piece just reacted to that seclusion." The team's final work will likely have more in common with the stone disc than the wood fish. Maintaining the serendipitous water theme, a canoe trip is planned. Consensus is yet to be built on what they will create, but Jelsing says the students have the tools to design and execute the project themselves. "If you come from the kind of background in art theory that looks at art and life as necessary equals, then the experiences they've been part of so far would prepare them for conceiving a project and carrying it out to the end. What's been most rewarding for me is seeing the students coming together and giving up some of their own individual egos for the common good of the group. ... I think wherever these artists go, they will engage others in team art projects."

Common Ground has profoundly affected the students. Each has a high point, a low point, a point of revelation. Each confesses a deeper appreciation of the land because of the project. And each has exciting ideas of how they will apply to their own work, both now and in the future, the lessons of leadership, teamwork, art making and risk taking. But ask them - one by one - what they believe is the Common Ground, and the answer is unified: People. "If you didn't have the people, you wouldn't have Common Ground," Mann says, "the six people in Common Ground, and the people they affected, without that - in my mind - you wouldn't have anything."

-Catherine Bishop