Bee-utiful Landscapes: Building a Pollinator Garden

(H1811 Revised January 2025)This publication helps gardeners identify major pollinators, choose plants that will provide a continuous source of nectar and pollen during the growing season, and safely use pesticides.

Patrick Beauzay, Extension Research Specialist

Janet Knodel, Extension Entomologist

Contact your county NDSU Extension office to request a printed copy.

NDSU staff can order copies online (login required).

Bees are in trouble in the United States. Native bee species are declining in numbers due to habitat loss, climate change, pathogens, pesticides and other factors. Two bumble bee species, Franklin’s bumble bee and the rusty patched bumble bee, are listed on the federally endangered list.

Additionally, one-fourth to half of honey bee colonies in the U.S. die each year due to stressors, including a parasitic varroa mite that vectors several diseases. Fortunately, honey bees are not endangered. Beekeepers are able to split their colonies and purchase new queen bees. However, these challenges increase costs and labor for North Dakota’s numerous beekeepers.

The challenges facing native bees and honey bees are concerning because they pollinate many fruit, nut and vegetable crops. Furthermore, bees provide pollinator services for a limited number of agronomic crops. Therefore, habitat conservation and development are important for consumers, beekeepers and farmers.

Individuals, families and businesses can have a major impact on bee populations in North Dakota by providing suitable habitat and nutrition. By planting a pollinator garden, you can turn your yard, farm or balcony into an oasis for bees.

This publication helps gardeners identify major pollinators, choose plants that will provide a continuous source of nectar and pollen during the growing season, and safely use pesticides.

The Importance of Pollinators

Many of our nuts, fruits and vegetables are pollinated by bees.

Nearly one out of every three mouthfuls of food comes from a bee-pollinated crop.

In a world without bees, we wouldn’t have apples, blueberries, avocados, almonds, squash, melons, and many more fruits and vegetables. See Table 1. Our diet would be bland, less nutritious and definitely less colorful.

How Pollination Occurs

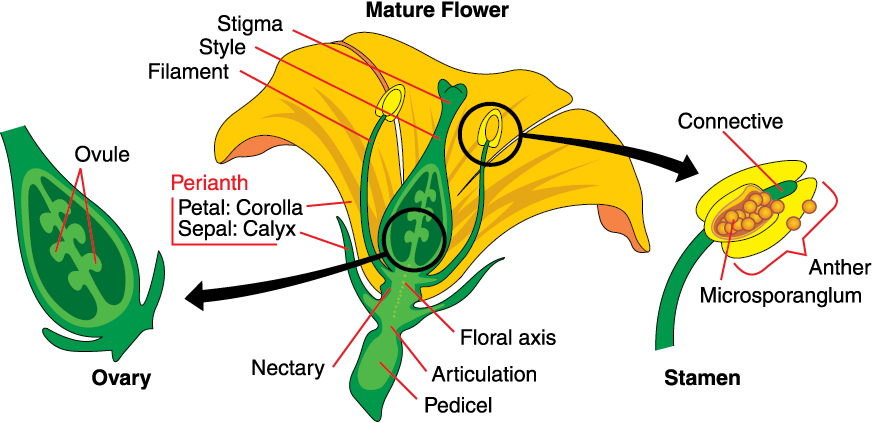

Pollination is the transfer of pollen grains from the anther (male) to a receptive pistil (female). Once deposited on the tip of the pistil (stigma), the pollen grain germinates and a pollen tube grows down the length of the pistil (style) to the ovary. The pollen tube transports two male gametes that fertilize an egg (ovule) and another cell to produce an embryo and endosperm to nourish the embryo (Figure 1). The embryo, endosperm and a portion of the ovule become a seed.

Pollen transfer can occur within the same flower (self-pollination), between two separate flowers on the same plant (still considered self-pollination) or between two separate flowers on two different plants of the same species (cross-pollination), depending on the pollination mechanism.

The purpose of pollination is to ensure the next generation by producing seeds. After pollination and fertilization occur, seeds are produced in what we call a botanical fruit. A botanical fruit is simply a seedbearing structure and can include fresh produce that we normally consider to be vegetables. Apples, peppers and cucumbers are common products of pollination and are derived from the plant’s ovary tissue.

Table 1. Common backyard fruit and vegetable crops and whether they require bee pollination.

Information derived from the 2015 U.S. Department of Agriculture document titled “Attractiveness of Agricultural Crops to Pollinating Bees for the Collection of Nectar and/or Pollen.”

Generally, pollination occurs in two ways: wind and animal. Agronomic crops such as wheat, soybeans and corn are wind-pollinated. No insects are required for an ear of corn to develop. The wind simply blows the pollen from one plant to another. Showy flowers are unnecessary in wind-pollinated plants because they have no need to attract an insect pollinator.

Animal pollination requires an insect, bird or mammal to carry pollen from one flower to another. This publication will focus on insect pollination, but hummingbird plant preferences will be mentioned in Tables 3-5.

Cucurbits such as melons, squash, zucchini, pumpkins and most cucumbers depend on bees for pollination because they have separate male and female flowers on the same plant. For pollination to occur, a bee must visit a male flower and then deliver the sticky pollen to a female flower.

Cross-pollination

Plants have different pollination mechanisms. Some plants require cross-pollination, meaning that they require pollen from a plant that is genetically different. Fruit trees such as apples, pears and American plums require pollen from a different variety of tree.

For example, a Honeycrisp apple flower must receive pollen from another apple variety, such as Haralson or Cortland. A Honeycrisp tree will not produce fruit if only Honeycrisp pollen is available. Bees are an important means of ensuring cross-pollination in fruit trees.

Self-pollination

Other plants such as tomatoes, are self-pollinated. This means that pollen from another plant is not necessary. When the wind vibrates the anther at the right frequency, pollen is released and lands on the pistil, resulting in self pollination.

However, new research shows that bumble bees improve fruit production even in self-pollinated species. Bumble bees engage in a practice of buzz pollination. They grasp the flower and rapidly vibrate their flight muscles at the right frequency to release tomato pollen.

In a recent study, researchers discovered that bumble bees increased the number of tomatoes by 45%, compared with wind pollination. Honey bees are unable to pollinate tomatoes because they are unable to perform buzz pollination.

Pollinator Decline

European Honey Bees

North Dakota is the nation’s leader in honey production. In 2023, North Dakota beekeepers produced 38.3 million pounds of honey, which is over one quarter of the nation’s total honey production. The state’s 511,000 colonies of European honey bees (Apis mllifera) are distributed throughout the state and spend their summers foraging for nectar and pollen on clover, alfalfa and other flowering plants (Figure 2).

Honey bees were brought to North America first by European colonists in the 1600s. Unlike native bees, honey bees have a hard time wintering in North Dakota unless their hives are well-insulated. During the winter, the majority of honey bees are shipped to California and other warm states to overwinter and then pollinate almond, vegetable and fruit crops in late winter (Figure 3).

Colony collapse disorder (CCD) was frequently covered in the news media several years ago. This disorder is manifested by the sudden disappearance of adult worker bees with no dead bodies in the colony. The queen and her larvae are the only inhabitants left in the colony.

With CCD on the decline in recent years, winter die-off is the bigger concern for the honey bee industry. Approximately 30% of colonies die each winter.

The cause of CCD and winter die-off still are being studied, but a multitude of factors appear to play a role. Varroa mites are parasites that feed on the blood of honey bees. Fungal, bacterial and viral diseases further weaken the bees.

Other potential factors include migratory stress as colonies are shipped between North Dakota and other states, as well as poor nutrition. Honey bees may feed on a single crop such as almond flowers for two or more weeks when they are shipped to California and other southern states. Diverse sources of forage are better for their health than a single source.

In addition, insecticides that are commonly used in food crops, gardens and yards to control insect pests can cause direct mortality bee kills and/or have sublethal effects on the health of bees. Sublethal effects on bees include reduced foraging ability and hive production (fewer queens produced). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified a group of insecticides highly toxic to bees called neonicotinoids, which are absorbed and translocated within plants to other plant parts like pollen and nectar. Bees are exposed to neonicotinoids by contaminated nectar and pollen, contaminated seed dust and direct exposure to foliar sprays or toxic residues on plant parts. Furthermore, pesticides contribute to the overall decline of bees and increase the threat of extinction for many bee species.

Bumble Bees

Bumble bees (Bombus spp.) are the most well-known of the native bee species (Figure 4). Their wide, fuzzy bodies seem to defy the laws of physics as they fly through the air. Of the 46 species native to North America, about 18 species call North Dakota home.

They live in social colonies with a single queen. Depending on their species, each colony can house 50 to 1,000 individuals. Unlike honey bees, many bumble bee species live underground in abandoned rodent burrows, and they do not store honey.

Bumble bees are better adapted to cold weather than their European cousins and can fly on cold, cloudy days when honey bees are confined to the hive. Consequently, bumble bees can be better pollinators of early spring fruit trees such as apple and plum in North Dakota (Table 1).

Bumble bee colonies are annual. Each spring, a single, pregnant queen emerges from her underground burrow, feeds on nectar and pollen from early spring flowers, and then begins constructing her nest. The nest can be above-ground or underground, depending on the bumble bee species.

The queen proceeds to lay eggs that will hatch into female worker bees that will forage for food, take care of the larvae and defend the colony. In late summer, the queen produces male bees that will mate with young, large females that will become next year’s queens. The whole colony, with the exception of the newly fertilized queens, dies as fall progresses.

Although bumble bees are not susceptible to CCD and winter die-off, many species are in decline. Of the species that are native to North Dakota, three and possibly more species appear to have decreasing populations.

A parasitic fungus called Nosema bombi appears to be undermining the health of a few native species. Researchers hypothesize that commercial bumble bees that were sold to pollinate greenhouse crops may have escaped and introduced this fungal parasite into the native bumble bee population in the U.S.

Loss of habitat and suitable forage also may impact native bumble bee populations. As native prairie and Conservation Reserve Program lands are converted to cropland, native wildflowers and flowering weeds that provide much-needed nectar and pollen become less abundant.

The life cycle of bumble bees shows the need for a continuous supply of nectar and pollen from early spring through late fall. As native flowering plants give way to corn, wheat and soybean fields, suitable bumble bee habitat is eliminated or fragmented.

Most bumble bee species can travel only

one-third to one mile in search of flowers,

while honey bees can travel 2½ miles. Therefore, bumble bees are more limited in their foraging ability.

Our towns and cities also may be inhospitable places for bumble bees. Vast expanses of weed-free lawns provide no food or nesting habitat for bees. Overuse of pesticides, such as insecticides and fungicides, also may have a detrimental effect on bumble bees.

Solitary Bees

Most bee species do not live in social colonies like honey bees and bumble bees. Solitary bee species have short lives and produce a single generation of bees. They have no worker bees; each bee outfits her own nest and lays eggs in cells.

Most solitary bees, such as cellophane bees and green sweat bees, live in underground nests that they have excavated. About one-third of solitary bees, such as mason bees, leafcutter bees and masked bees, nest in dead plant stems or small holes in trees that have been drilled by woodpeckers or wood-boring insects.

Less is known about the status of solitary bee species in North Dakota. However, solitary bees such as mason bees can be important pollinators of backyard orchards and vegetable gardens.

Bee Identification

Bees belong to the Order Hymenoptera, which includes wasps, ants and bees. Bees are very diverse in color, shape, size and nesting habits, but they generally are easy to recognize as “bees.”

Color can range from black-brown with yellow-white hair markings to metallic green-blue, and size ranges from as small as 5 millimeters (mm) to as large as 25 mm. They can be found anywhere, especially where flowers are available for food (nectar and pollen).

Some general characteristics of bees are:

■ Head: The head of the bee is round to heart-shaped, and has long, narrow eyes on the side.

■ Thorax: Two pairs of wings are found on the thorax (Figure 5a). The front and hind wings are connected by small hooks called hamuli (Figure 5b). The front wing has one to three closed cells along the leading edge of the wing called submarginal cells that are used in identification (Figure 5a).

■ Abdomen: The abdomen of female bees has a stinger that is used primarily for defense of the nest. Most stings of native bees are weak and more annoying than painful. Their behavior is usually nonaggressive toward people unless defending their nest.

■ Special Characteristics:

• Most bees have hairy bodies, giving them a fuzzy appearance (Figure 6). Hairs are branched but must be viewed under a microscope or magnifying lens (10x) to see the branches (Figure 7).

• For carrying pollen, most species have areas of pollen-collecting hairs (scopae) on the rear legs or underneath the abdomen (Figures 8a and b) or long, stiff, inward-curving hairs surrounding a flat area on the rear legs forming a pollen-collecting basket (corbicula, Figure 9).

Bee Mimics

Other insects look and even sound like bees, but they are not bees. These bee mimics include some flies and wasps.

Flies

Flies are easy to distinguish from bees because they have only two wings; in contrast, a bee has four wings. Second, flies usually have short antennae with only three segments; bees have long, segmented antennae, with 12 segments for females and 13 segments for males.

The compound eye of flies is large and takes up most of the head, whereas bee eyes are limited to the sides of the head. The hoverfly or flower fly (Family Syrphidae) looks like a bee with yellow and black markings on the body and even buzzes like a bee when pollinating flowering plants (Figures 11a and b).

Another fly group that mimics bees is called the bee fly (Family Bombyllidae), which feeds on nectar and pollen as valuable pollinators (Figures 12a and b).

Wasps

Wasps belong to the Order Hymenoptera, like bees, and hence have some of the characteristics of bees, such as four wings, a stinger and long antennae. However, wasps have sparse and simple hairs, while bees are hairy on most of the body, with branched hairs.

Second, wasps have narrow, round hind legs in cross section, compared with bees, which have wide, flat hind legs that are modified with pollen-collecting hairs, or pollen basket.

The body of a wasp has a narrow “waist” between the thorax and abdomen, while bees do not. The yellow and black markings of wasps are more brightly colored than bees and indicate “warning” to any predator or person who disturbs them.

Wasps can sting more than once because their stinger is not barbed like it is on bees and it stays with the insect. A good example is yellow-jackets or hornets (Family Vespidae), which are more aggressive and likely to sting people during late summer (Figure 13). Yellow-jackets are predators of bees and other insects and also feed on flower nectar.

Nests of some wasps are made of mud or paper that hangs from trees or buildings, such as the bald-faced hornet’s nest. Bees do not construct these types of nests.

Table 2

Table 2. Key Identification Characteristics and Nesting Sites of the Major Bee Families in North Dakota.

| Common Name Family | Size | Key Identification Characteristics | Nesting Sites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mining bee Andrenidae | Small to medium (6-18 mm) | Front of face of females has large, shallow depressions (called facial fovea) with short velvety hairs (sometimes white) between eyes and antennae. Looks like eyebrows (Figure 14a). Short-tongued. Second submarginal cell is smaller than third submarginal cell (Figure 14b). Generally black with pale hair stripes on abdomen. Pollen-collecting hairs on rear legs and | Nest solitary in ground, often in large aggregations. Prefers to build nests in lawns with sandy soils near or under shrubs. |

| Cellophane bee Colletidae | Small to medium (7-15 mm) | Slender body with light bands of hair on When viewed from the front, heads Short-tongued (unique two-lobed tongue). Second submarginal cell is the same size Pollen-collecting hairs on the upper part Many Colletes spp. are specialists and | Nest solitary in ground, but some in large aggregations. Line their |

| Masked bee Colletidae | Small (<7 mm) | Bodies are shiny, slender, hairless and wasplike (Figure 16a). Females lack pollen-collecting hairs, store pollen and nectar in their crops (honey stomach). They regurgitate it for young in nest. Most have some facial markings, yellow Short-tongued. | Nest solitary in hollow branches and cavities, some in the ground. |

| Sweat bees Halictidae | Small to medium (5-15 mm) | Bright metallic green, dull metallic green Basal wing vein strongly arched Pollen-carrying hairs on rear legs. Short-tongued. Attracted to the salt when you sweat. | Nest in soil, solitary to semisocial to some communal nesters. |

| Leaf-cutting bees Megachilidae | Medium to large (7-20 mm) | Pollen-collecting hairs on ventral surface Stout, dark body with light bands of hair Head as broad as thorax with large mouthparts to cut leaves. Cut round pieces of leaves to line nests (Figure 18b). This small amount of leaf removal is Long-tongued. | Nest solitary in holes or cavities (natural or man-made). |

| Mason bees Megachilidae | Small to medium (5-15 mm) | Pollen-collecting hairs on ventral surface Robust round body, two color types: Some species are used commercially Efficient pollinators of many crops; for example, Megachile rotundata (alfalfa Long-tongued. | Solitary or nest in groups in artificial nesting structures (Figure 19b) (widely available at garden supply stores or build your own). |

| European honey bee (Apis mellifera)Apidae | Medium (10-15 mm) | Hairy body, golden brown with dark Hind tibia with pollen basket Hind tibia without spurs. Long-tongued. Swarm to find new nesting sites. | Nest in man-made hives and in open cavities, such as stumps or hollow tree cavities. Social bees. |

| Bumble bees (Bombus spp.)Apidae | Medium to large (10-23 mm) | Robust, very hairy (fuzzy), often black Long-tongued. Hind tibia with pollen basket (or corbicula) (Figure 21b). Hind tibia with spurs. Pollinates in cool, cloudy weather. Makes low buzzing sound when flying Many species are in decline due to introduced diseases. | Nest underground, commonly in old rodent burrows or grass tussocks. Social bees. |

| Long-horned bees and Digger bees Apidae | Small to large (7-18 mm) | Long-horned bees: Black body with dense pale hairs on Long-tongued. Males have long antennae (Figure 22a). Females have pollen-collecting hairs Digger bees: (Figure 22b) Robust, round, hairy bees. Long-tongued. Females have pollen-collecting hairs Fast-flying bees. | Most species are solitary to communal ground nesters. Digger bees prefer to nest gregariously in lawns with dry, sandy soil. |

Planting a Pollinator Garden

We can help pollinators by designing our yards to become a hospitable haven for pollinators such as honey bees and native bees. The first step is to incorporate a variety of flowering plants into the landscape. You can beautify your yard and help the bees at the same time. Additional steps include providing a water source, creating a suitable habitat or shelter, and limiting use of detrimental pesticides.

Plants for Bees

While flowers dazzle us with their color and beauty, honey bees and native bees see flowers as a food source. Sugary nectar provides carbohydrates to help power the bees as they go about their daily foraging.

Nectar usually is produced deep within the flower, which increases the chances for bees to come in contact with the pollen-coated anthers. Bees also deliberately collect pollen as an important source of protein. They combine pollen

and nectar to make bee bread, a nourishing food source for bee larvae.

With the diversity of native bees in North Dakota, many species are active at any given time throughout the entire growing season. In addition, some species produce multiple generations of bees throughout the year. Therefore, providing a continuous supply of blooming plants from early spring through fall is important.

To satisfy short-tongued and long-tongued bee species, plant flowers in a variety of colors and shapes. Generally, bees prefer flowers that are white, yellow, purple, violet or blue. Butterflies are attracted to the same colors, plus red and pink.

Native plants are extremely important to bees because these plants co-evolved with our native pollinators. Therefore, they are more likely to provide larger quantities of nectar and pollen and bees may be more attracted to them.

Native plants should make up the majority of species in a pollinator garden. Many beautiful native plants are listed in Tables 3 and 5. If you select native plants that are well-suited to your soil type and precipitation levels, your pollinator garden will be low-maintenance, too.

Some non-native ornamentals, such as catmint and salvia, also may provide valuable pollinator services. If you decide to plant a non-native species in a pollinator garden, choose one that is not double-flowered.

A plant that is double-flowered is bred to have an extra set of petals that replaces important reproductive parts such as stamens or pistils (Figure 23). These types of “improved” cultivars may not produce pollen or nectar. Alternatively, the extra petals may block the pollinator from reaching the pollen or nectar.

A quick and easy perennial pollinator garden can be designed from the choices offered in Table 3. By choosing

two or more plant species from each seasonal category,

you can ensure many weeks of beautiful blooms in your garden.

Spring

■ Spring-flowering perennials such as crocus, grape hyacinth, prairie smoke and wild columbine provide important early sources of nectar for hungry bumble bee queens. Not all spring flowers are equally beneficial. Most tulips and daffodils have been heavily hybridized and will not attract bees.

June

■ Golden Alexander, a North Dakota prairie native, is an important June-blooming perennial. Its flat clusters of yellow flowers resemble dill. In addition to providing abundant nectar for bees, this plant is an important host plant for caterpillars that will later transform into black swallowtail butterflies.

■ Orange-flowered butterfly weed provides cheerful flowers that begin to bloom in June and continue for an extended period of time (Figure 24). Although butterfly weed is a milkweed, it provides benefits for more than just butterflies. Many milkweeds are rich sources of nectar for bees. Although butterfly weed is not native to North Dakota, it is native to South Dakota and Minnesota. This plant grows best in drier soils, so it is a good choice for the western half of North Dakota.

Summer

The summer-flowering category (Table 3) lists many choices to adorn your garden and feed the bees.

■ Anise hyssop is a member of the mint family and is a magnet for bees. This adaptable plant is equally at home in the ornamental garden (Figure 25) as the herb garden. The licorice-scented leaves can be made into herbal teas. The plants are relatively short-lived but will reseed to ensure a steady supply.

■ Echinacea, otherwise known as purple coneflower, is a popular pollinator garden choice. The flower’s spiny brown cone offers a convenient place for insects to land, sip nectar and gather pollen (Figure 26). A wide variety of insects congregate around Echinacea plants. The only downside to these plants is that they are rather short-lived.

■ Native blazing stars are all-stars of pollinator gardens. Natives such prairie blazing star and meadow blazing star (Figure 27) draw many more visitors than cultivated varieties, such as ‘Kobold.’ Prairie blazing star blooms in July and is better adapted to clay soils, while meadow blazing star blooms in August and can take drier soils.

Fall

Fall-blooming flowers are especially important to allow new bumble bee queens to grow and mate with males to ensure the next generation.

■ Tall sedums, although not native, are a staple of the fall pollinator garden. They are especially useful in well-drained soils.

■ Showy golden rod is one of the better native golden rods for garden use. Unlike other species, it does not spread by rhizomes.

■ New England aster (Figure 28) is probably the most important of the fall perennials because it is one of the last perennials to bloom in the garden and provides nectar and pollen when food is scarce.

To ensure that bees will find your pollinator garden, plant at least three plants of each flowering perennial species. Not only will the bees be more likely to find a grouping of the same flowering plants, they also will be able to gather a substantial amount of nectar and pollen in one place. Joe Pye weed would be the exception because that plant is relatively large and three plants of this species would overwhelm the average garden.

If you discover that you have gaps in flowering in your perennial pollinator garden, incorporating a few annual bedding plants can help (Table 4). Many annuals are sold while flowering and will continue to produce flowers for most of the summer. Common bedding plants such as lantana (Figure 29) and zinnia (Figure 30) not only will draw bees, they also may attract butterflies and hummingbirds.

Other Beneficial Plantings

Herbs also can be beneficial to bees (Table 4). Borage is an underutilized herb that is an absolute bee magnet. Its purplish-blue flowers are extremely attractive to bees (Figure 31). Borage is a good herb to incorporate in and around vegetable gardens to ensure a steady supply of pollinators. However, beware of its propensity to self-seed vigorously.

When selecting trees and shrubs for your landscape, don’t forget that they can be great sources of nectar and pollen, particularly in spring. May-flowering fruit trees and shrubs, such as apples, chokecherries, plums, tart cherries, honeyberries and Juneberries, provide a very important food source when very little is blooming in perennial gardens (Table 5).

Boulevard trees can be beneficial to bees, too. The wonderfully fragrant blossoms of linden (basswood) trees seem to draw every bee on the block when the trees bloom in late June into early July. Honey produced from linden trees is prized because of its golden brown color and its depth of flavor.

Other beneficial boulevard trees include honey locust, Kentucky coffee tree and Ohio buckeye (Table 5). Common wind-pollinated trees, such as ash, are not very attractive to bees and do not produce nectar.

Table 3

Table 3. Perennials by Bloom Time

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Perennial or Annual | Native | Pollinators | Bloom Time | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPRING FLOWERING PERENNIALS | ||||||

| Spring crocus | Crocus spp. | Perennial | B | March-April | The first spring bulb to bloom in North Dakota; great source of pollen and nectar for hungry bumble bee queens; bulbs must be planted in the fall. | |

| Grape hyacinth | Muscari spp. | Perennial | B | April | Bulbs must be planted in the fall. | |

| American pasqueflower | Pulsatilla patens | Perennial | X | B | April-May | One of the first native plants in bloom. Grows throughout North Dakota. |

| Prairie smoke | Geum triflorum | Perennial | X | B | April-May | Grows well throughout North Dakota; has great, feathery seedheads that resemble smoke. |

| Red columbine | Aquilegia canadensis | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | May-early June | Best planted in shade; red color attracts hummingbirds. |

| Wild geranium | Geranium maculatum | Perennial | X | B, BF | May-early June | Woodland native adapted for shade to part-sun environments |

| Jacob’s ladder | Polemonium reptans | Perennial | B, BF | May-early June | Native to Minnesota and South Dakota; best planted in shade | |

| Wild blue phlox | Phlox divaricata | Perennial | B, BF | May-early June | Native to Minnesota and South Dakota; best planted in shade; will slowly spread | |

| Prairie violet | Viola pedatifida | Perennial | X | B, BF | April-June | Does not spread like some violet species; host plant for Fritillary butterflies |

| JUNE FLOWERING PERENNIALS | ||||||

| Golden Alexander | Zizia aurea | Perennial | X | B, BF | May-June | Yellow clusters of flowers resemble dill. Butterfly host plant. |

| Butterfly milkweed | Asclepias tuberosa | Perennial | B, BF, H | June-July | Native to South Dakota and Minnesota but not North Dakota; great orange flowers; best grown in western North Dakota on well-drained soils. | |

| False indigo | Baptisia spp. | Perennial | B, BF | June | Great choice for June-blooming plant. | |

| Catmint | Nepeta x faassenii | Perennial | B | June | ‘Walkers Low’ is popular in the trade; cut back after blooming for a second flush of blooms later in the season. | |

| Salvia | Salvia nemorosa | Perennial | B, BF | June | ‘May Night’ is the old standby; will rebloom if they are cut back after blooming. | |

| Large beardtongue | Penstemon grandifloras | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | May-June | Likes drier soils; very showy flowers |

| Foxglove beardtongue | Penstemon digitalis | Perennial | B, BF, H | June-July | Native to Minnesota and South Dakota; commercial cultivars are available | |

| Lance-leaf coreopsis | Coreopsis lanceolata | Perennial | B, BF | June-August | Native to Minnesota; prefers medium to dry soil conditions | |

| Harebell | Campanula rotundifolia | Perennial | X | B | June-August | Beautiful blue bell-shaped flowers; does well in dry, rocky soils |

| Anise hyssop | Agastache foeniculum | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | June-September | May be short-lived in the garden but will reseed |

| Culver’s root | Veronicastrum virginicum | Perennial | X | B, BF | June-August | Great architectural plant; provides tall vertical accent; may spread by rhizomes |

| Upright prairie coneflower | Ratibida columnifera | Perennial | X | B, BF | June-August | Features a long cone with yellow petals that hang down; will self-seed |

| SUMMER FLOWERING PERENNIALS | ||||||

| Purple prairie clover | Dalea purpurea | Perennial | X | B, BF | July-Aug. | Grows well throughout North Dakota; has a great “landing pad” for butterflies. |

| Swamp milkweed | Asclepias incarnata | Perennial | X | B, BF | July | Best grown in the eastern half of North Dakota; grows well in a garden setting. |

| Black-eyed Susan | Rudbeckia spp. (R. hirta is native) | Perennial | X | B, BF | July-Sept. | Great all-around pollinator plant; seedheads will feed the birds in winter. |

| Prairie blazing star | Liatris pycnostachya | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | July-Aug. | Best grown in loamy to clay soils. |

| Purple coneflower | Echinacea spp. (E. angustifolium is native) | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | July-Aug. | If choosing an ornamental cultivar, do not choose one that is double-flowered. |

| Bee balm | Monarda fistulosa | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | July-Aug. | Native species can spread aggressively; cultivars may be better behaved in a garden setting; red cultivars will attract hummingbirds. |

| Spotted bee balm | Monarda punctata | Perennial | B, BF | July-August | Native to Minnesota; unusual plant with pink, cream and green leaves; grows best in sandy soils | |

| Joe Pye weed | Eutrochium maculatum (recent name change) | Perennial | X | B, BF | July-Aug. | Grows best in moist soils; many ornamental cultivars are available in different heights. |

| Fireworks goldenrod | Solidago rugosa ‘Fireworks’ | Perennial | B, BF | Aug. | More ornamental than stiff golden rod. | |

| Meadow blazing star | Liatris ligulistylis | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | Aug. | Will grow in all parts of North Dakota with the exception of the southwestern quarter of the state; one of the best plants for monarchs. |

| FALL FLOWERING PERENNIALS | ||||||

| Sneezeweed | Helenium autumnale | Perennial | X | B, BF | Aug.-Sept. | Doesn’t actually cause sneezing. Likes moist soils. |

| Tall sedum | Hylotelephium telephium (formerly in the Sedum genus) | Perennial | B, BF | Sept.-Oct. | ‘Autumn Joy’ or any of the tall, fall-blooming sedums are great pollinator plants. Grows best in drier soils. | |

| New England Aster | Symphyotrichum novae-angliae | Perennial | X | B, BF, H | Sept.- Oct. | One of the last blooming plants in the garden. Absolutely covered in bees. |

| Showy goldenrod | Solidago speciosa | Perennial | X | B, BF | September-November | Not as aggressive as other goldenrod species |

| Smooth blue aster | Symphyotrichum laeve | Perennial | X | B, BF | August-September | Lovely blue flowers; plant may require staking because it lodges |

| Aromatic aster | Symphyotrichum oblongifolium | Perennial | X | B, BF | September-November | October Skies cultivar is a better choice than the species because it blooms earlier; one of the last blooming plants in the garden |

B is for bee; BF is for butterfly and H is for hummingbird.

Please note that bloom times are approximate. Bloom times may vary, depending upon weather and other factors.

Table 4

Table 4. Annuals and Herbs That Nourish Pollinators

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Perennial or Annual | Pollinators | Comments |

| ANNUALS | ||||

| Alyssum | Lobularia maritima | Annual | B, BF | Very fragrant. |

| Cleome | Cleome hassleriana | Annual | B, BF, H | Great for a cottage garden. |

| Cosmos | Cosmos spp. | Annual | B, BF | Easy to grow from seed. |

| Egyptian starcluster | Pentas lanceolata | Annual | B, BF | Underutilized annual; butterfly magnet. |

| Lantana | Lantana camara | Annual | B, BF, H | Very drought-tolerant; butterfly magnet. |

| Marigold | Tagetes spp. | Annual | B, BF | Very common garden annual. |

| Salvia | Salvia spp. | Annual | B, BF | Many cultivars attract butterflies |

| Sunflower | Helianthus annuus | Annual | B, BF | Many varieties are available. |

| Verbena | Verbena spp. | Annual | B, BF | Verbena bonariensis (tall verbena) is beautiful but may self-seed vigorously. |

| Zinnia | Zinnia spp. | Annual | B, BF, H | Avoid double-flowered varieties. |

| HERBS | ||||

| Basil | Ocimum basilicum | Annual | B | Let your basil flower. |

| Borage | Borago officinalis | Annual | B | Will reseed very readily; absolute bee magnet. |

| Chives | Allium schoenoprasum | Perennial | B, BF | A perennial herb that blooms in late spring when flowering plants are scarce. |

| Dill | Anethum graveolens | Annual | B, BF | Important caterpillar host plant. |

| Lavender | Lavandula angustifolia | Annual | B, BF, H | All-around good pollinator plant. |

| Oregano | Origanum vulgare | Annual | B, BF | Let your oregano flower. |

B is for bee; BF is for butterfly and H is for hummingbird.

Please note that bloom times are approximate. Bloom times may vary, depending upon weather and other factors.

Table 5

Table 5. Pollinator Trees and Shrubs

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Tree or Shrub | Native | Pollinators | Bloom Time | Maximum Height (ft.) | Light Exposure | Hardiness Zone |

| BOULEVARD TREES | ||||||||

| Honey locust | Gleditsia triacanthos | Tree | X | B | May-June | 50 | Full sun | 4* |

| Kentucky coffeetree | Gymnocladus dioicus | Tree | X | B, BF, H | May-June | 60 | Full sun | Plant only south of I-94 in North Dakota |

| Linden | Tilia americana | Tree | X | B, M | June-July | 70 | Full sun | 3-4 |

| Ohio buckeye | Aesculus glabra | Tree | B, H | May | 35 | Full sun | 3 | |

| SMALL TREES/LARGE SHRUBS | ||||||||

| Apple | Malus spp. | Tree | B | May | ** | Full sun | ** | |

| Chokecherry | Prunus virginiana | Tree | X | B | May | 25 | Full sun to light shade | 2 |

| Crabapple | Malus spp. | Tree | B | May | ** | Full sun | ** | |

| False indigo | Amorpha fruticosa | Shrub | X | B | June | 12 | Full sun to light shade | 2 |

| Gray dogwood | Cornus racemosa | Tree or shrub | X | B, BF | June | 25 | Full sun to shade | 3 |

| Hawthorn | Crataegus mollis and other spp. | Tree | X | B, BF | May | ** | Full sun | 4 |

| Nannyberry | Viburnum lentago | Shrub | X | B, BF | May-June | 14 | Full sun to partial shade | 2 |

| Pagoda dogwood | Cornus alternifolia | Tree | B | June | 20 | Full sun to partial shade | 4 | |

| Plum | Prunus americana and other spp. | Tree | X | B, BF, M | May | 20 | Full sun | 3 |

| Smooth sumac | Rhus glabra | Shrub | X | B, BF | July | 15 | Full sun to partial shade | 3 |

| SHRUBS | ||||||||

| American cranberrybush | Viburnum trilobum | Shrub | X | B | May | 12 | Full sun to partial shade | 3 |

| Black chokeberry | Aronia melanocarpa | Shrub | B | May-June | 6 | Full sun to light shade | 3 | |

| Common snowberry | Symphoricarpos albus | Shrub | X | B, BF, M | June-July | 6 | Full sun to partial shade | 3 |

| Dwarf bush honeysuckle | Diervilla lonicera | Shrub | X | B, M | June-Aug. | 4 | Full sun to partial shade | 3 |

| Golden currant | Ribes aureum | Shrub | X | B, BF, M | May | 6 | Full sun to partial shade | 2 |

| Honeyberry | Lonicera caerulea | Shrub | B | May | 8 | Full sun | 2 | |

| Juneberry (Saskatoon) | Amelanchier alnifolia | Tree | X | B | May-June | 6 | Full sun | 2 |

| Leadplant | Amorpha canescens | Shrub | X | B, BF, M | June-Aug. | 3 | Full sun to partial shade | 2 |

| Ninebark | Physocarpus opulifolius | Shrub | X | B, BF | June-July | 10 | Full sun to partial shade | 3 |

| Prairie rose | Rosa arkansana | Shrub | X | B | June-July | 3 | Full sun | 2 |

| Redosier dogwood | Cornus sericea | Shrub | X | B, BF | May-June | 10 | Full sun to partial shade | 2 |

B is for bees, BF is for butterflies, M is for moth, H is for hummingbird

*NDSU’s release, Northern Acclaim® Honeylocust is hardy to zone 3.

**Varies with cultivar

Provide Suitable Habitat

Nearly 70% of bees live in nests below the ground.

To accommodate these ground-nesting bees, leave some dry, bare ground on your property where they can nest.

Bees usually prefer to nest in sandy slopes. Native bunch grasses such as prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) and little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) also provide shelter for ground-nesting bumble bees.

The other 30% of bees live in cavities, such as plant stems or holes bored in trees by woodpeckers and beetle larvae. Some bees nest in hollow stems while others have the ability to excavate the core of stems to facilitate egg-laying.

The easiest way to provide habitat for these cavity nesters is to postpone cleaning up your perennial flower beds until the following spring. Leave the dead stalks until the spring daytime temperatures are consistently in the 50s. If you wish to clean up your garden early in the spring, leave the dead debris on top of your compost pile so the bees can hatch and fly away.

Another option is to purchase or build a bee house for cavity-nesting bees. Two common bee houses are on the market. One type features a block of untreated wood that is 5 by 8 inches with 0.1- to 0.4 inch-diameter holes drilled in it (Figure 35).

The depth of the holes is critical. Small holes (less than ¼ inch diameter) should be a minimum of 3 to 4 inches deep, and large holes (more than ¼ inch diameter) should be at least 6 inches deep. Holes that are too short will result in only male eggs being laid.

The second type features 15 to 20 hollow canes or reeds with one end closed. The hollow tubes are cut to 6 to 8 inches and tied together. Make sure the hollow tubes have a closed end and stay dry.

Nesting boxes should be located in a sheltered spot about 3 to 6 feet high with entrances facing east or southeast for the morning sun. Your best option is to fix the nesting boxes to a post, building or tree so they don’t move in the wind.

Bee house maintenance is important to prevent diseases and other pests. Tubes should be cleaned out or replaced each spring after the bees have hatched and vacated.

Building bee houses is a great summer activity for kids. Directions for building nests for native bees are available at The Xerces Society website listed in Other Resources.

Provide a Water Source

Bees require a water source because they need to supplement the liquid found in nectar. If you don’t have a pond or creek on your property, you can provide a small water source. A bird bath or fountain certainly is attractive, but simpler water sources are acceptable (Figure 36).

Adding water to a plant saucer with rocks or glass beads is easy and quick. The rocks or beads provide a place for the bees to land because they cannot land on water. To prevent mosquitoes from breeding, change the water at least twice a week.

Wise Pesticide Use

Besides having food and nesting sites, protection from pesticides is critical if native bees are to survive in your flower garden. Insecticide spraying on blooming flowers is especially deadly for all bee species. In addition, spraying herbicides to kill weeds in gardens or lawns removes the diversity and abundance of flowering plants needed by bees throughout the growing season.

An integrated pest management approach should be used to promote judicious use of pesticides for pest control only when needed and to implement scouting and nonpesticide pest management strategies, such as cultural control, biological control or host plant resistance.

When an insecticide is necessary, select a product that is designated as “least toxic” to bees but still reduces pest levels on plants. Some examples of common organic pesticides that have low toxicity to bees are Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis), garlic, kaolin clay and neem.

Remember, any broad-spectrum insecticide can kill “all” insects, including bees and natural enemies of the target pest. Choose the least hazardous formulation of an insecticide product for bee safety (Table 6).

Application is recommended in the late evening or when temperatures are below 55 F, when most bees are not foraging. Remember, some bees such as bumble bees forage in cooler temperatures (down to 50 F) and are actively foraging in the early morning and late evening, much longer than honey bees.

Use short-residual insecticides. “Spot” treat instead of broadcast spraying to minimize the area treated with insecticide. Remember to use all pesticides in a manner consistent with the label. Read, understand and follow the pesticide’s label directions.

If the bee hazard icon is on the label, this indicates that this product is highly toxic to bees and specific application restrictions apply to protect pollinators. An example of a highly toxic substance to bees is the active ingredient imidacloprid or clothianidin in the neonicotinoid insecticide class (systemic). Avoid buying garden plants that are treated with these bee-killing systemic insecticides from garden centers.

Table 6. Different pesticide formulations and general toxicity to bees.

Honey Bee Swarms

Honey bees will swarm at times. This means that more than half of the bees will leave with a new queen to find a new place to live. This can be alarming for people the first time they see it. Swarming bees should be left alone and usually will not bother people.

The swarm will gather in a cluster approximately 150 yards from the hive and bee scouts will go out looking for a new place for the colony to live. They prefer dark holes, such as hollow tree trunks, meat smokers, grills (Figure 37), attic spaces and other man-made items/spaces.

When the bee scouts find a suitable location, they return to the swarm and perform a waggle dance to relay the information to the rest of the swarm. They will begin to build combs, gather honey and pollen, and the queen will start laying eggs in the new location.

If a colony decides to establish itself in an undesirable place (Figure 38), we recommend you have a beekeeping professional remove the bees (Figure 39). Any honey left after the bees are removed will ferment with a bad odor, attract dermestid beetles such as larder beetles, and potentially cause structural damage.

If you have questions on honey bee swarms or removal, please contact the state apiary inspector for North Dakota at www.ndda.nd.gov/divisions/plant-industries/apiary-honey-bees.

Pollinator Garden Summary

❏ Choose two or more perennial species from each seasonal flowering category (spring, June, summer and fall) for a minimum

of eight plant species in the pollinator garden.

❏ Plant multiples of each species.

❏ Select predominantly native species for your pollinator garden.

❏ Avoid planting cultivars with extra petals (double-flowered).

❏ Create a water source.

❏ Provide habitat for ground-nesting and cavity-nesting bees.

❏ Be wise in your use of pesticides and avoid spraying blooming plants.

Sources of Plants and Other Materials

Sources for pollinator garden plants and other materials are provided on this NDSU Master Gardener Program website: www.ag.ndsu.edu/mastergardener.

Other Resources

Calles Torres, V., P.B. Beauzay, E. McGinnis, A.H. Knudson, B. Laschkewitsch, H. Hatterman-Valenti, and J.J. Knodel. 2023. Pollinators and other insect visitations on native and ornamental perennials in two landscapes. HortScience 58(8): 922-934.

Calles-Torrez, V., E. McGinnis, P. Beauzay, N. Walton, J. Landis, and J. Knodel. 2019. Insects That Look Like Bees. NDSU Extension Pub. No. 1914 https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/insects-look-bees

Holm, Heather. 2014. Pollinators of Native Plants. Pollination Press LLC: Minnetonka, Minn.

Lowenstein, D., N. Walton, P. Beauzay, V. Calles-Torrez, G. Fauske, E. McGinnis, and J. Knodel. 2020. Meet the Threatened, Rare and Endangered Insect Pollinators of North Dakota. NDSU Extension Pub. No. E1977

https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/meet-threatened-rare-and-endangered-insect-pollinators-north-dakota

McGinnis E., N. Walton, E. Elsner, and J. Knodel. 2018. Pollination in Vegetable Gardens and Backyard Fruits. NDSU Extension Pub. No. H1898

https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/pollination-vegetable-gardens-and-backyard-fruits

Pei, C.K., T.J. Hovick, R.F. Limb, J.P. Harmon, and B.A. Geaumont. 2022. Bumble bee (Bombus) species distribution, phenology, and diet in North Dakota. Prairie Naturalist Special Issue 1: 11-29.

The Xerxes Society. 2016. Pollinator Conservation.

www.xerces.org/pollinator-conservation/

Xerxes Society. 2016 . How neonicotinoids can kill bees.

https://xerces.org/sites/default/files/2018-05/16-022_01_XercesSoc_How-Neonicotinoids-Can-Kill-Bees_web.pdf

Bee Identification Resources