Volga German History

The Volga Germans comprised a community of ethnic Germans who undertook migration Russia during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Russian government, under the leadership of Catherine the Great, invited them to settle in the area and contribute to the development of agricultural land along the fertile banks of the Volga River. Responding to this opportunity, Volga Germans originating from various German regions, such as the Rhineland, Hesse, and Swabia, proceeded to establish colonies within the region. This initiative culminated in the establishment of over 100 German-speaking villages, effectively fostering the creation of a distinct German cultural and agrarian community. While adapting to their Russian environment, the Volga Germans diligently preserved their German language, customs, and traditions, upholding their collective German identity.

- Early History

-

The displacement of Germanic people from their native lands resulted from the enduring ramifications of prolonged warfare in Germanic territories spanning nearly five generations. Following the slow reconstruction in the aftermath of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), Europe was embroiled in yet another protracted conflict. The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) was a major global conflict that involved many European powers. Initially triggered by territorial disputes in North America between Great Britain and France in 1754, the hostilities swiftly escalated into a global conflagration by 1756. Numerous battles ravaged the Hessian states, leaving vast swaths of Germany decimated in the wake of the war's culmination in 1763.

Germans were plunged into abject destitution. Their conditions were worsened by coercive military conscription and excessive tax burdens imposed by their governments to sustain the war efforts. Those who managed to survive the perils of warfare had to grapple with its aftermath – a debilitated economy and reduced food sources. Generations endured a relentless cycle of hardships until, beginning in 1763, they were offered a chance to forge a new life.

In the 1760s, Catherine II, a former German princess hailing from the principality of Anhalt-Zerbst, ascended to Empress of Russia, gaining control over extensive stretches of untamed land along the lower reaches of the Volga River. Catherine was determined to turn this region into productive agricultural land as well as to populate the area as a protective barrier against the nomadic Asiatic tribes who inhabited the region.

On July 22, 1763, Catherine issued a manifesto inviting foreigners to settle in the vast uncultivated lands of her domain. The manifesto offered settlers free land, self-government, freedom from military service, and the protection of their cultural and religious heritage. Over 90% of those who responded to Catherine's invitation emigrated from Germanic states and principalities in Central Europe. Known as the Volga Germans or Wolgadeutsche, these settlers established 106 "mother colonies" near the Volga River, near the regions of Saratov and Samara. While steadfastly preserving their distinct German cultural patterns, this initial cohort of German immigrants gradually assimilated into Russian customs and traditions. Over time, the Volga Germans became the originator of a distinct cultural group widely recognized today as German-Russians.

Image:

Oetinger, F., Flourished 1785 Artist. European Battle Scene, 1785. Courtesy of Library of Congress. - The Journey to Russia

-

Initially, Catherine's invitation garnered little attention from the German populace until 1765, when she dispatched field agents to seek out potential settlers. These field agents, known as Menschenfaenger or "people catchers," traversed the war-torn landscapes of Germanic villages, spreading the news of the invitation.

The most substantial wave of German settlement came from the Hessian states of Kassel and Darmstadt. These regions, ravaged and destitute, lived in desperation. In his book on the Volga Germans, Fred Koch said the Tsaritsa’s hunters…

“Knew where a century and a half of virtually unending wars and civil strife had left their deepest and rawest scars…they knew the areas, like the Hesses’ Odenwald and Vogelsberg, which usually yielded the poorest productivity, and where deliberately overstocked game of all species was protected and coddled to furnish sport for royal hunts at the cost of the peasants’ pitifully sparse crops.”

The promise of renewed hope propelled individuals to undertake arduous journeys spanning hundreds of miles. The peasants of the Hesse region, according to Koch, were the greatest success in Catherine’s campaign. Of the original 106 Volga German Mother Colonies established between 1764 and 1767, sixty-eight were founded by Germans from the Hesse region. From 1763 to 1768, over 27,000 colonists embarked on a journey to settle along the Volga River near Saratov, Russia.

The journey to Russia began in ports across Germanic states, all of which would go to St. Petersburg. From there, the immigrants embarked on a challenging route, traversing the Neva River for up to 45 miles until reaching Lake Ladoga. Subsequently, their voyage continued to the mouth of the Volkhov River, spanning approximately 120 miles. At Lake Ilmen, the settlers were confronted with the demanding task of carrying their belongings and provisions, including livestock, covering a distance of around 200 miles to reach suitable landing areas along the Volga River. The trip on the Volga was over 1,000 miles to Saratov, where the immigrants would then be on their way to their respective colonies.

For many families, the trip to the Volga was close to 1,500 miles and often took close to a year to complete if the weather was especially bad. The first group of immigrants did not make it to Saratov before the river froze and thus had to lodge in Russian villages along the river for the entire six-month winter. As the immigrants neared the culmination of their voyage, a sense of restlessness pervaded their spirits as they eagerly anticipated the beginning of their new lives in what they had been led to believe were well-established villages. Few were adequately prepared for the harsh reality that awaited them.

- Taking Root in Russia

After a long, dreadful journey, the settlers were hopeful that they could begin their lives anew. Instead, the German immigrants who survived the trek to the Volga region were met with an unfamiliar, almost frightening landscape. The wagons dropped them off into a sea of dry grass as far as the eye could see. There were no homes, horses, or plowed fields like they were promised – they would have to build their villages from the ground up with little to no assistance. The first settlers found almost no lumber to build traditional homes as they had in Germany. Instead, they had to move underground into "caves" or zemlyanky, where they lived in squalor conditions in cramped and damp homes. To make matters worse, many families arrived at their colonies with not enough time to plant crops to survive the winter. For the first few years, the settlers relied on a pittance from the Russian Crown, which barely covered the price of essential provisions such as grain and fish. To exacerbate matters, opportunistic locals took advantage of the settlers' desperation by inflating prices, knowing full well the extent of their vulnerability.

The harsh living conditions caused a surge in illnesses and fatalities. As noted by Koch, "In one colony of 157 persons, no fewer than 26 died in a four-month period. Entire families were wiped out in some instances." Spring, however, brought little reprieve since the rapid rise in temperature created flooding conditions that destroyed homes and property.

The administrative body entrusted with the welfare of the immigrants was the "Tutel-Kanzlei" (Chancellery Tutel), initially headquartered in St. Petersburg but soon relocated to Saratov. The locals referred to the governing body simply as the Kontor.

The Kontor, like much of government at that time, was ruled by corruption, personal greed, and a general disregard for the working “peasant” class. The immigrants found themselves at the mercy of a government that controlled their seed allocations, which, as the newly arrived settlers lamented, consistently arrived too late to be viable for germination. Adding to their plight, when the last two mother colonies were founded in September of 1767, the Kontor President Rezanov passed a law forbidding any of the settlers to participate in any industry other than agriculture. Only half of all settlers possessed a background in agriculture, with the remaining individuals belonging to an assortment of trades and professions. Under the looming threat of violence and starvation, the various tradespeople were forced to toil in unfamiliar labor.

Overall, the first few years for the Volga settlers were marked by numerous hardships. Insufficient assistance from the government hindered the establishment of a robust agricultural presence in the Volga region, resulting in meager crop yields that translated into limited income and sustenance for the settlers. Perhaps most painful was that, despite the hardships they faced in the war-torn portions of Germany, the settlers could not help but feel homesick as the promises of a brighter future seemed out of reach. It would take nearly a decade for many of the mother colonies to firmly establish themselves amidst the vast steppes of Russia.

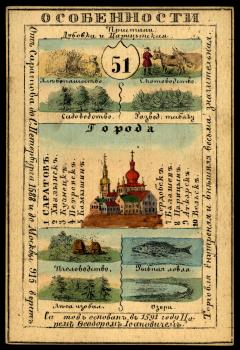

Image: Saratovskai︠a︡ Gubernii︠a︡. Russian Federation Saratov Oblast, 1856. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

- Building a New Life

-

Though the Volga Germans faced many hardships during the first generation, they slowly began to make the Volga their new home. The first truly successful crop year did not come until 1775. Following a prolonged period of drought, precipitation increased, leading to improved crop yields. This upturn in agricultural productivity gave the Volga Germans a measure of independence from the Russian Crown. Over time, the once fledgling settlers evolved into hardened people, both physically and mentally. The new generations of children knew no other home and thus did not suffer from nostalgia or homesickness. Despite the numerous setbacks, from the horrible weather to the unreliable Russian government, the Volga Germans became masters of agriculture through hard work and perseverance.

They carried their German culture, protecting it at all costs against the forces that would strip them of their cultural identity. Their culture was shielded in their isolated colonies and grew as hundreds of “daughter” colonies sprung up as the population began to rise.

- Pushed from their Homes

-

Prosperity was hard fought in the Volga region. The German settlers who had once lived in makeshift cave homes had, by the turn of the 18th century, become masters of the agrarian lifestyle. They enjoyed the fruit of their labor and the prosperity of their cultural heritage. Prosperity brought increased population, which also meant an increased need for land. Over the course of the century, the industrious Volga Germans had established numerous "daughter colonies" adjacent to the original settlements, where their offspring built new households and perpetuated the cycle. However, by the 1870s, the scarcity of land emerged as one of many factors pushing the Volga Germans to seek new lands.

In 1871, the Russian Crown revoked the Colonial Law of 1764, which originally protected the settler's land rights. It was replaced by a law that gave power to the regional political entities in Saratov. Even for the failures of the Kontor, the thought of having their legal rights in the hands of local politicians caused great fear among the Volga Germans. Historian Fred Koch said the settlers “saw in this development an intensification in the erosion of their Manifesto-granted rights and freedoms. In a single government mandate, they were lowered to the status of the Russian serfs….” No longer would their land rights be protected, nor would families be assured that their children would receive land allocations under the new laws.

Land restrictions were just one aspect of the Russian government’s attempts to strip the Volga Germans and other non-Russian settlers of their heritage. This process, later known as “Russification,” aimed to create a stronger, more “unified” Russia by replacing distinct language and culture with Russian practices. By the late 19th century, Tsar Alexander III had intensified the Russification program, leaving no aspect of the Volga Germans’ lives unaffected. The regime enforced religious practices, mandated military service, imposed heavier tax burdens, and instilled a pervasive fear of the complete eradication of their German identity.

The measures struck the heart of the thousands of Volga Germans who had come to call Russia home. They had no ill will against Russian culture or its people, but Volga Germans vehemently resisted the attempted assimilation. The confluence of land shortages, economic disparities, and the erosion of their precious heritage compelled thousands of Volga Germans to seek new opportunities in the New World.

- New Opportunities in the New World

-

In 1862, President Lincoln signed the U.S. Homestead Act, offering access to free land for individuals who were willing to cultivate and improve the land. By the early 1870s, rumors and advertisements had reached the Volga Germans. In 1873, leaders from various Volga colonies convened to deliberate on the information they had received and determine a course of action. They sent a group of exploratory emissaries (Kundschafter) whose mission was to assess the prospect in the United States and report back. The emissaries returned with soil samples, advertisements, and positive accounts that conveyed the promising life that awaited the Volga Germans in America. Traveling to the other side of the world was no small feat – even under the threat of Russification, thousands of Volga Germans remained in Russia.

According to Richard Sallet, the first Volga German settlement was established in Lincoln, Nebraska. Over time, the Volga German population in the United States grew substantially, with more than 118,000 individuals of Volga German descent residing primarily in Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska by the end of the second generation of immigrants. Volga Germans, once again, grew to be masters of agriculture in the heart of the sugar beet industry throughout the Great Plains. Like their Black Sea counterparts, Volga Germans take pride in their foodways, cherish their farmland, and value the rewards of hard work.

- Additional Resources

-

Kloberdanz, Timothy J. Thunder on the Steppe: Volga German Folklife in a Changing Russia.

Lincoln: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001. (Purchase)Heritage of Kansas: Volga Germans. Kansas: Center for Great Plains Studies, Emporia State University, 1976. (Purchase)

Walters, George J. Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben: Story of Volga Germans. Kansas City: Halcyon House Publishers, 1993. (Purchase)

Koch, Fred. The Volga Germans in Russia and the Americas, From 1763 to the Present. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977.

Long, James W. From Privileged to Dispossessed: The Volga Germans, 1860-1917. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Translated by LaVern J. Ripley and Armand Bauer. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974.

Weidenweber, Sigrid. The Volga Germans. Portland: Center for Volga German Studies at Concordia University, 2008.