Dickinson REC 2025 Annual Report

((Research Report, Dickinson REC, December 2025))Chris Augustin, Llewellyn L. Manske, Doug Landblom, Victor Gomes, Krishna Katuwal, and Glenn Martin

NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center Staff

Current Staff-2025

Chris Augustin Director/Soil Scientist

Victor Gomes Extension Cropping Systems Specialist

Cristin Heidecker Administrative Secretary

Krishna Katuwal Research Agronomist

Doug Landblom Associate Research Extension Center Specialist

Eudell Larson Ag Research Technician

Llewellyn Manske Scientist of Rangeland Research

Glenn Martin Research Specialist

Dean Nelson Ag Research Technician

Rutendo Nyamusamba Extension Conservation Agronomist Specialist

Phyllis Okland Administrative Assistant

Samuel Olorunkoya Research Specialist

Garry Ottmar Livestock Research Specialist

Wanda Ottmar Ag Research Technician

Sheri Schneider Information Processing Specialist

Michael Strode Computer Technician

Lee Tisor Research Specialist

| 2025 Seasonal/Temporary Employees | |||

| John Urban | Michele Stoltz | Chuck Wanner | Tom Grey |

| Ashlyn Williams | Anastasia Kempenich | Mary Rose | Keaton Meek |

| Lorelei Jarrett | Bailey Binstock | Ryan Duppong | Songul Senturkla |

| Felix Acevedo | Kailey Brimmer | Brae Eneboe | Miguel Torress |

Advisory Board

Edward Cuskelly-Chair

Jacob Odermann-Vice-Chair

Dustin Elkins

John Hendrickson

Ryan Kadrmas

Bill Kessel

Kevin Kessel

Mike Gerbig

Chip Poland

Lavy Steiner

Bridget Bullinger

Blake Johnson

NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center 1041 State Avenue

Dickinson, ND 58601

Phone: (701) 456-1100

Fax. (701) 456-1199

Website: https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/ag-hub/research-extension-centers-recs…

Email: NDSU.Dickinson.REC@ndsu.edu

NDSU is a equal opportunity institute.

NDSU does not discriminate in its programs and activities on the basis of age, color, gender expression/identity, genetic information, marital status, national origin, participation in lawful off-campus activity, physical or mental disability, pregnancy, public assistance status, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, spousal relationship to current employee, or veteran status, as applicable. Direct inquiries to Vice Provost for Title IX/ADA Coordinator, Old Main 201, NDSU Main Campus, 701-231-7708, ndsu.eoaa@ndsu.edu. This publication will be made available in alternative formats for people with disabilities upon request, 701-231-7881.

Table of Contents

2025 Variety Trials

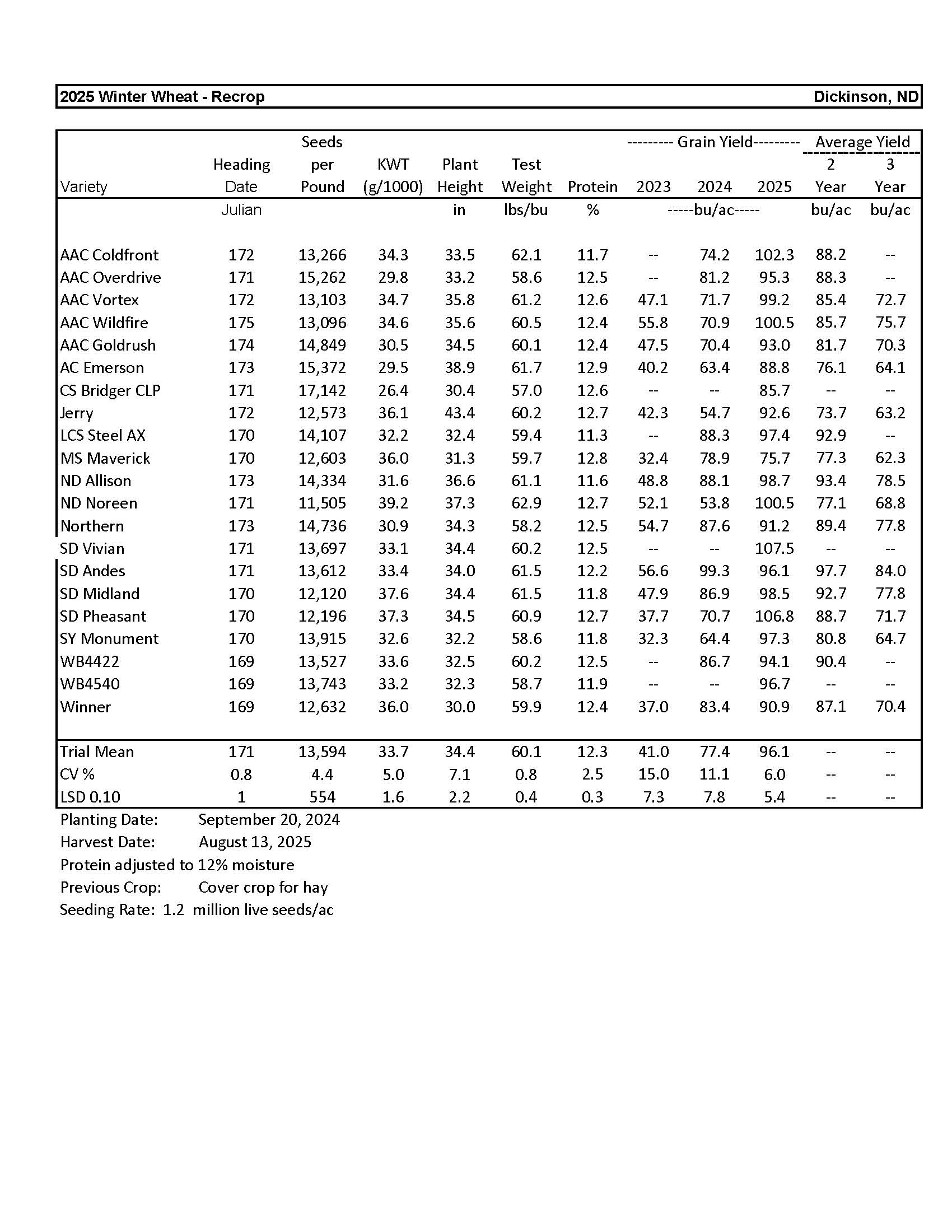

Winter Wheat........................................................................................................................ 5

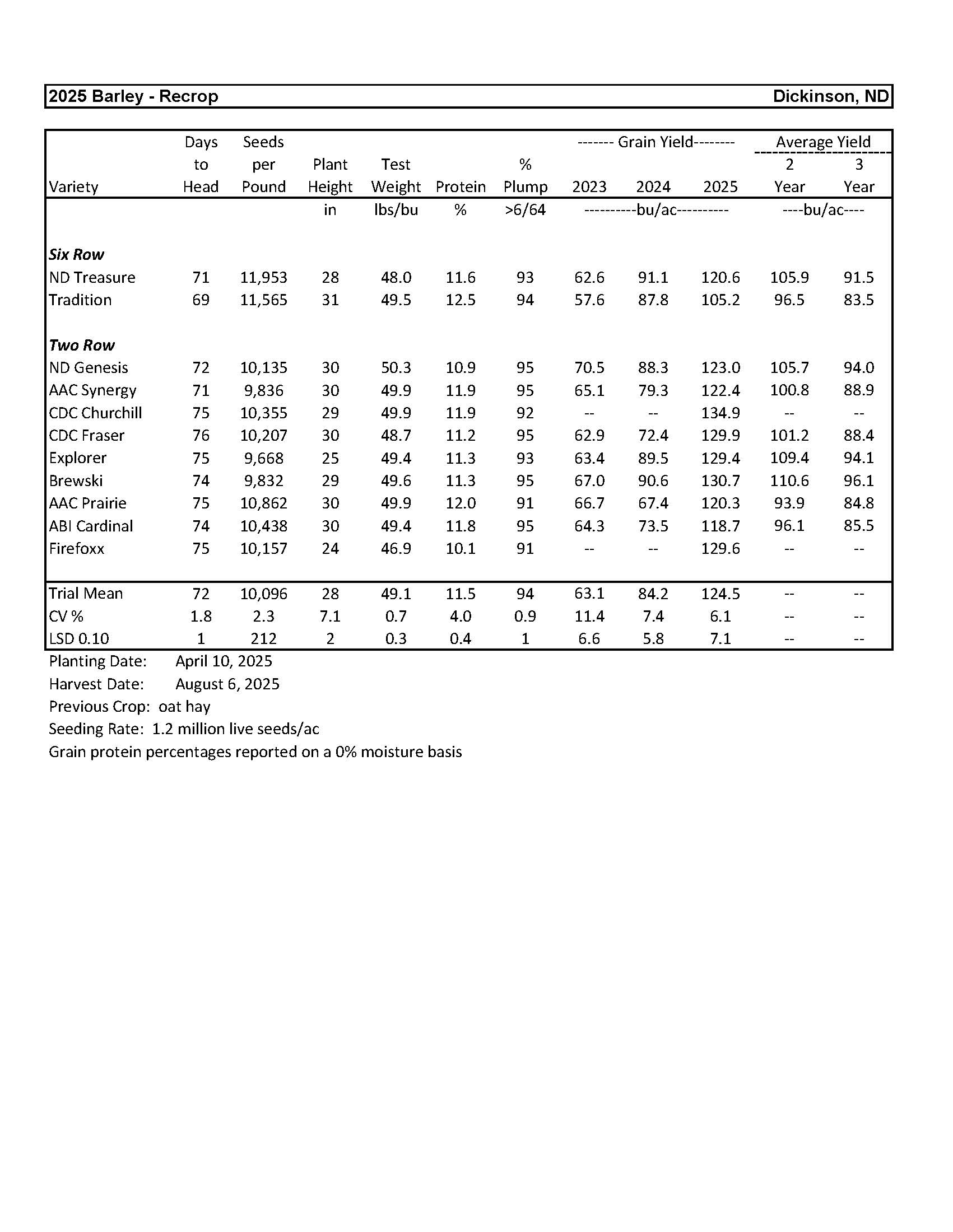

Barley................................................................................................................................... 6

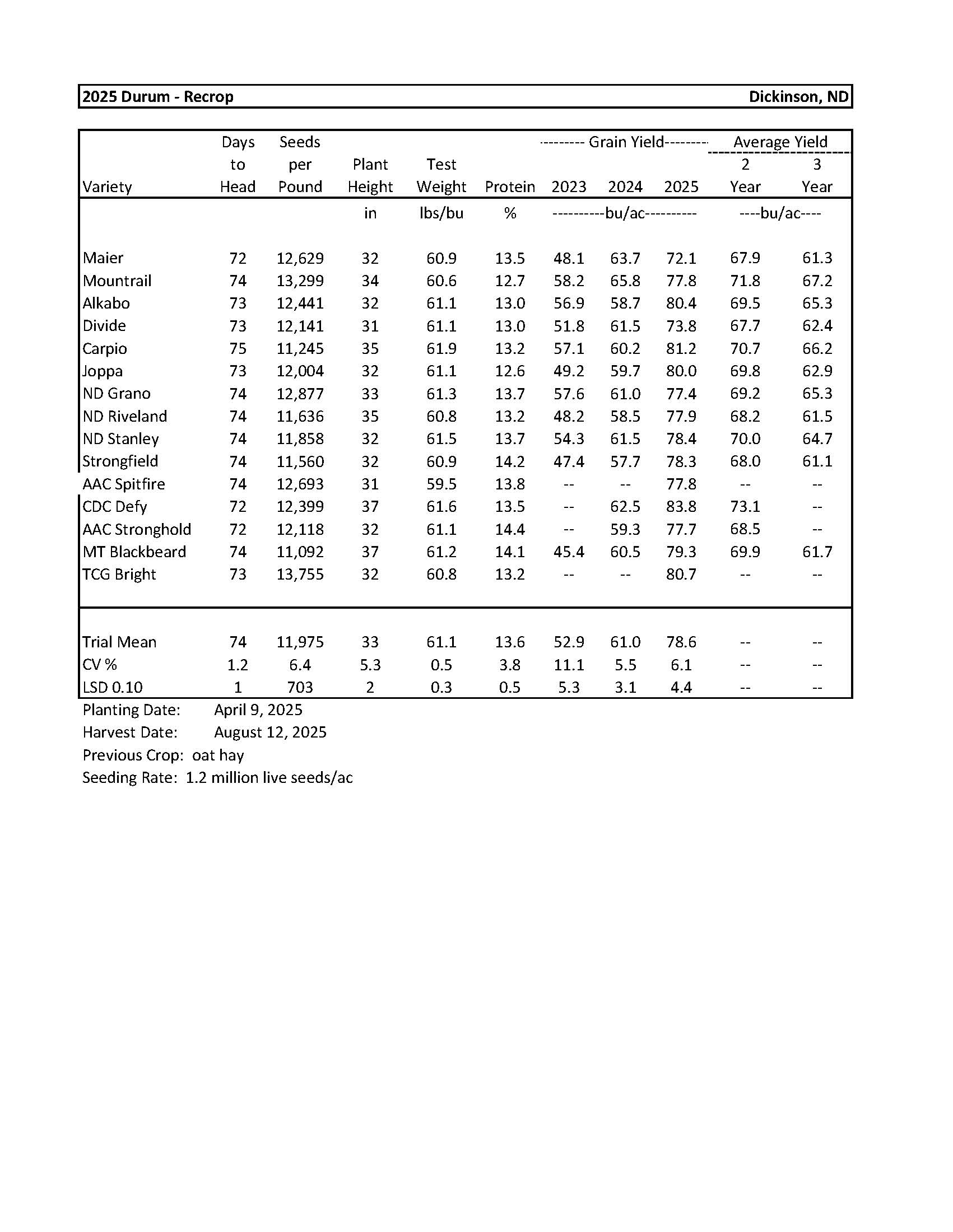

Durum................................................................................................................................... 7

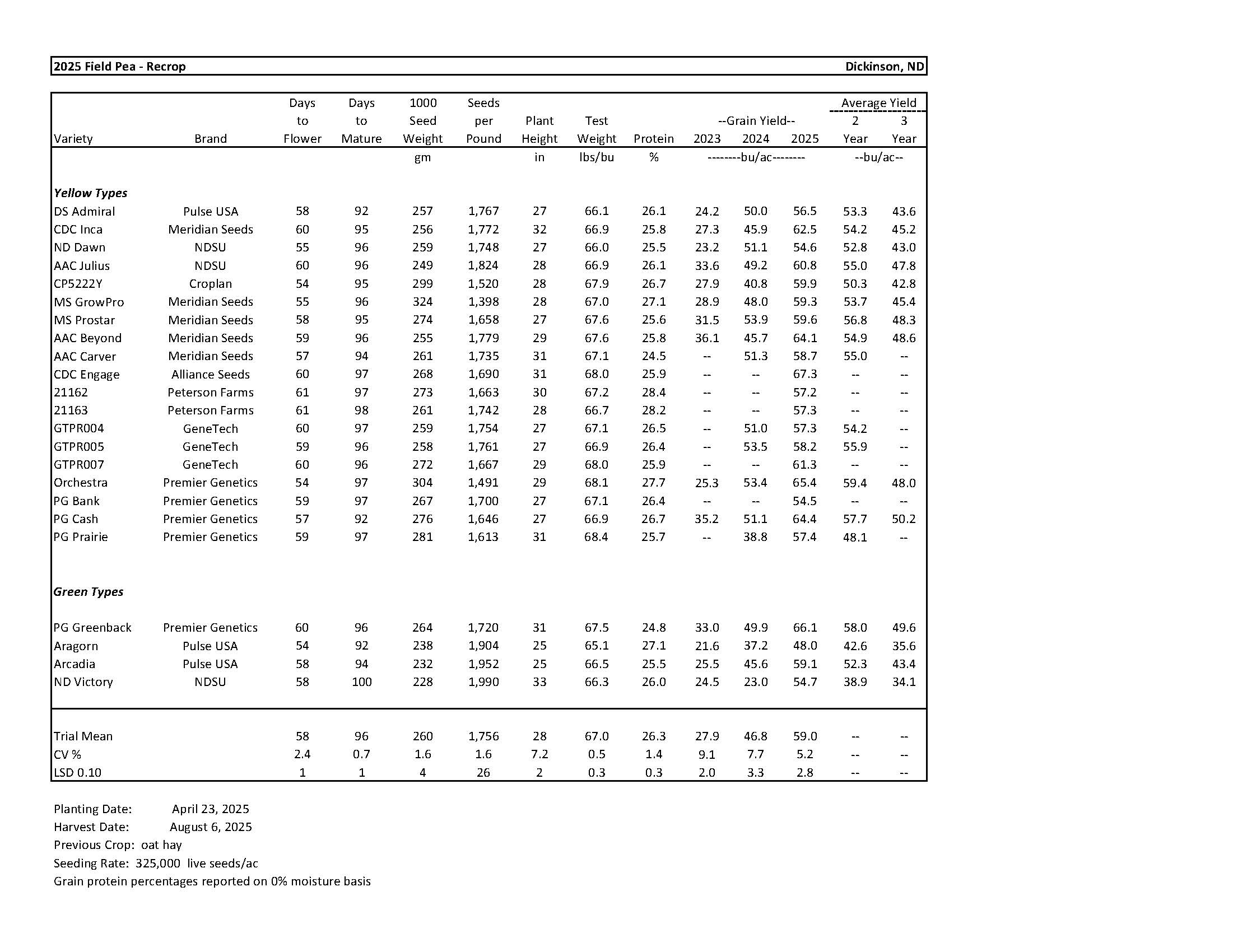

Field Pea............................................................................................................................... 8

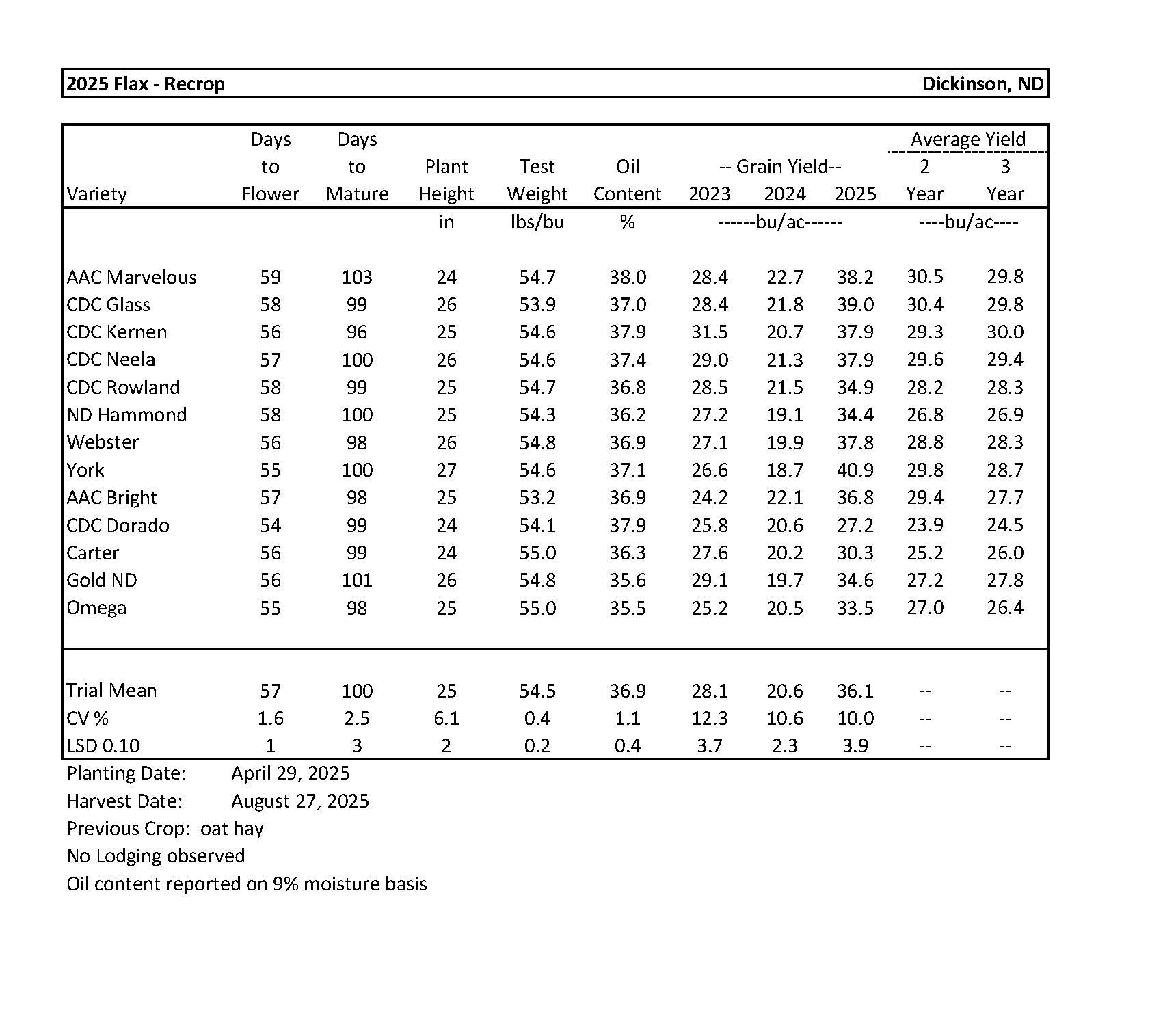

Flax....................................................................................................................................... 9

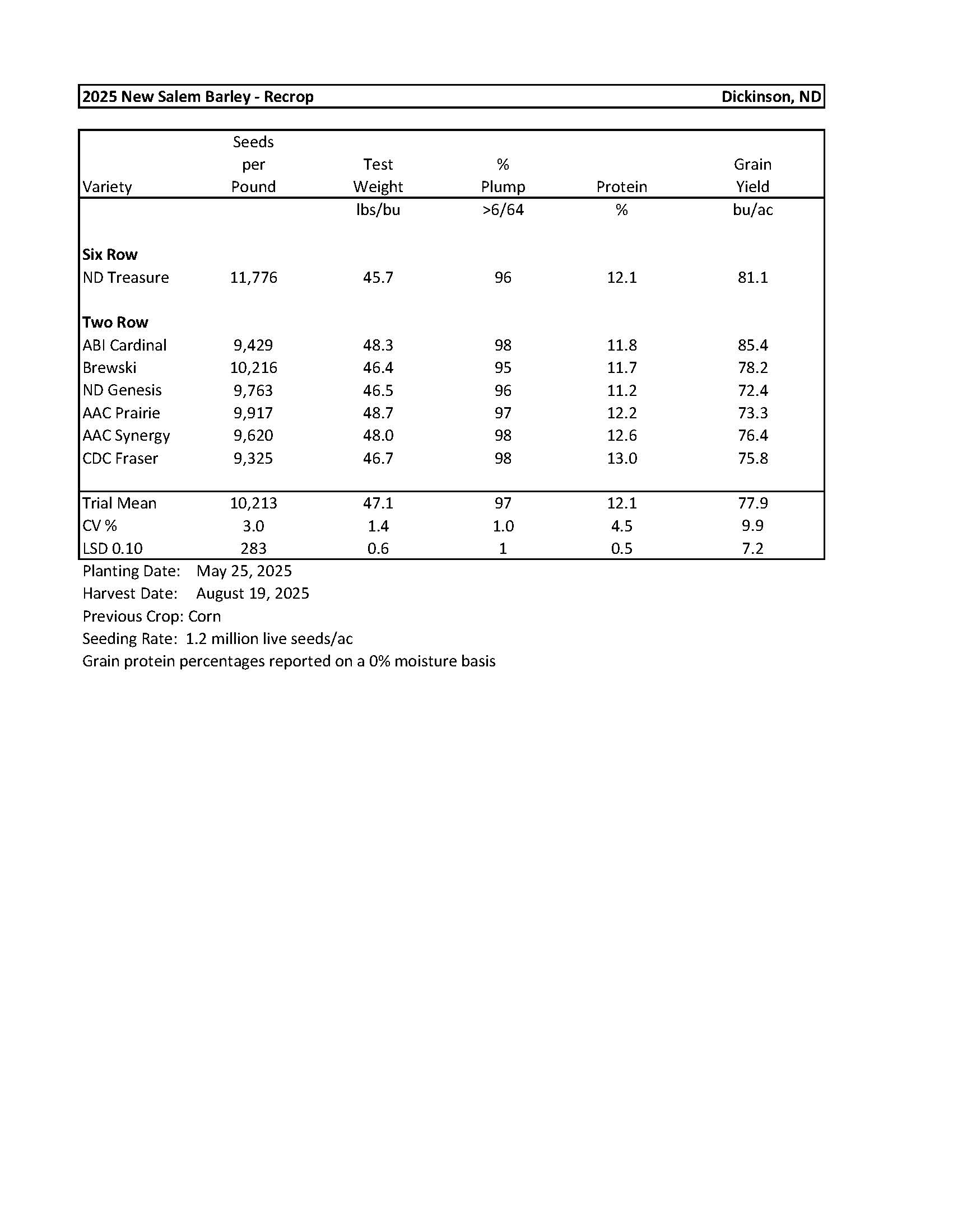

Barley-New Salem............................................................................................................... 10

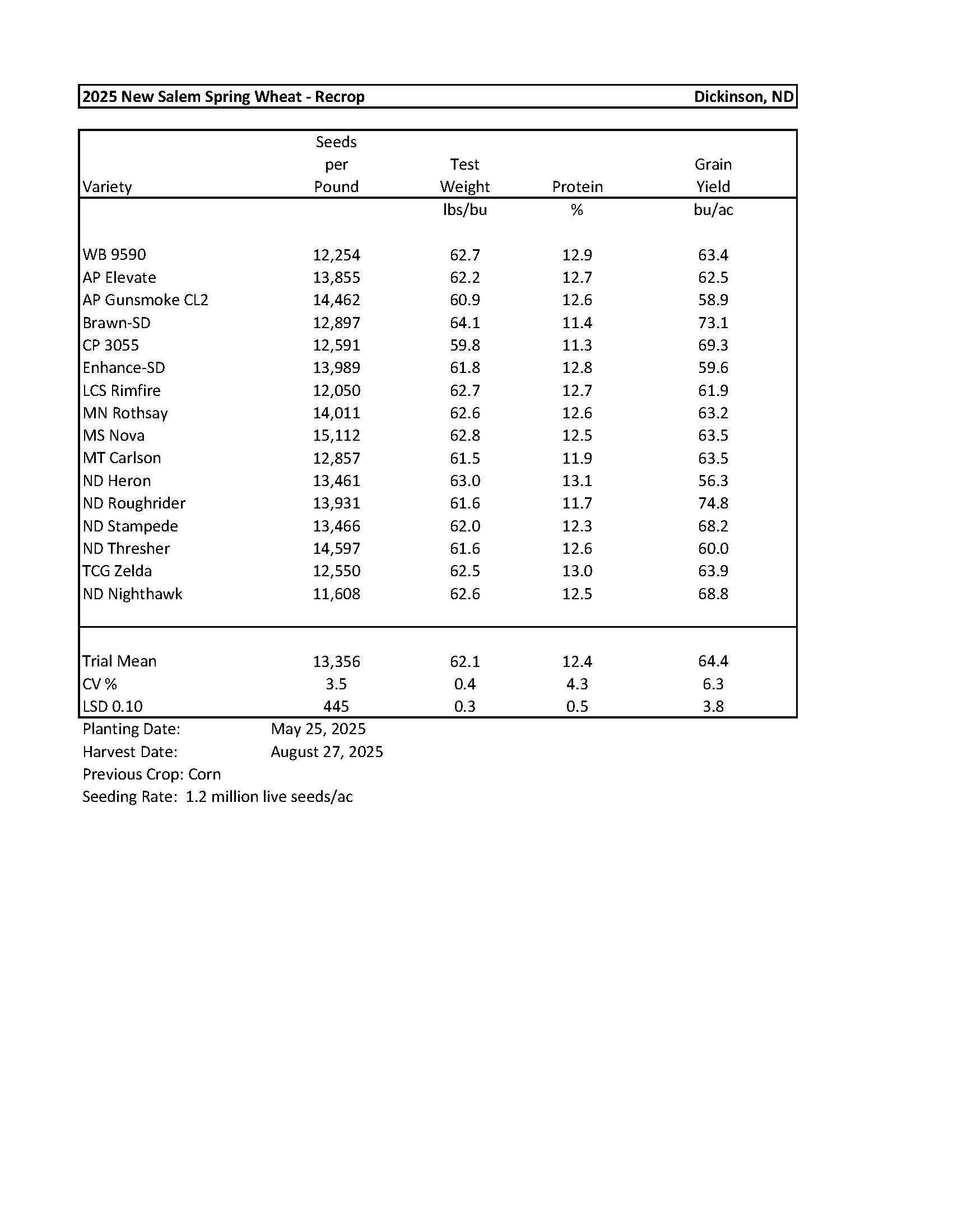

Spring Wheat-New Salem..................................................................................................... 11

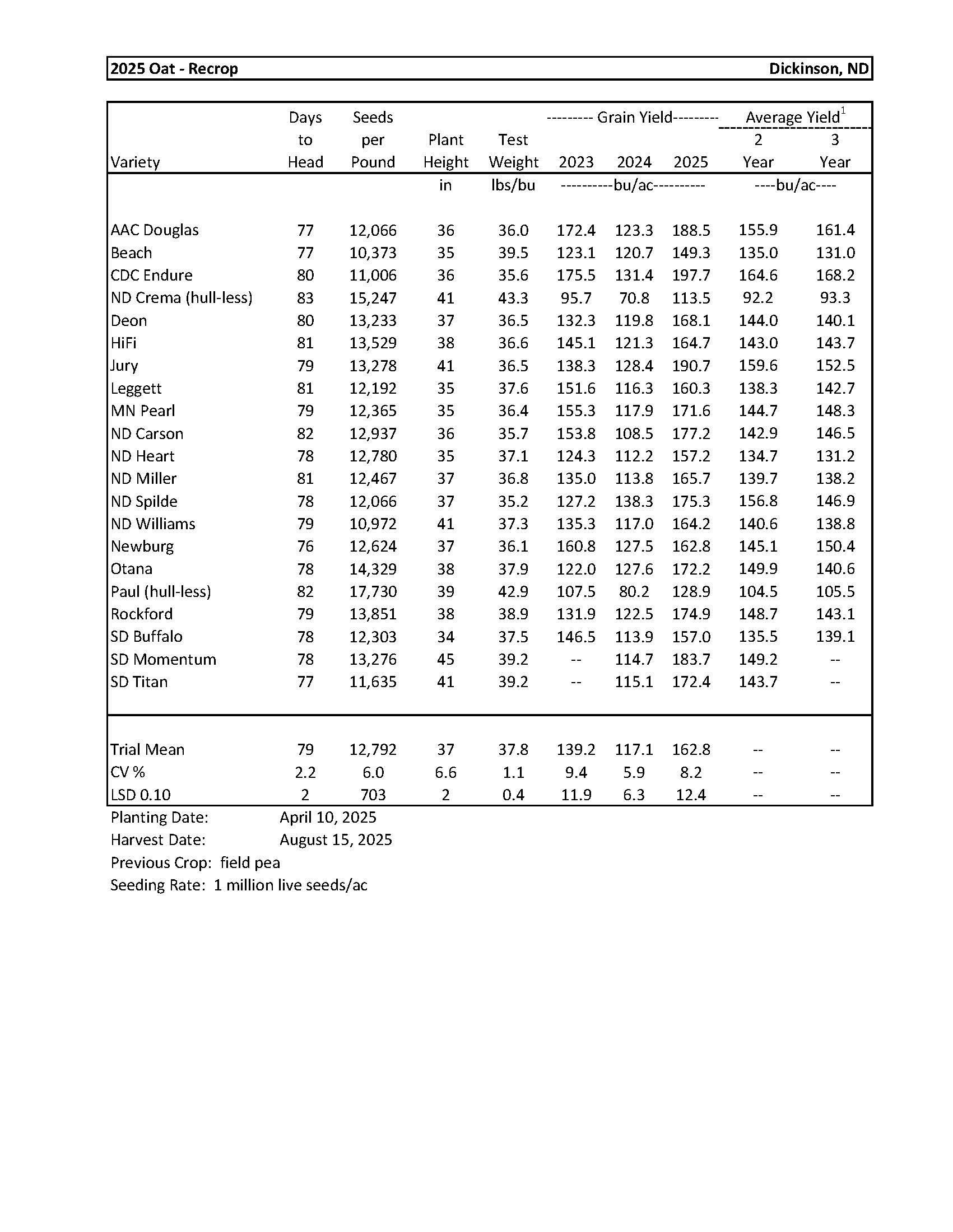

Oat...................................................................................................................................... 12

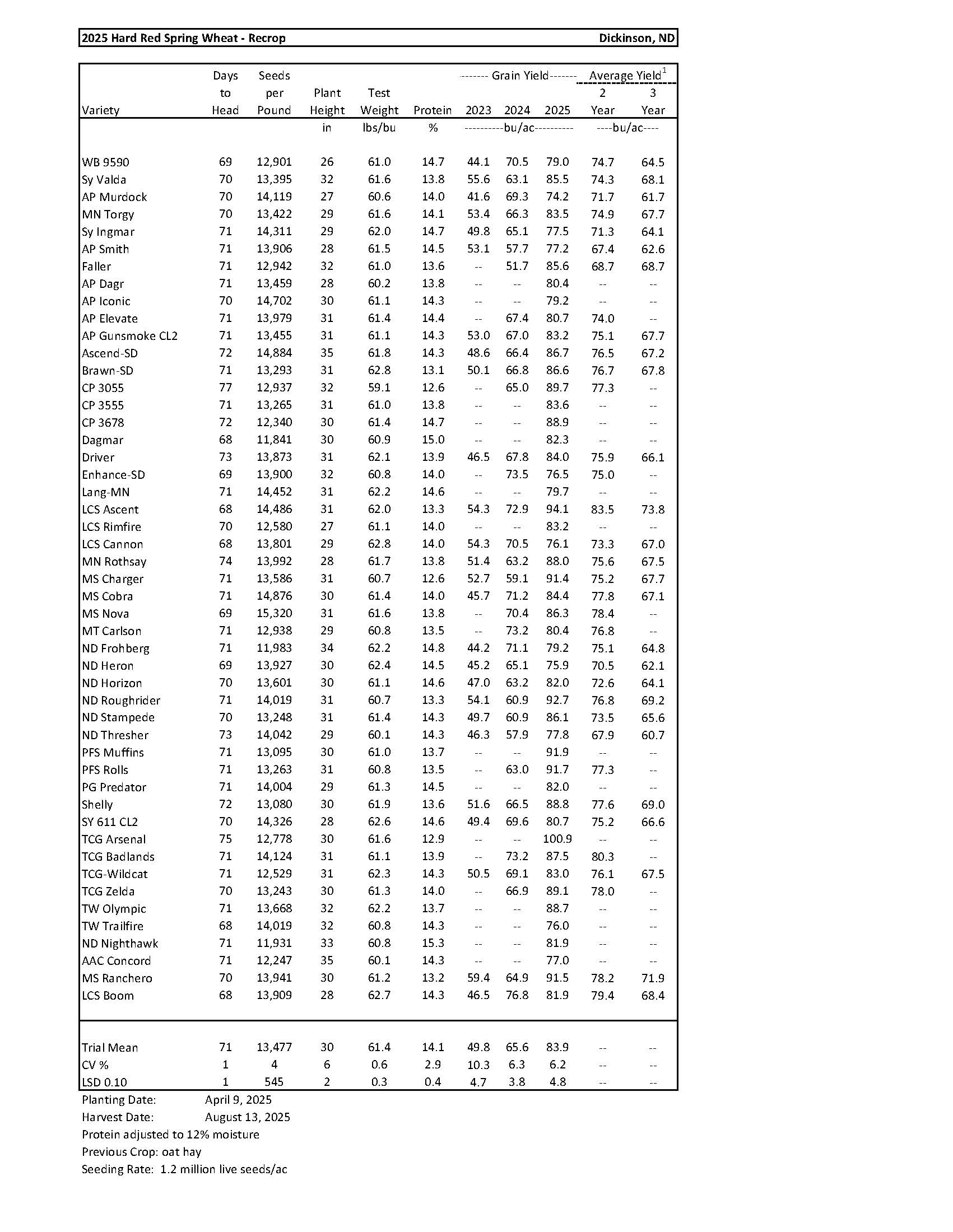

Hard Red Spring Wheat........................................................................................................ 13

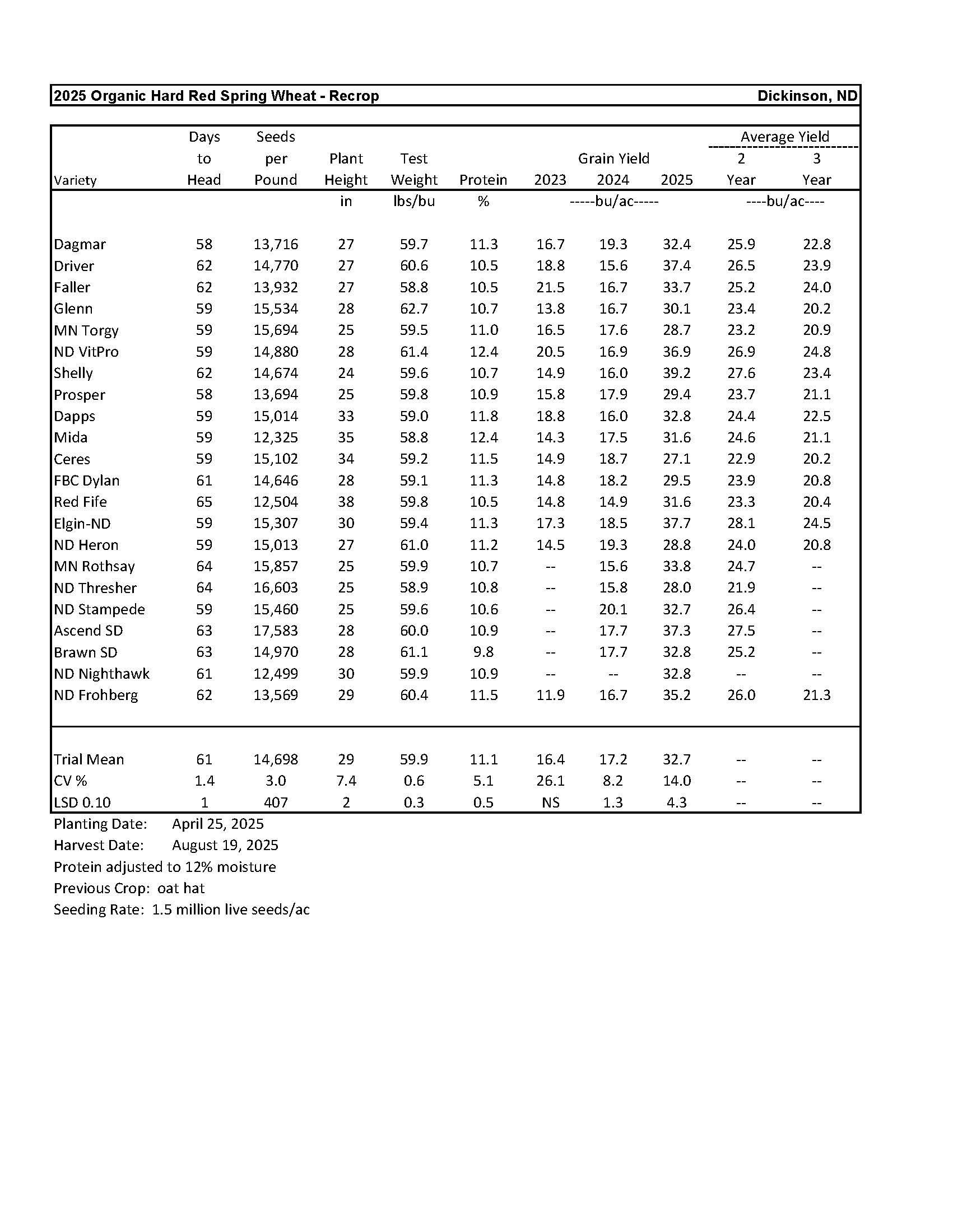

Organic Hard Red Spring Wheat........................................................................................... 14

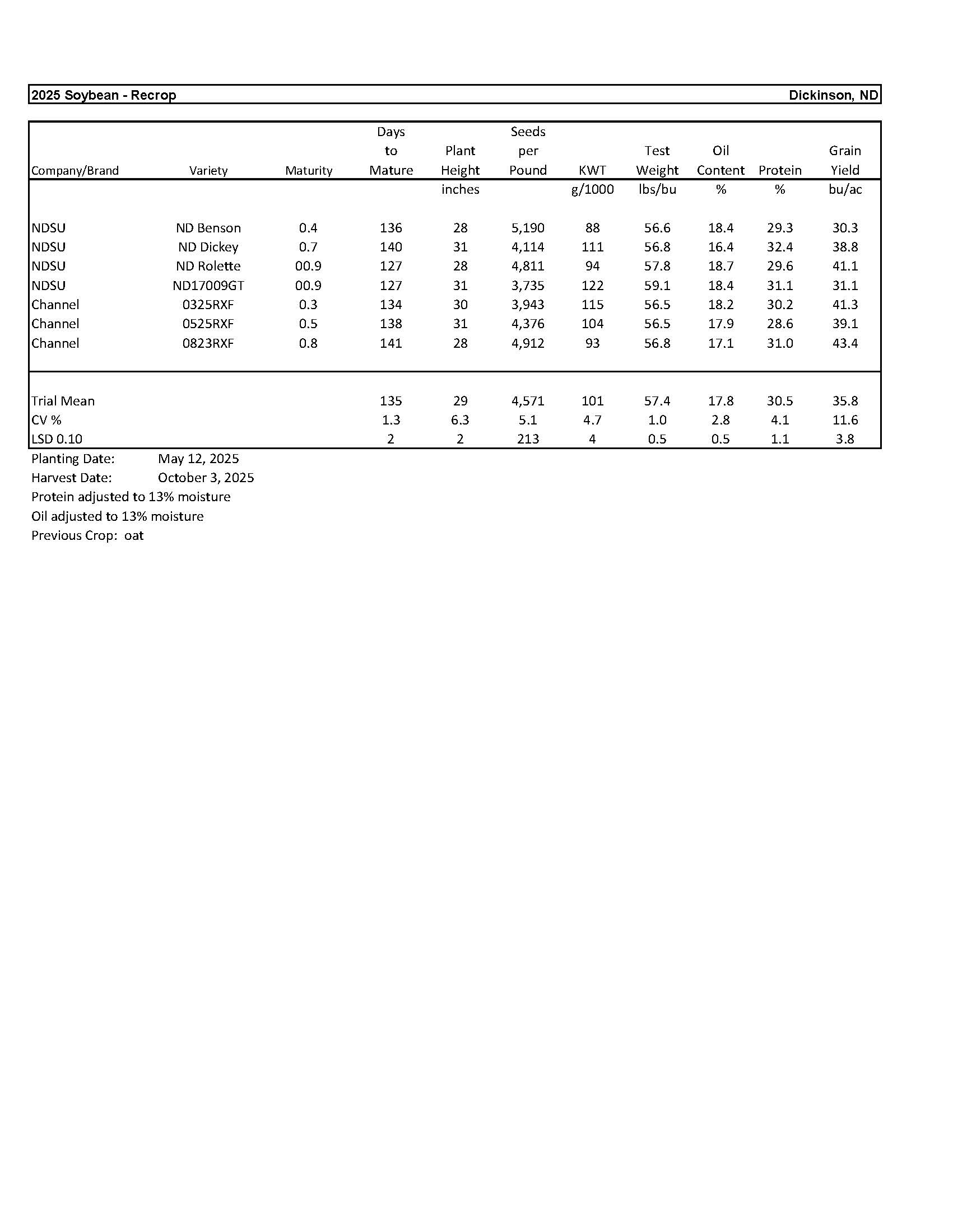

Soybean.............................................................................................................................. 15

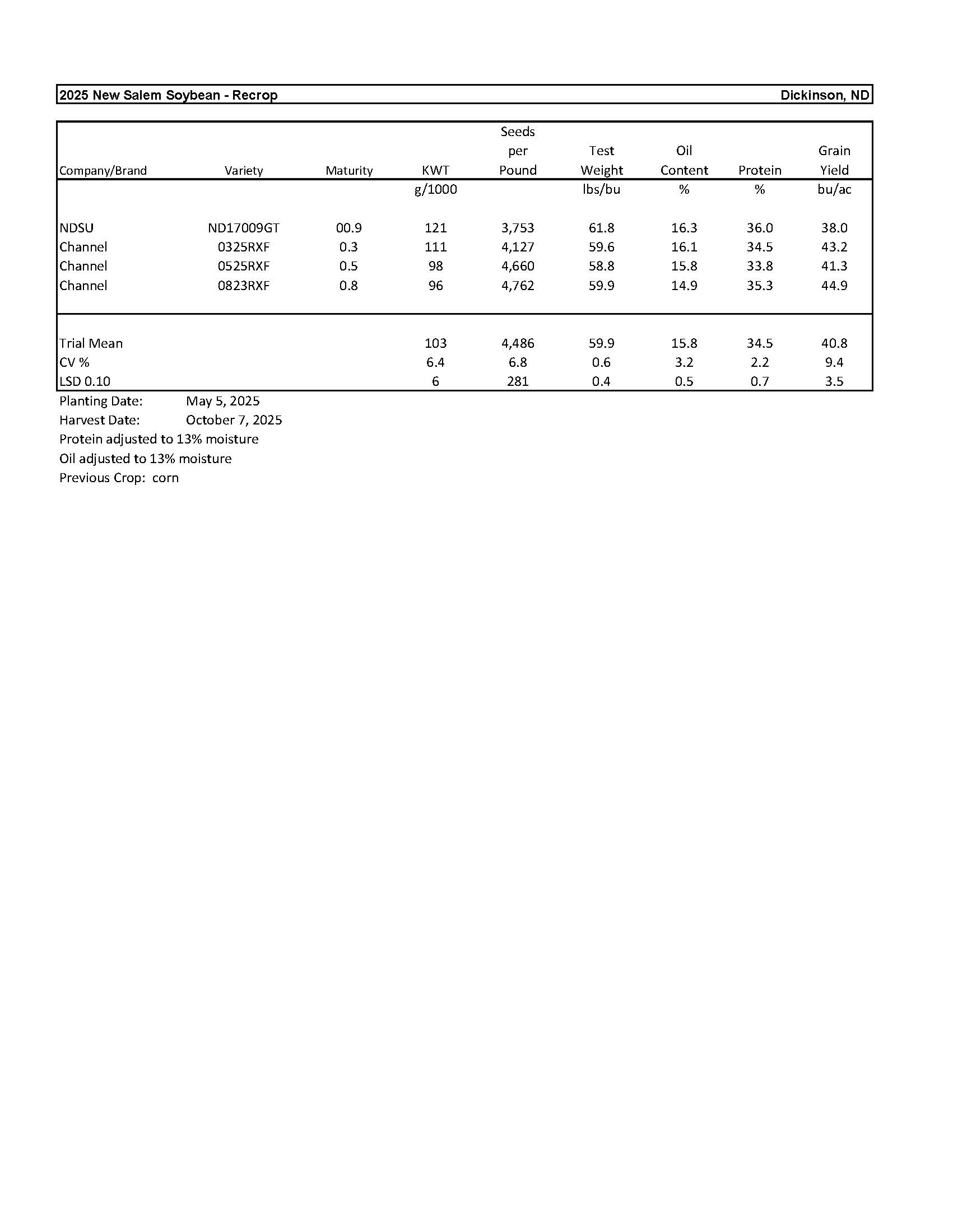

New Salem Soybean............................................................................................................. 16

Grassland Research

Restoration of Grassland Ecosystems to Full Functionality Requires Replacement

of Traditional Grazing Practices................................................................................... 17

Range Plant Growth Related to Climatic Factors of Western North Dakota, 1982-2024............ 23

Wildryes as Fall Complimentary Pastures for the Northern Plains........................................... 33

Agronomy Research

Determining Soybean Inoculation Strategies in Western North Dakota.................................... 44

Emergence and Early Growth of Hard Red Spring Wheat in Acid Soils of

Western North Dakota................................................................................................. 46

Boron Fertilization to Boost Canola Production in Western North Dakota................................ 53

Managing Soybean Inoculation in Western North Dakota Acidic Soils.................................... 58

Sulfur Fertilizer for Spring Canola Production in Western North Dakota.................................. 61

Sulfur Fertilizer for Spring Wheat Production in Western North Dakota-Year 3....................... 63

Soil Amendments and Inoculum to Improve Corn Production Under Soil Acidity and

No-Till Dryland System in Western North Dakota........................................................ 65

Lime Impacts on Spring Wheat Yield.................................................................................... 68

Sugarbeet Waste Lime Impacts on Field Pea Aphanomyces.................................................... 69

Livestock Research

Integrated Crop-Livestock System Research Publications: Past, Present, and Future................. 70

Drought Effects on Soil Microbial Activity, pH and Plant Nutrient Activity............................. 72

Extending the Breeding Season: Managing for Increased Profit............................................... 74

DREC Outreach

Outreach List 2025............................................................................................................... 75

Outreach Collaborators and Grants 2025................................................................................ 77

2025 Weekly Updates........................................................................................................... 78

Manning Weather Summary.................................................................................................. 80

Dickinson Weather Summary................................................................................................ 81

Pictures from Field Days 2025..............................................................................................82

2025 Variety Trials

Grassland Research

Restoration of Grassland Ecosystems to Full Functionality Requires Replacement of Traditional Grazing Practices

Llewellyn L. Manske PhD

Scientist of Rangeland Research

North Dakota State University

Dickinson Research Extension Center

Report DREC 25-1202

Traditional grazing practices used to manage Northern Plains grasslands cause serious problems that are so common that most people consider them to be inherent characteristics of the grasslands.

The three serious problems that every grassland managed by traditional grazing practices has are low quantities of available mineral nitrogen which causes the typical reduction of grass herbage production of 49.6% below the biological production level (Wight and Black 1972, 1979). Second year grass lead tillers drop below the nutrient requirements of modern high performance cattle around late July and livestock graze forage that is deficient of nutrients for the remainder of the grazing season. Traditionally managed cows produce milk below their biological potential and their calves gain weight at rates below their genetic potentials.

In order to correct these problems, we need to know both the basic science and the applied science of grassland ecosystems. During the period from early 1970’s through the 1990’s, numerous laboratory physiological scientists described the basic science of the grassland ecosystem biogeochemical processes performed by rhizosphere microbes, and the basic science of the internal grass plant growth mechanisms. These breakthrough scientific discoveries were not reported on the six o’clock news nor in the farm journals, so this important information is not widely known. Unfortunately, these basic physiological scientists did not do the necessary applied science field work to determine how to actually activate the rhizosphere microbes and all of the ecosystem processes and the grass growth mechanisms. That indispensable applied science research was conducted at the NDSU Dickinson REC by the rangeland research program scientist and assistants during the 1980’s and 1990’s.

Traditional grazing practices typically cause the quantity of mineral nitrogen to be available at 30 lbs to 60 lbs/ac, and long-term nongrazed treatments cause the amount of mineral nitrogen to drop to 10 lbs to 30 lbs/ac. In order for Northern Plains grasslands to produce grass herbage at biological potential, the grasslands must be grazed by large graminivores, and the available mineral nitrogen must be at the threshold quantity of 100 lbs/ac or greater (Wight and Black 1972).

Since the last climate change, that occurred around 5,000 years ago (Bluemle 2000) the Northern Plains grasslands have received by deposition at least 2 lbs of nitrogen per acre per year from the effects of the high temperatures of lightning. Nitrogen from lightning has resulted in a wide range of 3 to 8 tons of nitrogen per acre, with most intact grasslands containing 5 to 6 tons of nitrogen per acre (Brady 1974). However, this high amount of nitrogen is in the form of organic nitrogen, which is not available for plant use. Intact grassland soils do not require supplemental nitrogen to be added. Grassland soils require a greater biomass of rhizosphere microbes to transform organic nitrogen into mineral nitrogen (Manske 2018).

A limiting factor for increasing the biomass of rhizosphere microbes is that they do not possess chlorophyll and even if they had access to sunlight, soil microbes cannot capture their own carbon energy. The rhizosphere microbes require an outside source that can provide large quantities of short chain carbon energy before the microbes can increase in biomass. The small amount of carbohydrate leakage from grass plant roots is not enough energy, and the very low amount of 2% to 5% carbohydrate contained in dead grass material is not enough energy to greatly increase the biomass of soil microbes.

Fortunately, the outside source of short chain carbon energy for the soil microbes is conveniently located throughout the grassland. Grass lead tillers capture and fix large quantities of surplus carbohydrate energy during the vegetative growth stages occurring in the early portion of their second year of development. However, this surplus carbohydrate energy is not naturally released into the soil. Exudation of this surplus energy requires specific partial defoliation of lead tillers by large grazing graminivores that removes only 25% to 33% of the aboveground portion of the vegetative growth of grass lead tillers after the 3.5 new leaf stage and before the flower (anthesis) stage each growing season which will slowly release sizable proportions of the lead tiller surplus carbon energy through the roots into the microbial rhizosphere surrounding the grass roots (Manske 2018).

This extremely important outside source of short chain carbon energy will facilitate the rhizosphere microbes to greatly increase their biomass and then be able to transform organic nitrogen into mineral nitrogen, within about three growing seasons, the resulting rhizosphere microbe biomass will be large enough to transform mineral nitrogen at quantities at 100 lbs/ac or greater.

The rhizosphere microorganisms are responsible for the performance of all of the ecosystem nutrient flow activities and for the biogeochemical processes that determine grassland ecosystem productivity and functionality (Coleman et al. 1983).

- Biogeochemical processes transform stored essential elements from organic forms or ionic forms into plant usable mineral forms.

- Biogeochemical processes capture replacement quantities of lost or removed major essential elements of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen with assistance from active live plants and transform the replacement essential elements into storage as soil organic matter for later use.

- Biogeochemical processes decompose complex unusable organic material into compounds and then into reusable major and minor essential elements (Manske 2018).

The typical grassland problems of low grass herbage biomass production and the annual occurrence of nutrient quality deficiency of grass lead tiller forage after late July can be corrected with full activation of the four main internal grass plant growth mechanisms with partial defoliation by large grazing graminivores that remove 25% to 33% of the aboveground portion of the grass lead tillers at vegetative growth stages after the 3.5 new leaf stage and before the flower (anthesis) stage each growing season (Manske 2018).

The compensatory physiological grass growth mechanisms (McNaughton 1979, 1983, Briske 1991) give grass plants the capability to replace lost leaf and shoot biomass following partial grazing defoliation by increasing meristematic tissue activity, increasing photosynthetic capacity, inhibiting or reducing the rate of senescence, increasing the life span and leaf mass of remaining mature leaves, and increasing allocation of currently fixed carbon and available mineral nitrogen transformed by rhizosphere microbes. Fully activated growth mechanisms can produce replacement foliage at 140% of the herbage weight removed during grazing.

This increase in grass growth activity requires alternative sources of large quantities of carbon and nitrogen. Most of the nitrogen and carbon that was in the shoot is lost during partial defoliation. The preferential alternative source of nitrogen is the mineral nitrogen that has been converted from soil organic nitrogen by active rhizosphere microbes and available in the media around the roots. The alternative source of carbon is currently fixed by photosynthesis in remaining mature leaf and shoot tissue and rejuvenated portions of older leaves. The quantity of leaf area required to fix adequate quantities of carbon is 67% to 75% of the predefoliated leaf area (Manske 1999). Some of this currently fixed carbon is used to produce growth of replacement grass biomass and some of it is moved to the rhizosphere microbes for increased biomass and activity. Eventually, this carbon reaches the soil with an annual input rate of 2.5 tons C/ac.

The vegetative reproduction by tillering mechanisms (Mueller and Richards 1986, Richards et al. 1988, Murphy and Briske 1992, Briske and Richards 1994, 1995) develop secondary tiller shoots from growth of axillary buds on lead tillers. Meristematic activity in axillary buds and the subsequent development of vegetative secondary tillers is regulated by auxin, a growth-inhibiting hormone produced in the apical meristem and young developing leaves which prevents a growth hormone, cytokinin, from activation of the metabolic functions of the axillary buds. Partial defoliation by large grazing graminivores of young leaf material of grass lead tillers at vegetative growth stages temporarily reduces the production of the blockage hormone, auxin, which then allows the cytokinin synthesis or utilization in multiple axillary buds, stimulating the development of vegetative secondary tillers. Activation of secondary tillers from axillary buds on 60% to 80% of the grass lead tillers produce large quantities of vegetative tillers that have adequate nutrient quality that meet the requirements of modern beef cows from mid-July to mid-October each growing season. Vegetative tiller growth is the dominant form of grass reproduction in grasslands (Belsky 1992, Chapman and Peat 1992, Briske and Richards 1995, Chapman 1996, Manske 1999) not sexual reproduction and the development of seedlings. Recruitment of new grass plants developed from seedlings is negligible in healthy grassland ecosystems.

The precipitation water use efficiency mechanisms (Wight and Black 1972, 1979) are highly variable and do not function at an assumed fixed rate for each plant species. The factor that effects the rate of precipitation use efficiency is the quantity of available mineral nitrogen. When mineral nitrogen is available at the threshold quantity of 100 lbs/ac or greater, the grass precipitation use efficiency is fully engaged and highly effective resulting in increased grass herbage biomass production of 50.4% greater per inch of precipitation received than in grasslands with mineral nitrogen available at less than 100 lbs/ac. The efficiency of precipitation use in grass plants function at extremely low levels when mineral nitrogen is deficient below the threshold quantity of 100 lbs/ac. The level of precipitation water use efficiency determines the quantity of grass herbage biomass productivity on grassland ecosystems.

The nutrient resource uptake mechanisms (Crider 1955, Whitman 1974, Li and Wilson 1998, Kochy and Wilson 2000, Peltzer and Kochy 2001) regulate grass plant competitiveness at nutrient and soil water resource uptake and determine the relative dominance of grass plants within a grassland community. Healthy vigorous grass plants have a high nutrient resource uptake efficiency and are superior competitors for mineral nitrogen and soil water and are able to suppress the expansion of shrub rhizomes and prevent successful establishment of invasive shrubs, weedy forbs, and undesirable grass seedlings into the grasslands. However, the use of degrading traditional management practices and the removal of 50% or more of the grass plant aboveground leaf material cause reduced root growth, root respiration, and root nutrient absorption resulting in a reduction of functionality of the grass plants, a diminishment of grass plant health and vigor, a loss of resource uptake efficiency, and a suppression of the competitiveness of grass plants to take up mineral nitrogen, essential elements, and soil water. Undesirable shrub, forb, and grass plants are able to become established within the degraded grass community and then able to uptake the belowground resources no longer consumed by the smaller, less vigorous, deteriorated grass plants, and proportionally increase the undesirable plant biomass production and increase their occupied space in the deteriorated grassland community. Traditionally, the observation of increases of undesirable trees, shrubs, forbs, and grasses into degraded grassland ecosystems would have been explained as a result of fire suppression (Humphrey 1962, Stoddart Smith, and Box 1975, Wright and Bailey 1982) rather than the actual physiological reduction of the grass plant nutrient resource uptake mechanisms.

We now have access to the basic science reports on how the ecosystem biogeochemical processes and the four main grass growth mechanisms work. We know how to increase the biomass of the rhizosphere microbes. We have knowledge from the applied science work on how and when we can activate the biogeochemical processes and the four main grass growth mechanisms to function properly. With the accumulation of all this scientific information, we can replace the detrimental traditional management practices, and develop and establish a biologically effective strategy for proper ecological management of the grasslands of the Northern Plains.

The biologically effective twice-over rotation strategy is designed to coordinate partial defoliation events of large grazing graminivores with grass phenological growth stages, in order to meet the nutrient requirements of the graminivores, the biological requirements of the grass plants and the rhizosphere microbes, to enhance the ecosystem biogeochemical processes, and to activate the four main internal grass plant growth mechanisms for the biologically effective facilitation of grassland ecosystems to full functionality at the greatest achievable levels.

The twice-over rotation grazing strategy uses three to six native grassland pastures. Each pasture is grazed for two periods per growing season. The number of grazing periods is determined by the number of sets of tillers: one set of lead tillers and one set of vegetation secondary tillers per growing season. The first grazing period is 45 days long, ideally, from 1 June to 15 July, with each pasture grazed for 7 to 17 days (never less or more). The number of days of the first grazing period on each pasture is the same percentage of 45 days as the percentage of the total season’s grazeable forage contributed by each pasture to the complete system. The forage is measured as animal unit months (AUM’s). The average grazing season month is 30.5 days long (Manske 2012). The number of days grazed are not counted by calendar dates, but by the number of 24-hr periods grazed from the date and time the livestock are turned out to pasture. The second grazing period is 90 days long, ideally from 15 July to 14 October, each pasture is grazed for twice the number of days as in the first period. The length of the total summer grazing period is best at 135 days; 45 days during the first period plus 90 days during the second period (Manske 2018).

During the first period, partial defoliation that removes 25% to 33% of the leaf biomass from grass lead tillers between the 3.5 new leaf stage and the flower stage increases the rhizosphere microbe biomass and activity, enhances the ecosystem biogeochemical processes, and activates the four main internal grass plant growth mechanisms. Manipulation of these processes and mechanisms does not occur at any other time during the growing season. During the second grazing period, the lead tillers are maturing and declining in nutritional quality, and partial defoliation can remove up to 50% of the leaf biomass. Adequate forage nutritional quality during the second period depends on the activation of the vegetative tillering mechanisms with sufficient quantities of vegetative secondary tiller growth from axillary buds during the first period. Livestock must be removed from intact native grassland pastures in mid October, towards the end of the perennial grass growing season, in order to allow the carryover tillers to store the carbohydrates and nutrients which will maintain plant life functions over the winter. Most of the upright vegetative tillers on grassland ecosystems during the autumn will be carryover tillers which will resume growth as lead tillers during the next growing season. Almost all grass tillers live for two growing seasons, the first season as vegetative secondary tillers, and the second season as lead tillers. Grazing carryover tillers after mid October causes the termination of a large proportion of the grass population, resulting in greatly reduced herbage biomass production in subsequent growing seasons. The pasture grazed first in the rotation sequence is the last pasture grazed during the previous year; i.e. ABC, CAB, and BCA, because the last pasture grazed has the greatest green live herbage weight on 1 June of the start of the following grazing season (Manske 2018).

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to Sheri Schneider for assistance in production of this manuscript.

Literature Cited

Belsky, A.J. 1992. Effects of grazing competition, disturbance and fire on species composition and diversity in grassland communities. Journal of Vegetation Science 3:187-200.

Bluemle, J.P. 2000. The face of North Dakota. 3rd edition. North Dakota Geological Survey. Ed. Series 26. 206p. 1pl.

Brady, N.C. 1974. The nature and properties of soils. MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., New York, NY. 639p.

Briske, D.D. 1991. Developmental morphology and physiology of grasses. p. 85-108. in R.K. Heitschmidt and J.W. Stuth (eds.). Grazing management: an ecological perspective. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

Briske, D.D., and J.H. Richards. 1994. Physiological responses of individual plants to grazing: current status and ecological significance. p. 147-176. in M. Vavra, W.A. Laycock, and R.D. Pieper (eds.). Ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the west. Society for Range Management, Denver, CO.

Briske, D.D., and J.H. Richards. 1995. Plant response to defoliation: a physiological, morphological, and demographic evaluation. p. 635-710. in D.J. Bedunah and R.E. Sosebee (eds.). Wildland plants: physiological ecology and developmental morphology. Society for Range Management, Denver, CO.

Chapman, G.P., and W.E. Peat. 1992. An introduction to the grasses. C.A.B. International, Wallingford, UK. 111p.

Chapman, G.P. 1996. The biology of grasses. C.A.B. International, Wallingford, UK. 273p.

Coleman, D.C., C.P.P. Reid, and C.V. Cole. 1983. Biological strategies of nutrient cycling in soil ecosystems. Advances in Ecological Research 13:1-55.

Crider, F.J. 1955. Root-growth stoppage resulting from defoliation of grass. USDA Technical Bulletin 1102. 23p.

Humphrey, R.R. 1962. Range Ecology. The Ronald Press Co. New York, NY. 234p.

Kochy, M., and S.D. Wilson. 2000. Competitive effects of shrubs and grasses in prairie. Oikos 91:385-395.

Li, X., and S.D. Wilson. 1998. Facilitation among woody plants establishing in an old field. Ecology 79:2694-2705.

Manske, L.L. 1999. Can native prairie be sustained under livestock grazing? Provincial Museum of Alberta. Natural History Occasional Paper No. 24. Edmonton, AB. p. 99-108.

Manske, L.L. 2012. Length of the average grazing season month. NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center. Range Management Report DREC 12-1021c. Dickinson, ND. 2p.

Manske, L.L. 2018. Restoring degraded grasslands. pp. 325-351. in A. Marshall and R. Collins (ed.). Improving grassland and pasture management in temperate agriculture. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, Cambridge, UK.

McNaughton, S.J. 1979. Grazing as an optimization process: grass-ungulate relationships in the Serengeti. American Naturalist 113:691-703.

McNaughton, S.J. 1983. Compensatory plant growth as a response to herbivory. Oikos 40:329-336.

Mueller, R.J., and J.H. Richards. 1986. Morphological analysis of tillering in Agropyron spicatum and Agropyron desertorum. Annals of Botany 58:911-921.

Murphy, J.S., and D.D. Briske. 1992. Regulation of tillering by apical dominance: chronology, interpretive value, and current perspectives. Journal of Range Management 45:419-429.

Peltzer, D.A., and M. Kochy. 2001. Competitive effects of grasses and woody plants in mixed grass prairie. Journal of Ecology 89:519-527.

Richards, J.H., R.J. Mueller, and J.J. Mott. 1988. Tillering in tussock grasses in relation to defoliation and apical bud removal. Annals of Botany 62:173-179.

Stoddart, L.A., A.D. Smith, and T.W. Box. 1975. Range Management. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Book Co. New York, NY. 532p.

Whitman, W.C. 1974. Influence of grazing on the microclimate of mixed grass prairie. p. 207-218. in Plant Morphogenesis as the basis for scientific management of range resources. USDA Miscellaneous Publication 1271.

Wight, J.R., and A.L. Black. 1972. Energy fixation and precipitation use efficiency in a fertilized rangeland ecosystem of the Northern Great Plains. Journal of Range Management 25:376-380.

Wight, J.R., and A.L. Black. 1979. Range fertilization: plant response and water use. Journal of Range Management 32:345-349.

Wright, H.A., and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Fire Ecology: United States and southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons. New York, NY. 501p.

Range Plant Growth Related to Climatic Factors

of Western North Dakota, 1982-2024.

Llewellyn L. Manske PhD

Scientist of Rangeland Research

North Dakota State University

Dickinson Research Extension Center

Report DREC 25-1078n

Introduction

Successful long-term management of grassland ecosystems requires knowledge of the relationships of range plant growth and regional climatic factors. Range plant growth and development are regulated by climatic conditions. Length of daylight, temperature, precipitation, and water deficiency are the most important climatic factors that affect rangeland plants (Manske 2011).

Light

Light is necessary for plant growth because light is the source of energy for photosynthesis. Plant growth is affected by variations in quality, intensity, and duration of light. The quality of light (wavelength) varies from region to region, but the quality of sunlight does not vary enough in a given region to have an important differential effect on the rate of photosynthesis. However, the intensity (measurable energy) and duration (length of day) of sunlight change with the seasons and affect plant growth. Light intensity varies greatly with the season and with the time of day because of changes in the angle of incidence of the sun’s rays and the distance light travels through the atmosphere. Light intensity also varies with the amount of humidity and cloud cover because atmospheric moisture absorbs and scatters light rays.

The greatest variation in intensity of light received by range plants results from the various degrees of shading from other plants. Most range plants require full sunlight or very high levels of sunlight for best growth. Shading from other plants reduces the intensity of light that reaches the lower leaves of an individual plant. Grass leaves grown under shaded conditions become longer but narrower, thinner (Langer 1972, Weier et al. 1974), and lower in weight than leaves in sunlight (Langer 1972). Shaded leaves have a reduced rate of photosynthesis, which decreases the carbohydrate supply and causes a reduction in growth rate of leaves and roots (Langer 1972). Shading increases the rate of senescence in lower, older leaves. Accumulation of standing dead leaves ties up carbon and nitrogen. Decomposition of leaf material through microbial activity can take place only after the leaves have made contact with the soil. Standing dead material not in contact with the soil does not decompose but breaks down slowly as a result of leaching and weathering. Under ungrazed treatments the dead leaves remain standing for several years, slowing nutrient cycles, restricting nutrient supply, and reducing soil microorganism activity in the top 12 inches of soil. Standing dead leaves shade early leaf growth in spring and therefore slow the rate of growth and reduce leaf area. Long-term effects of shading, such as that occurring in ungrazed grasslands and under shrubs or leafy spurge, reduce the native grass species composition and increase composition of shade-tolerant or shade- adapted replacement species like smooth bromegrass and Kentucky bluegrass.

Day-length period (photoperiod) is one of the most dependable cues by which plants time their activities in temperate zones. Day-length period for a given date and locality remains the same from year to year. Changes in the photoperiod function as the timer or trigger that activates or stops physiological processes bringing about growth and flowering of plants and that starts the process of hardening for resistance to low temperatures in fall and winter. Sensory receptors, specially pigmented areas in the buds or leaves of a plant, detect day length and night length and can activate one or more hormone and enzyme systems that bring about physiological responses (Odum 1971, Daubenmire 1974, Barbour et al. 1987).

The phenological development of rangeland plants is triggered by changes in the length of daylight. Vegetative growth is triggered by photoperiod and temperature (Langer 1972, Dahl 1995), and reproductive initiation is triggered primarily by photoperiod (Roberts 1939, Langer 1972, Leopold and Kriedemann 1975, Dahl 1995) but can be slightly modified by temperature and precipitation (McMillan 1957, Leopold and Kriedemann 1975, Dahl and Hyder 1977, Dahl 1995). Some plants are long-day plants and others are short-day plants. Long-day plants reach the flower phenological stage after exposure to a critical photoperiod and during the period of increasing daylight between mid April and mid-June. Generally, most cool-season plants with the C3 photosynthetic pathway are long-day plants and reach flower phenophase before 21 June. Short-day plants are induced into flowering by day lengths that are shorter than a critical length and that occur during the period of decreasing day length after mid-June. Short-day plants are technically responding to the increase in the length of the night period rather than to the decrease in the day length (Weier et al. 1974, Leopold and Kriedemann 1975). Generally, most warm-season plants with the C4 photosynthetic pathway are short-day plants and reach flower phenophase after 21 June.

The annual pattern in the change in daylight duration follows the seasons and is the same every year for each region. Grassland management strategies based on phenological growth stages of the major grasses can be planned by calendar date after the relationships between phenological stage of growth of the major grasses and time of season have been determined for a region.

Temperature

Temperature is an approximate measurement of the heat energy available from solar radiation. At both low and high levels temperature limits plant growth. Most plant biological activity and growth occur within only a narrow range of temperatures, between 32o F (0o C) and 122o F (50o C) (Coyne et al. 1995). Low temperatures limit biological reactions because water becomes unavailable when it is frozen and because levels of available energy are inadequate. However, respiration and photosynthesis can continue slowly at temperatures well below 32o F if plants are “hardened”. High temperatures limit biological reactions because the complex structures of proteins are disrupted or denatured.

Periods with temperatures within the range for optimum plant growth are very limited in western North Dakota. The frost-free period is the number of days between the last day with minimum temperatures below 32o F (0o C) in the spring and the first day with minimum temperatures below 32o F (0o C) in the fall and is approximately the length of the growing season for annually seeded plants. The frost-free period for western North Dakota generally lasts for 120 to 130 days, from mid to late May to mid to late September (Ramirez 1972). Perennial grassland plants are capable of growing for periods longer than the frost-free period, but to continue active growth they require temperatures above the level that freezes water in plant tissue and soil. Many perennial plants begin active growth more than 30 days before the last frost in spring and continue growth after the first frost in fall. The growing season for perennial plants is considered to be between the first 5 consecutive days in spring and the last 5 consecutive days in fall with mean daily temperature at or above 32o F (0o C). In western North Dakota the growing season for perennial plants is considered to be generally from mid April through mid October. Low air temperature during the early and late portions of the growing season greatly limits plant growth rate. High temperatures, high evaporation rates, drying winds, and low precipitation levels after mid summer also limit plant growth.

Different plant species have different optimum temperature ranges. Cool-season plants, which are C3 photosynthetic pathway plants, have an optimum temperature range of 50o to 77o F (10o to 25o C). Warm-season plants, which are C4 photosynthetic pathway plants, have an optimum temperature range of 86o to 105o F (30o to 40o C) (Coyne et al. 1995).

Water (Precipitation)

Water, an integral part of living systems, is ecologically important because it is a major force in shaping climatic patterns and biochemically important because it is a necessary component in physiological processes (Brown 1995). Water is the principal constituent of plant cells, usually composing over 80% of the fresh weight of herbaceous plants. Water is the primary solvent in physiological processes by which gases, minerals, and other materials enter plant cells and by which these materials are translocated to various parts of the plant. Water is the substance in which processes such as photosynthesis and other biochemical reactions occur and a structural component of proteins and nucleic acids. Water is also essential for the maintenance of the rigidity of plant tissue and for cell enlargement and growth in plants (Brown 1977, Brown 1995).

Water Deficiency

Temperature and precipitation act together to affect the physiological and ecological status of range plants. The biological situation of a plant at any time is determined by the balance between rainfall and potential evapotranspiration. The higher the temperature, the greater the rate of evapotranspiration and the greater the need for rainfall to maintain homeostasis. When the amount of rainfall received is less than potential evapotranspiration demand, a water deficiency exists. Evapotranspiration demand is greater than precipitation in the mixed grass and short grass prairie regions. The tall grass prairie region has greater precipitation than evapotranspiration demand. Under water deficiency conditions, plants are unable to absorb adequate water to match the transpiration rate, and plant water stress develops. Range plants have mechanisms that help reduce the damage from water stress, but some degree of reduction in herbage production occurs.

Plant water stress limits growth. Plant water stress develops in plant tissue when the rate of water loss through transpiration exceeds the rate of water absorption by the roots. Water stress can vary in degree from a small decrease in water potential, as in midday wilting on warm, clear days, to the lethal limit of desiccation (Brown 1995).

Early stages of water stress slow shoot and leaf growth. Leaves show signs of wilting, folding, and discoloration. Tillering and new shoot development decrease. Root production may increase. Senescence of older leaves accelerates. Rates of cell wall formation, cell division, and protein synthesis decrease. As water stress increases, enzyme activity declines and the formation of necessary compounds slows or ceases. The stomata begin to close; this reaction results in decreased rates of transpiration and photosynthesis. Rates of respiration and translocation decrease substantially with increases in water stress. When water stress becomes severe, most functions nearly or completely cease and serious damage occurs. Leaf and root mortality induced by water stress progresses from the tips to the crown. The rate of leaf and root mortality increases with increasing stress. Water stress can increase to a point that is lethal, resulting in damage from which the plant cannot recover. Plant death occurs when meristems become so dehydrated that cells cannot maintain cell turgidity and biochemical activity (Brown 1995).

Study Area

The study area is the region around the Dickinson Research Extension Center (DREC) Ranch, Dunn County, western North Dakota, USA. Native vegetation in western North Dakota is the Wheatgrass-Needlegrass Type (Barker and Whitman 1988, Shiflet 1994) of the mixed grass prairie.

The climate of western North Dakota has changed several times during geologic history (Manske 1999). The most recent climate change occurred about 5,000 years ago, to conditions like those of the present, with cycles of wet and dry periods. The wet periods have been cool and humid, with greater amounts of precipitation. A brief wet period occurred around 4,500 years ago. Relatively long periods of wet conditions occurred in the periods between 2,500 and 1,800 years ago and between 1,000 and 700 years ago. Recent short wet periods occurred in the years from 1905 to 1916, 1939 to 1947, and 1962 to 1978. The dry periods have been warmer, with reduced precipitation and recurrent summer droughts. A widespread, long drought period occurred between the years 1270 and 1299, an extremely severe drought occurred from 1863 through 1875, and other more recent drought periods occurred from 1895 to 1902, 1933 to 1938, and 1987 to 1992. The current climatic pattern in western North Dakota is cyclical between wet and dry periods and has existed for the past 5,000 years (Bluemle 1977, Bluemle 1991, Manske 1994a).

Procedures

Daylight duration data for the Dickinson location of latitude 46o48' N, longitude 102 o 48' W, were tabulated from daily sunrise and sunset time tables compiled by the National Weather Service, Bismarck, North Dakota.

Temperature and precipitation data were taken from historical climatological data collected at the Dickinson Research Extension Center Ranch, latitude 47o 14' N, longitude 102o 50' W, Dunn County, near Manning, North Dakota, 1982-2024.

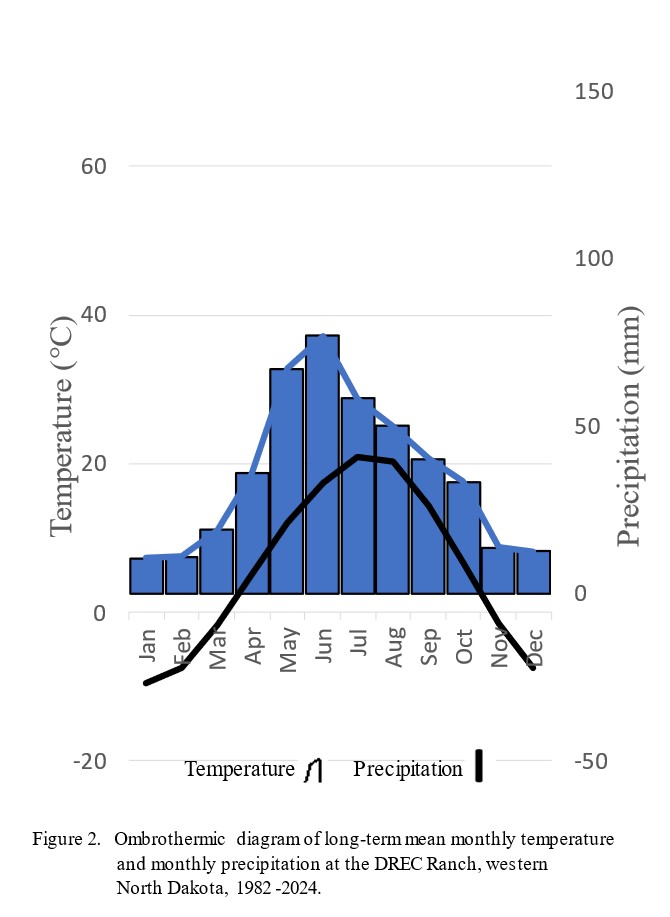

A technique reported by Emberger et al. (1963) was used to develop water deficiency months data from historical temperature and precipitation data. The water deficiency months data were used to identify months with conditions unfavorable for plant growth. This method plots mean monthly temperature (o C) and monthly precipitation (mm) on the same axis, with the scale of the precipitation data at twice that of the temperature data. The temperature and precipitation data are plotted against an axis of time. The resulting ombrothermic diagram shows general monthly trends and identifies months with conditions unfavorable for plant growth. Water deficiency conditions exist during months when the precipitation data bar drops below the temperature data curve and plants are under water stress. Plants are under temperature stress when the temperature curve drops below the freezing mark (0o C).

Results and Discussion

Light

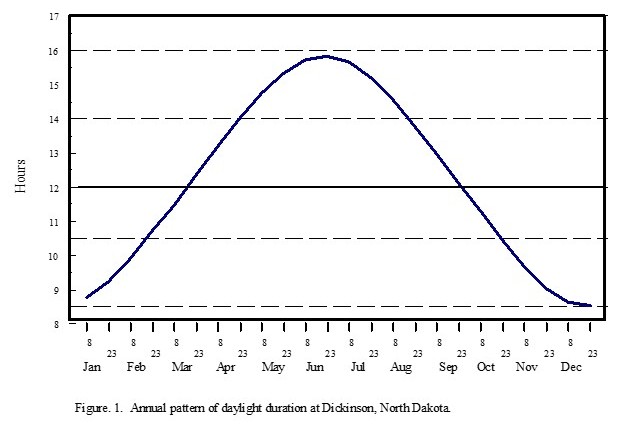

The tilt of the earth’s axis in conjunction with the earth’s annual revolution around the sun produces the seasons and changes the length of daylight in temperate zones. Dickinson (figure 1) has nearly uniform day and night lengths (12 hours) during only a few days, near the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, 20 March and 22 September, respectively, when the sun’s apparent path crosses the equator as the sun travels north or south, respectively. The shortest day length (8 hours, 23 minutes) occurs at winter solstice, 21 December, when the sun’s apparent path is farthest south of the equator. The longest day length (15 hours, 52 minutes) occurs at summer solstice, 21 June, when the sun’s apparent path is farthest north of the equator. The length of daylight during the growing season (mid April to mid October) oscillates from about 13 hours in mid April, increasing to nearly 16 hours in mid June, then decreasing to around 11 hours in mid October (figure 1).

Temperature

The DREC Ranch in western North Dakota experiences severe, windy, dry winters with little snow accumulation. The springs are relatively moist in most years, and the summers are often droughty but are interrupted periodically by thunderstorms. The long-term (43-year) mean annual temperature is 42.3o F (5.7o C) (table 1). January is the coldest month, with a mean temperature of 15.0o F (-9.5o C). July and August are the warmest months, with mean temperatures of 69.7o F (21.0o C) and 68.4o F (20.2o C), respectively. Months with mean monthly temperatures below 32.0o F (0.0o C) are too cold for active plant growth. Low temperatures define the growing season for perennial plants, which is generally from mid April to mid October (6.0 months, 183 days). During the other 6 months each year, plants in western North Dakota cannot conduct active plant growth. Soils are frozen to a depth of 3 to 5 feet for a period of 4 months (121 days) (Larson et al. 1968). The early and late portions of the 6- month growing season have very limited plant activity and growth. The period of active plant growth is generally 5.5 months (168 days).

Western North Dakota has large annual and diurnal changes in monthly and daily air temperatures. The range of seasonal variation of average monthly temperatures between the coldest and warmest months is 55.0o F (30.5o C), and temperature extremes in western North Dakota have a range of 161.0o F (89.4o C), from the highest recorded summer temperature of 114.0o F (45.6o C) to the lowest recorded winter temperature of -47.0o F (-43.9o C). The diurnal temperature change is the difference between the minimum and maximum temperatures observed over a 24-hour period. The average diurnal temperature change during winter is 22.0o F (12.2o C), and the change during summer is 30.0o F (16.7o C). The average annual diurnal change in temperature is 26.0o F (14.4o C) (Jensen 1972). The large diurnal change in temperature during the growing season, which has warm days and cool nights, is beneficial for plant growth because of the effect on the photosynthetic process and respiration rates (Leopold and Kriedemann 1975).

Precipitation

The long-term (43-year) annual precipitation for the Dickinson Research Extension Center Ranch in western North Dakota is 16.91 inches (429.68 mm). The long-term mean monthly precipitation is shown in table 1. The growing-season precipitation (April to October) is 14.28 inches (362.61 mm) and is 85.22% of annual precipitation. June has the greatest monthly precipitation, at 3.04 inches (77.15 mm).

The seasonal distribution of precipitation (table 2) shows the greatest amount of precipitation occurring in the spring (7.11 inches, 42.05%) and the least amount occurring in winter (1.60 inches, 9.46%). Total precipitation received for the 5-month period of November through March averages less than 2.63 inches (15.55%). The precipitation received in the 3-month period of May, June, and July accounts for 47.25% of the annual precipitation (7.99 inches).

The annual and growing-season precipitation levels and percent of the long-term mean for 43 years (1982 to 2024) are shown in table 3. Drought conditions exist when precipitation amounts for a month, growing season, or annual period are 75% or less of the long-term mean. Wet conditions exist when precipitation amounts for a month, growing season, or annual period are 125% or greater of the long-term mean. Normal conditions exist when precipitation amounts for a month, growing season, or annual period are greater than 75% and less than 125% of the long-term mean. Between 1982-2024, 6 drought years (13.95%) (table 4) and 8 wet years (18.60%) (table 5) occurred. Annual precipitation amounts at normal levels, occurred during 29 years (67.44%) (table 3). The area experienced 6 drought growing seasons (13.95%) (table 6) and 8 wet growing seasons (18.60%) (table 7). Growing- season precipitation amounts at normal levels occurred during 29 years (67.44%) (table 3). The 6-year period (1987-1992) was a long period with near-drought conditions. The average annual precipitation for these 6 years was 12.12 inches (307.89 mm), only 71.67% of the long-term mean. The average growing-season precipitation for the 6- year period was 9.97 inches (253.11 mm), only 69.82% of the long-term mean (table 3).

Water Deficiency

Monthly periods with water deficiency conditions are identified on the annual ombrothermic graphs when the precipitation data bar drops below the temperature data curve. On the ombrothermic graphs, periods during which plants are under low-temperature stress are indicated when the temperature curve drops below the freezing mark of 0.0o C (32.0o F). The long-term ombrothermic graph for the DREC Ranch (figure 2) shows that near water deficiency conditions exist for August, September, and October. This finding indicates that range plants generally may have a difficult time growing and accumulating herbage biomass during these 3 months. Favorable water relations occur during May, June, and July, a condition indicating that range plants should be able to grow and accumulate herbage biomass during these 3 months.

The ombrothermic relationships for the Dickinson Research Extension Center Ranch in western North Dakota are shown for each month in table 8. The 43-year period (1982 to 2024) had a total of 258 months during the growing season. Of these growing-season months, 78.5 months had water deficiency conditions, which indicates that range plants were under water stress during 30.4% of the growing-season months (tables 8 and 9): this amounts to an average of 2.0 months during every 6.0-month growing season range plants have been limited in growth and herbage biomass accumulation because of water stress. The converse indicates that only 4.0 months of an average year have conditions in which plants can grow without water stress.

Most growing seasons have months with water deficiency conditions. In only 6 of the 43 years (table 8) did water deficiency conditions not occur in any of the six growing-season months. In each growing-season month of 1982, 2013, 2015, 2016, 2019, and 2023, the amounts and distribution of the precipitation were adequate to prevent water stress in plants. Twenty years (47.51%) had water deficiency for 0.5 to 2.0 months during the growing season. Sixteen years (37.21%) had water deficiency conditions for 2.5 to 4.0 months during the growing season. One year (2.33%), 1988, had water deficiency conditions for 5.0 months during the growing season. None of the 43 years had water deficiency conditions for all 6.0 months of the growing season (table 8). The 6-year period (1987-1992) was a long period with low precipitation; during this period, water deficiency conditions existed for an average of 3.1 months during each growing season, which amounts to 51.33% of this period’s growing-season months (table 8).

May, June, and July are the 3 most important precipitation months and therefore constitute the primary period of production for range plant communities. May and June are the 2 most important months for dependable precipitation. Only 4 (9.30%) of the 43 years had water deficiency conditions during May, and 6 years (13.95%) had water deficiency conditions during June. One year (2017) had water deficiency conditions in both May and June. Fifteen (34.88%) of the 43 years had water deficiency conditions in July (table 9). Only one year (2017) has had water deficiency conditions during May, June, and July (table 8b).

Most of the growth in range plants occurs in May, June, and July (Goetz 1963, Manske 1994b). Peak aboveground herbage biomass production usually occurs during the last 10 days of July, a period that coincides with the time when plants have attained 100% of their growth in height (Manske 1994b). Range grass growth coincides with the 3- month period of May, June, and July, when 47.25% of the annual precipitation occurs.

August, September, and October are not dependable for positive water relations. August and September had water deficiency conditions in 46.51% and 53.49% of the years, respectively, and October had water deficiency conditions in 34.88% of the years (table 9). Visual observations of range grasses with wilted, senescent leaves in August indicate that most plants experience some level of water stress when conditions approach those of water deficiency. August, September, and/or October had water deficiency conditions during 81.40% of the growing seasons in the previous 43 years (table 8). These 3 months make up 42% of the growing season, and they had water deficiency conditions on the average of 45% of the time (table 9). The water relations in August, September, and October limit range plant growth and herbage biomass accumulation.

Over the last 43 years, drought years occurred 14.0% of the time. Drought growing seasons occurred 14.0% of the time. Water deficiency months occurred 30.4% of the time. Water deficiency occurred in May and June 9.3% and 14.0% of the time, respectively. July had water deficiency conditions 34.9% of the time. August, September, and October had water deficiency conditions 46.5%, 53.5%, and 34.9%. Water deficiency periods lasting for a month place plants under water stress severe enough to reduce herbage biomass production. These levels of water stress are a major factor limiting the quantity and quality of plant growth in western North Dakota and can limit livestock production if not considered during the development and implementation of long-term grazing management strategies.

The ombrothermic procedure to identify growing season months with water deficiency treats each month as an independent event. Precipitation during the other months of the year may buffer or enhance the degree of water stress experienced by perennial plants during water deficiency months. The impact of precipitation during other months on the months with water deficiency can be evaluated from annual running total precipitation data (table 10). Water deficiency conditions occurred during 3.5 months in 2024 (table 10).

Conclusion

The vegetation in a region is a result of the total effect of the long-term climatic factors for that region. Ecologically, the most important climatic factors that affect rangeland plant growth are light, temperature, water (precipitation), and water deficiency.

Light is the most important ecological factor because it is necessary for photosynthesis. Changes in time of year and time of day coincide with changes in the angle of incidence of the sun’s rays; these changes cause variations in light intensity. Daylight duration oscillation for each region is the same every year and changes with the seasons. Shading of sunlight by cloud cover and from other plants affects plant growth.

Day-length period is important to plant growth because it functions as a trigger to physiological processes. Most cool-season plants reach flower phenophase between mid-May and mid-June. Most warm-season plants flower between mid-June and mid-September.

Plant growth is limited by both low and high temperatures and occurs within only a narrow range of temperatures, between 32o and 122o F. Perennial plants have a 6-month growing season, between mid-April and mid-October. Diurnal temperature fluctuations of warm days and cool nights are beneficial for plant growth. Cool- season plants have lower optimum temperatures for photosynthesis than do warm-season plants, and cool-season plants do not use water as efficiently as do warm-season plants. Temperature affects evaporation rates, which has a dynamic effect on the annual ratios of cool-season to warm-season plants in the plant communities. A mixture of cool- and warm-season plants is highly desirable because the grass species in a mixture of cool- and warm-season species have a wide range of different optimum temperatures and the herbage biomass production is more stable over wide variations in seasonal temperatures.

Water is essential for living systems. Average annual precipitation received at the DREC Ranch is 16.9 inches, with 84.4% occurring during the growing season and 47.3% occurring in May, June, and July. Plant water stress occurs when the rate of water loss through transpiration exceeds the rate of replacement by absorption. Years

with drought conditions have occurred 14.0% of the time during the past 43 years. Growing seasons with drought conditions have occurred 14.0% of the time.

Water deficiencies exist when the amount of rainfall received is less than evapotranspiration demand. Temperature and precipitation data can be used in ombrothermic graphs to identify monthly periods with water deficiencies. During the past 43 years, 30.4% of the growing-season months had water deficiency conditions that placed range plants under water stress: range plants were limited in growth and herbage biomass accumulation for an average of 2.0 months during every 6-month growing season. May, June, and July had water deficiency conditions 9.3%, 14.0%, and 34.9% of the time, respectively. August, September, and October had water deficiency conditions 46.5%, 53.5% and 34.9% of the time, respectively. One month with water deficiency conditions causes plants to experience water stress severe enough to reduce herbage biomass production.

Most of the growth in range grasses occurs in May, June, and July. In western North Dakota, 100% of range grass leaf growth in height and 86% to 100% of range flower stalk growth in height are completed by 30 July. Peak aboveground herbage biomass production usually occurs during the last 10 days of July, a period that coincides with the time during which plants are attaining 100% of their height. Most range grass growth occurs during the 3- month period of May, June, and July, when 47.3% of the annual precipitation occurs.

Grassland management should be based on phenological growth stages of the major grasses and can be planned by calendar date. Management strategies for a region should consider the climatic factors that affect and limit range plant growth.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to Sheri Schneider for assistance in processing the weather data, compilation of the tables and figures, and production of this manuscript.

| Table 3. Precipitation in inches and percent of long-term mean for perennial plant growing season months, 1982-2024. | |||||||||

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Growing Season |

Annual Total | |

Long-Term Mean 1982-2024 |

1.42

|

2.65 |

3.04 |

2.30 |

1.97 |

1.59 |

1.31 |

14.28 |

16.91 |

| 1982 | 1.37 | 2.69 | 4.30 | 3.54 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 5.75 | 21.09 | 25.31 |

| % of LTM | 96.48 | 101.51 | 141.45 | 153.91 | 88.83 | 106.29 | 438.93 | 147.73 | 149.62 |

| 1983 | 0.21 | 1.53 | 3.26 | 2.56 | 4.45 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 13.59 | 15.55 |

| % of LTM | 14.79 | 57.74 | 107.24 | 111.30 | 225.89 | 54.09 | 54.96 | 95.20 | 91.92 |

| 1984 | 2.87 | 0.00 | 5.30 | 0.11 | 1.92 | 0.53 | 0.96 | 11.69 | 12.88 |

| % of LTM | 202.11 | 0.00 | 174.34 | 4.78 | 97.46 | 33.33 | 73.28 | 81.89 | 76.14 |

| 1985 | 1.24 | 3.25 | 1.58 | 1.07 | 1.84 | 1.69 | 2.13 | 12.80 | 15.13 |

| % of LTM | 87.32 | 122.64 | 51.97 | 46.52 | 93.40 | 106.29 | 162.60 | 89.66 | 89.44 |

| 1986 | 3.13 | 3.68 | 2.58 | 3.04 | 0.46 | 5.29 | 0.18 | 18.36 | 22.96 |

| % of LTM | 220.42 | 138.87 | 84.87 | 132.17 | 23.35 | 332.70 | 13.74 | 128.61 | 135.74 |

| 1987 | 0.10 | 1.38 | 1.15 | 5.39 | 2.65 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 11.53 | 14.13 |

| % of LTM | 7.04 | 52.08 | 37.83 | 234.35 | 134.52 | 49.06 | 6.11 | 80.77 | 83.53 |

| 1988 | 0.00 | 1.85 | 1.70 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 5.30 | 9.03 |

| % of LTM | 0.00 | 69.81 | 55.92 | 38.26 | 1.52 | 45.91 | 8.40 | 37.13 | 53.38 |

| 1989 | 2.92 | 1.73 | 1.63 | 1.30 | 1.36 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 10.60 | 13.07 |

| % of LTM | 205.63 | 65.28 | 53.62 | 56.52 | 69.04 | 44.03 | 73.28 | 74.25 | 77.26 |

| 1990 | 2.03 | 2.39 | 3.75 | 1.13 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 11.14 | 11.97 |

| % of LTM | 142.96 | 90.19 | 123.36 | 49.13 | 15.74 | 42.77 | 64.89 | 78.03 | 70.76 |

| 1991 | 1.97 | 1.16 | 3.95 | 1.43 | 0.55 | 2.17 | 1.31 | 12.54 | 13.30 |

| % of LTM | 138.73 | 43.77 | 129.93 | 62.17 | 27.92 | 136.48 | 100.00 | 87.84 | 78.62 |

| 1992 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 1.59 | 2.70 | 2.02 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 8.68 | 11.23 |

| % of LTM | 57.04 | 25.66 | 52.30 | 117.39 | 102.54 | 45.28 | 12.21 | 60.80 | 66.38 |

| 1993 | 1.41 | 1.71 | 4.57 | 5.10 | 1.24 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 14.26 | 17.36 |

| % of LTM | 99.30 | 64.53 | 150.33 | 221.74 | 62.94 | 11.32 | 3.82 | 99.89 | 102.62 |

| 1994 | 0.86 | 1.46 | 4.51 | 1.07 | 0.31 | 1.08 | 4.58 | 13.87 | 16.14 |

| % of LTM | 60.56 | 55.09 | 148.36 | 46.52 | 15.74 | 67.92 | 349.62 | 97.16 | 95.41 |

| Table 3 (cont). Precipitation in inches and percent of long-term mean for perennial plant growing season months, 1982- 2024. | |||||||||

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Growing Season |

Annual Total | |

Long-Term Mean 1982-2024 |

1.42 |

2.65 |

3.04 |

2.30 |

1.97 |

1.59 |

1.31 |

14.28 |

16.91 |

| 1995 | 1.01 | 4.32 | 0.68 | 4.62 | 3.16 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 14.46 | 16.24 |

| % of LTM | 71.13 | 163.02 | 22.37 | 200.87 | 160.41 | 0.00 | 51.15 | 101.29 | 96.00 |

| 1996 | 0.14 | 3.07 | 1.86 | 2.55 | 1.72 | 2.51 | 0.09 | 11.94 | 15.97 |

| % of LTM | 9.86 | 115.85 | 61.18 | 110.87 | 87.31 | 157.86 | 6.87 | 83.64 | 94.40 |

| 1997 | 2.89 | 0.95 | 5.02 | 5.41 | 0.76 | 1.75 | 0.78 | 17.56 | 18.61 |

| % of LTM | 203.52 | 35.85 | 165.13 | 235.22 | 38.58 | 110.06 | 59.54 | 123.01 | 110.01 |

| 1998 | 0.40 | 1.51 | 5.98 | 2.11 | 4.60 | 0.71 | 4.38 | 19.69 | 22.42 |

| % of LTM | 28.17 | 56.98 | 196.71 | 91.74 | 233.50 | 44.65 | 334.35 | 137.93 | 132.53 |

| 1999 | 1.10 | 4.93 | 1.59 | 1.80 | 2.70 | 2.40 | 0.00 | 14.52 | 15.56 |

| % of LTM | 77.46 | 186.04 | 52.30 | 78.26 | 137.06 | 150.94 | 0.00 | 101.71 | 91.98 |

| 2000 | 1.26 | 1.90 | 3.77 | 2.77 | 2.74 | 1.09 | 1.46 | 14.99 | 20.23 |

| % of LTM | 88.73 | 71.70 | 124.01 | 120.43 | 139.09 | 68.55 | 111.45 | 105.00 | 119.59 |

| 2001 | 2.70 | 0.53 | 6.36 | 4.87 | 0.00 | 1.94 | 0.00 | 16.40 | 18.03 |

| % of LTM | 190.14 | 20.00 | 209.21 | 211.74 | 0.00 | 122.01 | 0.00 | 114.88 | 106.58 |

| 2002 | 1.14 | 2.18 | 5.40 | 4.27 | 4.24 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 18.85 | 21.88 |

| % of LTM | 80.28 | 82.26 | 177.63 | 185.65 | 215.23 | 46.54 | 67.18 | 132.04 | 129.34 |

| 2003 | 1.30 | 4.34 | 1.42 | 2.03 | 0.82 | 2.37 | 0.74 | 13.02 | 19.12 |

| % of LTM | 91.55 | 163.77 | 46.71 | 88.26 | 41.62 | 149.06 | 56.49 | 91.20 | 113.03 |

| 2004 | 0.89 | 1.31 | 1.65 | 2.30 | 0.93 | 2.57 | 3.10 | 12.75 | 16.51 |

| % of LTM | 62.68 | 49.43 | 54.28 | 100.00 | 47.21 | 161.64 | 236.64 | 89.31 | 97.60 |

| 2005 | 0.96 | 6.01 | 6.05 | 0.60 | 1.52 | 0.50 | 1.96 | 17.60 | 21.51 |

| % of LTM | 67.61 | 226.79 | 199.01 | 26.09 | 77.16 | 31.45 | 149.62 | 123.29 | 127.15 |

| 2006 | 2.78 | 2.82 | 2.13 | 0.96 | 2.87 | 1.42 | 2.01 | 14.99 | 17.70 |

| % of LTM | 195.77 | 106.42 | 70.07 | 41.74 | 145.69 | 89.31 | 153.44 | 105.00 | 104.63 |

| 2007 | 1.58 | 4.64 | 1.80 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.26 | 10.87 | 13.94 |

| of LTM | 111.27 | 175.09 | 59.21 | 45.65 | 39.59 | 47.80 | 19.85 | 76.14 | 82.40 |

| Table 3 (cont). Precipitation in inches and percent of long-term mean for perennial plant growing season months, 1982- 2024. | |||||||||

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Growing Season |

Annual Total | |

Long-Term Mean 1982-2024 |

1.42 |

2.65 |

3.04 |

2.30 |

1.97 |

1.59 |

1.31 |

14.28 |

16.91 |

| 2008 | 0.61 | 2.79 | 4.02 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.68 | 12.22 | 14.88 |

| % of LTM | 42.96 | 105.28 | 132.24 | 46.09 | 51.78 | 65.41 | 128.24 | 85.60 | 87.96 |

| 2009 | 1.49 | 2.47 | 3.84 | 3.24 | 0.95 | 1.15 | 1.95 | 15.09 | 17.89 |

| % of LTM | 104.93 | 93.21 | 126.32 | 140.87 | 48.22 | 72.33 | 148.86 | 105.70 | 105.75 |

| 2010 | 1.43 | 3.70 | 3.50 | 1.94 | 1.39 | 4.09 | 0.13 | 16.18 | 19.03 |

| % of LTM | 100.70 | 139.62 | 115.13 | 84.35 | 70.56 | 257.23 | 9.92 | 113.34 | 112.49 |

| 2011 | 1.66 | 6.87 | 2.15 | 2.33 | 2.70 | 1.76 | 0.44 | 17.91 | 21.28 |

| % of LTM | 116.90 | 259.25 | 70.72 | 101.30 | 137.06 | 110.69 | 33.59 | 125.46 | 125.79 |

| 2012 | 2.38 | 1.58 | 4.31 | 1.98 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 2.35 | 13.63 | 15.46 |

| % of LTM | 167.61 | 59.62 | 141.78 | 86.09 | 41.62 | 13.21 | 179.39 | 95.48 | 91.39 |

| 2013 | 1.05 | 7.55 | 2.23 | 2.13 | 2.81 | 2.44 | 3.35 | 21.56 | 23.22 |

| % of LTM | 73.94 | 284.91 | 73.36 | 92.61 | 142.64 | 153.46 | 255.73 | 151.02 | 137.26 |

| 2014 | 1.41 | 3.73 | 3.38 | 0.37 | 8.84 | 1.03 | 0.59 | 19.35 | 21.11 |

| % of LTM | 99.30 | 140.75 | 111.18 | 16.09 | 448.73 | 64.78 | 45.04 | 135.54 | 124.79 |

| 2015 | 0.60 | 1.65 | 4.68 | 2.87 | 1.69 | 1.35 | 1.96 | 14.80 | 17.01 |

| % of LTM | 42.25 | 62.26 | 153.95 | 124.78 | 85.79 | 84.91 | 149.62 | 103.67 | 100.55 |

| 2016 | 3.44 | 2.26 | 1.96 | 3.61 | 1.86 | 2.66 | 1.80 | 17.59 | 19.70 |

| % of LTM | 242.25 | 85.28 | 64.47 | 156.96 | 94.42 | 180.95 | 137.40 | 123.22 | 116.45 |

| 2017 | 1.30 | 0.84 | 1.27 | 0.72 | 2.67 | 2.28 | 0.08 | 9.16 | 10.55 |

| % of LTM | 91.55 | 31.70 | 41.78 | 31.30 | 135.53 | 143.40 | 6.11 | 64.16 | 62.36 |

| 2018 | 0.48 | 1.22 | 4.23 | 2.01 | 0.55 | 1.84 | 0.66 | 10.99 | 14.39 |

| % of LTM | 33.80 | 46.04 | 139.14 | 87.39 | 27.92 | 115.72 | 50.38 | 76.98 | 85.06 |

| 2019 | 1.35 | 2.52 | 2.60 | 1.61 | 4.70 | 9.10 | 1.26 | 23.14 | 25.88 |

| % of LTM | 95.07 | 95.09 | 85.53 | 70.00 | 238.58 | 572.33 | 96.18 | 162.09 | 152.99 |

| 2020 | 0.59 | 1.45 | 1.10 | 2.67 | 2.56 | 0.86 | 0.26 | 9.49 | 11.01 |

| % of LTM | 41.55 | 54.72 | 36.18 | 116.09 | 129.95 | 54.09 | 19.85 | 66.48 | 65.08 |

| Table 3 (cont). Precipitation in inches and percent of long-term mean for perennial plant growing season months, 1982- 2024. | |||||||||

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Growing Season |

Annual Total | |

Long-Term Mean 1982-2024 |

1.42 |

2.65 |

3.04 |

2.30 |

1.97 |

1.59 |

1.31 |

14.28 |

16.91 |

| 2021 | 0.26 | 5.07 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.63 | 0.14 | 2.70 | 11.90 | 13.75 |

| % of LTM | 18.31 | 191.32 | 35.20 | 44.78 | 82.74 | 8.81 | 206.11 | 83.36 | 81.28 |

| 2022 | 4.16 | 3.17 | 2.02 | 3.71 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 1.84 | 16.11 | 20.16 |

| % of LTM | 292.96 | 119.62 | 66.45 | 161.30 | 14.21 | 58.49 | 140.46 | 112.85 | 119.17 |

| 2023 | 0.30 | 2.69 | 1.91 | 2.21 | 3.25 | 1.32 | 1.24 | 12.92 | 15.42 |

| % of LTM | 21.13 | 101.51 | 62.83 | 96.09 | 164.97 | 83.02 | 94.66 | 90.50 | 91.15 |

| 2024 | 1.35 | 2.35 | 2.75 | 0.88 | 1.28 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 8.73 | 10.89 |

| % of LTM | 95.07 | 88.68 | 90.46 | 38.26 | 64.97 | 7.55 | 0.00 | 61.15 | 64.37 |

| |||||||||||

| APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | SEP | OCT | #Months | % 6 Months 15 Apr-15 Oct | |||

| Total | 6 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 20 | 23 | 15 | 78.5 | 30.4 | ||

% of 43 YEARS | 14.0 | 9.3 | 14.0 | 34.9 | 46.5 | 53.5 | 34.9 | ||||

| Table 10. Monthly precipitation and running total precipitation compared to the long-term mean (LTM), 2024. | ||||||

Monthly Precipitation (in) | Running Total Precipitation (in) | |||||

Months |

LTM 1982-2023 |

Precipitation 2024 |

% of LTM | Running LTM 1982-2023 | Running Precipitation 2024 |

% of LTM |

| Jan | 0.43 | 0.23 | 53.49 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 53.49 |

| Feb | 0.43 | 0.29 | 67.44 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 60.47 |

| Mar | 0.76 | 0.57 | 75.00 | 1.62 | 1.09 | 67.28 |

| Apr | 1.42 | 1.35 | 95.07 | 3.04 | 2.44 | 80.26 |

| May | 2.66 | 2.35 | 88.35 | 5.70 | 4.79 | 84.04 |

| Jun | 3.04 | 2.75 | 90.46 | 8.74 | 7.54 | 86.27 |

| Jul | 2.34 | 0.88 | 37.61 | 11.08 | 8.42 | 75.99 |

| Aug | 1.99 | 1.28 | 64.32 | 13.07 | 9.70 | 74.22 |

| Sep | 1.62 | 0.12 | 7.41 | 14.69 | 9.82 | 66.85 |

| Oct | 1.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.03 | 9.82 | 61.26 |

| Nov | 0.55 | 0.15 | 27.27 | 16.58 | 9.97 | 60.13 |

| Dec | 0.48 | 0.92 | 191.67 | 17.06 | 10.89 | 63.83 |

| Total | 17.06 | 10.89 | 63.83 |

|

|

|

Literature Cited

Barbour, M.G., J.H. Burk, and W.D. Pitts. 1987. Terrestrial plant ecology. The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Co., Menlo Park, CA. 634p.

Barker, W.T., and W.C. Whitman. 1988. Vegetation of the Northern Great Plains. Rangelands 10:266-272.

Bluemle, J.P. 1977. The face of North Dakota: the geologic story. North Dakota Geological Survey. Ed. Series 11. 73p.

Bluemle, J.P. 1991. The face of North Dakota: revised edition. North Dakota Geological Survey. Ed. Series 21. 177p.

Brown, R.W. 1977. Water relations of range plants. Pages 97-140. in R.E. Sosebee (ed.) Rangeland plant physiology. Range Science Series No. 4. Society for Range Management. Denver, CO.

Brown, R.W. 1995. The water relations of range plants: adaptations to water deficits. Pages 291-413. in D.J. Bedunah and R.E. Sosebee (eds.). Wildland plants: physiological ecology and developmental morphology. Society for Range Management. Denver, CO.

Coyne, P.I., M.J. Trlica, and C.E. Owensby. 1995. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics in range plants. Pages 59-167. in D.J. Bedunah and R.E. Sosebee (eds.). Wildland plants: physiological ecology and developmental morphology. Society for Range Management. Denver, CO.

Dahl, B.E., and D.N. Hyder. 1977. Developmental morphology and management implications. Pages 257-290. in R.E. Sosebee (ed.). Rangeland plant physiology. Range Science Series No. 4. Society for Range Management. Denver, CO.

Dahl, B.E. 1995. Developmental morphology of plants. Pages 22-58. in D.J. Bedunah and R.E. Sosebee (eds.). Wildland plants: physiological ecology and developmental morphology. Society for Range Management. Denver, CO.

Daubenmire, R.F. 1974. Plants and environment. John Wiley and Sons. New York, NY. 422p.

Dickinson Research Center. 1982-2024. Temperature and precipitation weather data.

Emberger, C., H. Gaussen, M. Kassas, and A. dePhilippis. 1963. Bioclimatic map of the Mediterranean Zone, explanatory notes. UNESCO-FAO. Paris. 58p.

Goetz, H. 1963. Growth and development of native range plants in the mixed grass prairie of western North Dakota. M.S. Thesis, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND. 165p.

Jensen, R.E. 1972. Climate of North Dakota. National Weather Service, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND. 48p.

Langer, R.H.M. 1972. How grasses grow. Edward Arnold. London, Great Britain. 60p.

Larson, K.E., A.F. Bahr, W. Freymiller, R. Kukowski, D. Opdahl, H. Stoner, P.K. Weiser, D. Patterson, and

O. Olson. 1968. Soil survey of Stark County, North Dakota. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. 116p.+ plates.

Leopold, A.C., and P.E. Kriedemann. 1975. Plant growth and development. McGraw-Hill Book Co. New York, NY. 545p.

Manske, L.L. 1994a. History and land use practices in the Little Missouri Badlands and western North Dakota. Proceedings- Leafy spurge strategic planning workshop. USDI National Park Service, Dickinson, ND. p. 3-16.

Manske, L.L. 1994b. Problems to consider when implementing grazing management practices in the Northern Great Plains. NDSU Dickinson Research Extesion Center. Range Management Report DREC 94-1005, Dickinson, ND. 11p.

Manske, L.L. 1999. Prehistorical conditions of rangelands in the Northern Great Plains. NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center. Summary Range Management Report DREC 99-3015, Dickinson, ND. 5p.

Manske, L.L. 2011. Range plant growth and development are affected by climatic factors. NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center. Summary Range Management Report DREC 11-3019c, Dickinson, ND. 5p.

McMillan, C. 1957. Nature of the plant community. III. Flowering behavior within two grassland communities under reciprocal transplanting. American Journal of Botany 44 (2): 144-153.

National Weather Service. 1996. Sunrise and sunset time tables for Dickinson, North Dakota. National Weather Service, Bismarck, ND. 1p.

Odum, E.P. 1971. Fundamentals of ecology. W.B. Saunders Company. Philadelphia, PA. 574p.

Ramirez, J.M. 1972. The agroclimatology of North Dakota, Part 1. Air temperature and growing degree days. Extension Bulletin No. 15. North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND. 44p.

Roberts, R.M. 1939. Further studies of the effects of temperature and other environmental factors upon the photoperiodic response of plants. Journal of Agricultural Research 59(9): 699-709.

Shiflet, T.N. (ed.). 1994. Rangeland cover types. Society for Range Management. Denver, CO. 152p.

Weier, T.E., C.R. Stocking, and M.G. Barbour. 1974. Botany: an introduction to plant biology. John Wiley and Sons. New York, NY. 693p.

Wildryes as Fall Complementary Pastures for the Northern Plains

Llewellyn L. Manske PhD

Scientist of Rangeland Research

North Dakota State University

Dickinson Research Extension Center

Report DREC 25-4032b

Fall Complementary Pastures

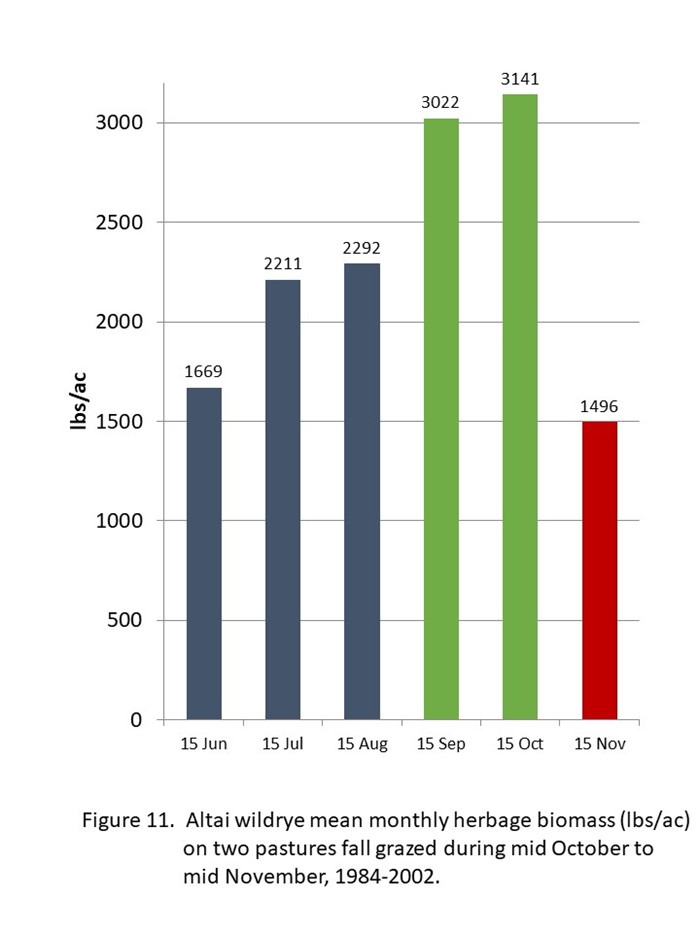

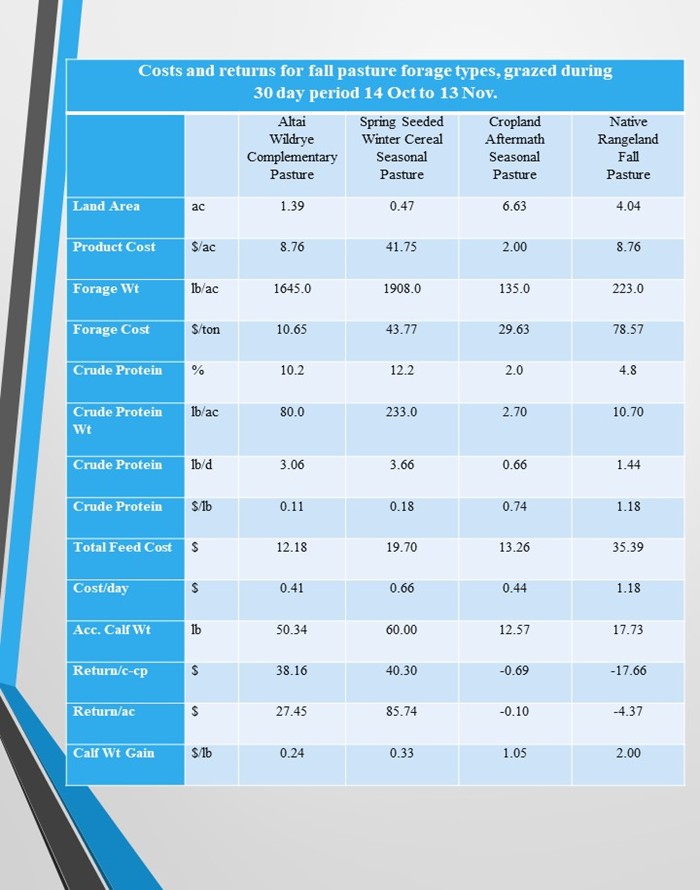

The wildryes are the only perennial grass type that retains adequate nutritional quality to meet a lactating cows requirements during fall grazing from mid-October to mid-November. Despite these unique important characteristics, wildryes are not a popular fall pasture in the Northern Plains. The problem isn’t the grasses. The problem is the management. The wildryes do not grow and behave like native grasses of the Northern Mixed Grass Prairie and cannot be managed with the same techniques that the native grasses are managed. The native grasses plus crested wheatgrass and smooth bromegrass grow and behave as if they were types of perennial spring wheat. The wildrye grasses grow and behave as if they were types of perennial winter wheat. Proper management of wildrye fall pastures must be adjusted to accommodate these differences in growth and behavior.

There are numerous types of wildryes in the world. The two common types in the Northern Plains are Altai and Russian Wildryes.

Altai wildrye, Leymus angustus (Trin.) Pilg., is a member of the grass family, Poaceae, tribe, Triticeae, syn.: Elymus angustus Trin., and is a long lived perennial, monocot, cool-season, mid grass, that is drought tolerant, very winter hardy, highly tolerant of saline soils nearly at the level of tall wheatgrass, and fairly tolerant of alkaline soils. Altai wildrye was introduced into Canada as two seed lots. The first seed lot arrived in 1934 from Voronezh, USSR, located in the far western European Russian Steppe. The second seed lot arrived in 1939 from the Steppe of Kustanay located in the northern region of Kazakhstan. Three synthetic strains were developed from seed increase plots started in 1950 at the Swift Current Research Station followed by more sites at seven research stations in Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, which produced the first released cultivar, Prairieland, in 1976. Seed from the increase fields at Swift Current was used to establish 60 acres of Altai wildrye monoculture at the NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center for a replicated study of late season grazing during mid-October to mid-November conducted from 1983 to 2005 for 23 years. Early aerial growth consists of basal leaves from crown tiller buds. Basal leaf blades are 15-25 cm (6-10 in) long, 0.5-0.7 cm wide, erect, coarse, light green to bluegreen to blue, and can remain upright under deep wet snow. The leaf sheath is usually shorter than the internodes and grayish green. The membrane ligule is 0.5-1.0 mm long with an obtuse apex. Some early specimens of introduced strains showed vigorous rhizome charateristics and aggressive spreading which was considered to be undesirable. The available released plant material are generally weakly rhizomatous with short rhizomes. Unfortunately, fields seeded with plant material that has nonaggressive short rhizomes is limited by around a 20 to 25 year life expectancy. However, the uniquely deep extensive fibrous root system that can penetrate to depths of 3-4 m (9.8-13.1 ft) and efficiently absorb available soil water was retained. Regeneration is primarily asexual propagation by crown and short rhizome tiller buds. Seedlings have slow, weak growth and are successful only when competition from established plants is nonexistant. Flower stalks are erect, 60-100 cm (24-39 in) tall, mostly leafless and few in numbers. Inflorescence is a terminal spike 15-20 cm (6-8 in) long, 1 cm in diameter, that has closely spread overlapping spikelets of 2 or 3 florets, with 2 or 3 spikelets per node. Basal leaves are palatable to livestock and seed stalks are not. Wildryes maintain slightly higher levels of protein and digestibility with advancing maturity better than other species of perennial grasses. Wildryes are best used for late season grazing from mid-October to mid-November. Fire top kills aerial parts and kills deeply into the crown when soil is dry. Fire halts the processes of the four major defoliation resistance mechanisms and causes great reduction in biomass production and tiller density. This summary information on growth development and regeneration of Altai wildrye was based on works of Lawrence 1976, and St. John et al. 2010.