6. Choose New Adjustment Layer, and Levels from the Layers pulldown. Okay on the dialogue box.

6. Choose New Adjustment Layer, and Levels from the Layers pulldown. Okay on the dialogue box. COMM 260, Intro to Web Design

Instructor: Ross Collins

Learning Photoshop Software (CS3)

Lesson Two: A standard routine

Levels/Curves, Dodging, Burning, Dust and Scratches, Sharpening

So far we've glanced at the tool box and palettes, experimented with image size,

cropping, and file formats, and selection tools. Now we begin working to make our pathetically inadequate

images snap to attention and help win design awards.

Generally after cropping your photo you'll want to run every picture through the tools described below in this order:

Save as to a new filename.

I. Levels

1. Download (or upload) your photo. Open your image from Bridge (or choose Open directly from Photoshop). Alternatively, download one of my own precious images I threw

on the COMM 362 web site resource page. Hm. Not a bad pic, but it could use a little work. (Couldn't we all?)

2. Crop as necessary (see lesson one). If you end up cropping so radically that

you're left with a teeny-weeny photo, consider that you'll be saving this to 150 ppi, and it has to fit into a space larger than a postage stamp.

3. Your photo is likely too light or too dark, too contrasty or too flat. Normally

a more contrasty photo prints better on newsprint, especially if it will be

run in black-and-white.

Considering the wonderful color printing we enjoy nowadays, why would anyone want to run black and white? One word: cheapandeasy. Process color (CMYK in printer's shorthand) is costly and relies on careful pre-press and printer staff for respectable results. Black-and-white can be bungled too, but not as easily, and you won't tab so deeply into your checking account on the way to the page. So graphic artists often still rely on black-and-white photo reproduction, even if the original was in color.

Note: Black-and-white images contain only one channel of color (black), and are therefore only one third as large, another advantage working in Photoshop.

Channels? What the heck? Okay, time out for a surf through Photoshop's channels. Projected color (such as that of your computer monitor) begins with black (absence of color) and adds Red, Green and Blue (RGB) in various intensities to make all colors. Full intensity of all colors makes white (I know this is not at all what you learned in art class, but there you're talking paint on paper, or reflected color). You can check this out in Photoshop by tapping into the channels palette:

a. From the Image pulldown, choose Mode, and RGB color, if it's not chosen already.

b. If the Channels Palette is not showing, choose Channels from the Window pulldown.

c. Note RGB, plus each color is shown. Click on a color to see only that channel, and observe the result.Note: if channels aren't shown in color, Choose Preferences from the Photoshop pulldown (Macintosh), Interface, and toggle on Channels in Color.

Hey, who needs hallucinogenic drugs when you have Photoshop? Of course, on our woefully inadequate laser printers you won't get those colors out at all, but a black-and-white facsimile thereof. To see what your photo will look like in black and white, under the Image menu choose Mode and Gray Scale. Thecolor you lose runs down the drain forever. What, you say, what about that History palette, to get those colors back? Oh, okay, then, choose History from the Window pulldown, and choose to step back to wherever you want to be. (I just kinda liked the idea of FOREVER, MAN, in the old versions of Photoshop.

4. Back to business. You want to control contrast. Lighten. Darken. Quicken. (Wait,

that's accounting software.)

5. Simpleton way: Under Image choose Adjustments and Auto Levels. Ta-da! Sometimes (more often than

I'd like to admit, anyway) Photoshop really is smarter than we are and just

knows what we want. You're looking for snappy shadows and strong

highlights, with detail (ability to see textures and objects) in almost every area

of the scene. To understand what this means takes practice, but you've got to

start somewhere. If Auto Levels doesn't suit you, be a sport:

do it yourself.

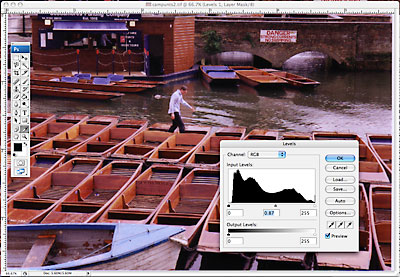

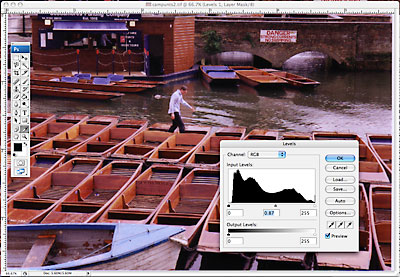

6. Choose New Adjustment Layer, and Levels from the Layers pulldown. Okay on the dialogue box.

6. Choose New Adjustment Layer, and Levels from the Layers pulldown. Okay on the dialogue box.

It's usually better to do your work on separate layers rather than alter the pixels of the actual image. A layer is the metaphorical equivalent of slapping a sheet of acetate over your work, and mucking about on that.

7. Aaak! What's that

lump of black--Dike East in silhouette? (See illustration at right.) More wondrous: it's a histogram (not

a medical term) of tones as they are distributed in your image, from highlight to shadow. Under the histogram the sliders to the left make

the darkest shades black, and to the right, the lightest shades white. Check

it out: it's the best way to understand what Levels does to your image. More

important than these, however, is that middle slider, the "gamma point."

Slide it to lighten or darken the middle tones of your image. Slide as you like,

and Okay it.

8. Using Levels on color photos

sometimes de-saturates those wonderful colors you need to make your page stand

out. One way to adjust them under the Image menu choose Variations. Pow!

Twelve images fill your screen, a fly's-eye view of life (I told you hallucinogens

were no longer necessary). Note this gives you previews of your photo adjusted for color cast.

Select the Saturation radio button

at upper right. Seven images scram, and you are left with choices for color

saturation alone. Click once or more on the labeled preview to increase or decrease

saturation. Start over by clicking on the original at top. For more drastic

or gradual changes, drag the top right slider to fine or coarse. Those odd-colored

pixels that sometimes show up mean the colors won't print (called "clipping").

Not to worry unless they begin to creep into half your image.

9. Now select the midtones button to adjust color casts. One of the most difficult

jobs of the old color darkroom technician was to precisely adjust color casts:

it takes a trained eye to notice a subtle color cast, so look carefully at your

original image, and click to try some options. Because a small change makes

a big difference, it's usually wise to adjust sensitivity slider toward the

fine side. It is true that printed color may be different from what you see

on screen.

Assignment one: print one example of your original "raw" scanned

photo, and an example of the same photo cropped and adjusted for brightness

and contrast using Levels or Curves (see below).

II. Dodging and Burning

You now have a better-cheddar photo facing you, that is, carefully cropped and color tuned. Nearly always, however, graphic artists also find

smaller areas of an image which are too light or too dark. "Too" means:

no detail. For instance, a "bald" sky, that is, pure white so it blends

into the paper when printed. Or a black hole behind a subject shot with flash

on camera. Your goal is to lighten or darken these areas to bring "detail"

into nearly every area, if possible. In Photoshop one intuitive way to

do that relies on the burn/dodge tools.

1. Click on the Dodge tool (the little paddle) in the Toolbox. This pretends

to "hold back light" as you might do under a traditional darkroom enlarger.

Wait! Don't start dragging it around your image yet. Choose Brush from the menu

bar at top, and the size you want. Now choose Exposure and Range. Exposure increases

the effect of your dragging about. Range chooses the tone (value) affected.

Adjust as necessary.

2. Drag around to lighten the area. Arggh! Too much! Choose Undo (Cmd-z).

Try it again. You need a delicate touch to avoid leaving noticeable marks.

Geezer alert: Actually,

I think this is easier to do under an old-fashioned photo darkroom enlarger.

Then, I've been doing it for 30 years.

3. Same method for the burn tool, that arthritic hand in the flyout menu that's

supposed to look like it's focusing light on an area that needs darkening. I

realize these metaphors only make sense, really, if you have darkroom background.

But like type terminology, we keep the metaphors long after we've dumped the

technology that created them. Hm. There's a master's degree thesis in that,

somewhere....

4. The third tool in that drawer, the Sponge tool, only works correctly on color

images, to decrease or increase saturation. Select Options from the menu bar

to set it up.

5. It's darned hard to get the edges of burns and dodges just right, without

that annoying line, especially when you're trying to leave a delicate touch

while manipulating a potato. That's what using a mouse as an art tool feels

like to me. Well, Photoshop gives you some options here. First you can try Fade.. Tool from the Edit menu, to soften the transition. Or use the Smudge Tool (index finger) or Blur Tool (water droplet). The Smudge

Tool is harder to control, just like a 5-year-old finger painter on your kitchen

table. The Blur Tool will give you a more precise transition. By the way, the

Sharpen Tool (elongated triangle) does the opposite, but can add a grainy edge

if you use it too much.

III. Dust and scratches (cloning)

Supposedly your picture is perfectly clean and carefully kept

in its own crisp envelope. So where did all those ugly dust spots come from?

Well, it might be from a dirty scan. But digital cameras themselves attract dust to sensors, so spots can actually be recorded digitally.

Geezer alert: Back in the old days I had to learn to spot them out using a tiny brush and

an inky substance called Spotone which never failed to spill and stain your

clothes. Ha! You oughta' pay them dues, bub. Okay, I'll let you off, but I'll

always know something you don't, nyah.

1. Under the Filter menu, choose Noise, and Dust and Scratches. In the upcoming

dialogue box, choose a pixel radius (size of dust speck) of, say, 2, and a threshold

color difference (what constitutes a speck) of 10. Note result in preview box.

2. Possibly you won't use this feature again. It's fast, but it nearly always

bullies detail out of your image, and may blur it as well.

3. Instead spot dust using the wondrous Clone Stamp Tool. This takes longer,

but works oh-so-much better. Choose from Tool Box. Choose

a smallish brush size from the menu bar.

4. Find an area roughly near the dust speck that matches its color. Holding

down the Option key, click there to set the clone point. Move to the speck,

and click. All gone now. To quickly remove a scratch, Option-click to select

the clone site, click at one end of the scratch, and shift-click at the other.

You may have to magnify to catch these details.

New to CS3: Spot Healing Brush tool. Looks like a Band-aid with circle outline. You can click on dustspots without choosing a clone point first, very cool.

Note: the clone point will move as you use the Clone stamp Tool. If you want

the point to remain where you click, toggle off the "Aligned" option

at the top menu bar.

5. If you have any lick of imagination, you've probably figured out that this

is no simple rubber stamp--this is an amazing tool that can "clone"

away anything, or clone anything onto anything else, even between two photos.

Never liked that ugly birthmark on your arm? Oops--it's gone. Kid brother giving

you a hard time? Oops--he must have been in the bathroom during your family

picture. In five minutes, I did to my head what no Minoxidil could ever touch!

(Check out this l'il charmer: Ross

with hair. ) Now you know why those magazine fashion models always look

so perfect. Warning: ethical graphic artists working in the journalism business

do NOT remove or add items not in the original scene. It is the photographic

equivalent of making up quotes. That is to say, lying. In advertising, however,

ah, whatever works....

Assignment Two: If your photo really has no dust spots to grab, Try cloning

away an object. Print a copy with and without the cloning, to hand in.

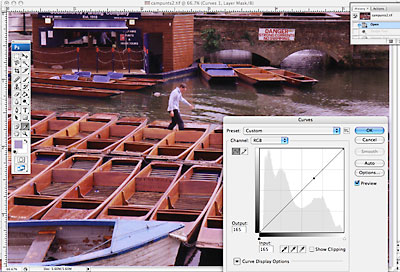

IV. Curves

IV. Curves

Now that you know how to darken or lighten prints using Levels, I'm going

to clue you in on an alternative that I think works better (There are so many

ways to do things in Photoshop that we all acquire our own preferences. You

will too.)

1. Open a photo that needs some exposure work; either it's too dark, too light, or both, and may need more detail somewhere (or even less detail in a background area). Use a photo of your own, or this (admittedly ugly) one for practice.

2. Under the Layers menu, choose New Adjustment Layer, and Curves (see illustration at right).

3. Do you see a curve? No. You see a diagonal line. Well, that's really a curve. Or it soon will be. Note that you can add a "control point" anywhere along the curve by clicking. Then you can drag, or use the arrow keys for a more delicate response, to move the curve up or down.

First Try Auto. It might just know better than you do. No? Then do it yourself.

4. Moving the curve down darkens the image. Moving it up lightens the image. (In Light Mode; you can also change to ink mode.)

5. But we're just guesstimating here, no? Why not let the program help you lighten or darken specific areas? On the photo move the cursor (now transformed into a cute li'l eye dropper) to an area you'd like to adjust. Hold down the Apple (Command) key and click. Note a control point is added to the curve.

6. Using the arrow keys (or drag), adjust the curve until the photo looks right.

7. Should this adjustment lighten or darken other areas of the photo, just adjust them as well. Command-click on other areas, and move that control point.

8. Try Curves to add detail to flat areas by increasing contrast (or vice versa).

9. If color in your photo shifts to become too garish, choose Fade Curves from the Edit menu.

V. Sharpen

Every photo needs sharpening. The digitization process adds fuzziness, but this is a kind of warm fuzzy you don't want. Generally you sharpen last, just before saving to a new file.

Geezer note: Photoshop sharpen doesn't really sharpen, you know. It just increases contrast between adjoining pixels of different colors. This works okay to pull out digitally induced fuzziness, but it is not much of an answer for people who can't hold cameras steady. In the old days we steadied a camera by bracing the eyepiece against our forehead. Nowadays people hold the camera out in their shaking fingers, peer fatuously mouth agape into the LCD display, and think they're getting a gosh-darn sharp photo. Pfff. Like Photoshop is going to pull miracles from a blurry shot.

1. Under Filter pulldown, choose Sharpen, and Sharpen. Mmmmmight do the trick, if your

photo only needs tweaking. Or not.

1. Under Filter pulldown, choose Sharpen, and Sharpen. Mmmmmight do the trick, if your

photo only needs tweaking. Or not.

3. If this doesn't do what you want, Try Sharpen Again under the same menu. Better, but not a very

well-trained pup: sharpens into "artifacts" (little flecks) on the

image some places, and not enough in others.

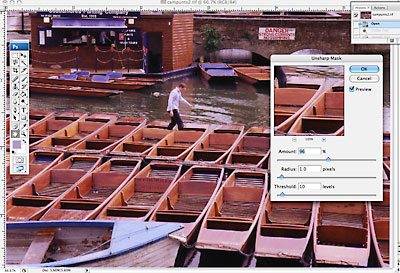

4. Undo those efforts, and unsheath some serious knives: the Unsharp Mask. (See illustration at right.) This

counter-intuitively named dialogue box is really what you need to control sharpness

of your image. You can change the amount of sharpening by percentage, and change

the Radius value to indicate the width of edges you want sharpened. Note that

a blurry photo has wide edges, so you need a higher width to make it sharp.

Generally it can be left at 0.5; try 1.0 or 2.0 if you're really working with

some Jello out there. What's an edge? That's set up by the Threshold option,

defaulting at 0 (to sharpen everything). Set it at about 10 for a smoother line. Experiment to see the results of changing

these levels. Try Smart Sharpen for even more control.

Assignment Three: Sharpen a photo. Hand in one before, one after.