2025: Efficacy of Insecticide Seed treatments on Hessian Fly in Spring Wheat

(Research Report, Langdon REC, December 2025)Patrick Beauzay, Janet Knodel

Introduction

Hessian fly, Mayetiola destructor (Say), is one of the most significant insect pests affecting wheat in North Dakota. It was introduced into North America during the late 1770s in Long Island, New York, primarily through straw-bedding of Hessian soldiers during the American Revolution (Schmid et al. 2018). Since then, its populations have spread across the wheat-growing regions of the country. Although wheat is the preferred host, it also infests barley, rye and several grass species as alternative hosts. Hessian fly causes injury in two main ways: 1) Larvae feeding at the base of the plants at early growth stages leads to stunting, seedling or tiller death and 2) Larvae feeding on stems, at the nodes in later growth stages weakens the stems, reduces grain filling or causes stem lodging.

Historically, Hessian fly has been a serious pest in winter wheat in southern states and a sporadic pest in ND, with notable outbreaks occurring in 1991, 2003 and 2015 (Knodel, 2015). However, in recent years, significant lodging and yield losses due to Hessian Fly have been observed in spring wheat fields in Cavalier County (Anitha Chirumamilla personal survey). These observations prompted a research study, funded by the North Dakota Wheat Commission, conducted in 2023 and 2024 to monitor the distribution, population density and emergence patterns of Hessian fly in ND using sex pheromone trapping. Results from this study indicated a significant presence of Hessian fly across the state. In 2024, IPM insect trappers captured a total of 12,530 Hessian flies on sticky traps at 27 sites from June to mid-August, an eight-fold increase, compared to 2023 when only 1,527 flies were captured at 37 sites. The highest trap catches were found in the northeast and east-central regions of North Dakota, where 500 to >1500 Hessian flies were captured per trap per season in Pembina, Rolette, Grand Forks, Steele, Cavalier and Nelson counties.

With the increasing Hessian fly numbers and associated yield losses in ND, spring wheat growers are seeking effective management options for this pest. Historically, Hessian fly management has focused on strategies developed for winter wheat systems, which include use of resistant varieties, fly-free planting dates, and insecticides (seed treatments and foliar insecticides). Seed treatments at higher doses have been shown to reduce Hessian fly infestations in winter wheat (Howell et al. 2017, Buntin et al. 2025). However, these studies were not specifically focused on managing Hessian fly in spring wheat, and there is currently no published data on the effectiveness of insecticide seed treatments for spring wheat.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of several registered insecticide seed treatments for spring wheat in controlling Hessian fly populations in North Dakota. This insect produces two generations per season, infesting spring wheat during both the early seedling stage and later developmental stages. Although insecticide seed treatments typically provide protection only against the first generation, reducing early-season infestations may suppress overall population levels enough to diminish the impact of the second generation.

Materials & Methods

In 2025, field experiments were conducted at two sites in northeastern ND: the Langdon Research Extension Center in Langdon and at a farmer’s field located 8 miles from Grand Forks where high numbers of Hessian flies have been observed in the past. However, no Hessian fly infestations occurred at the Grand Forks site during the trial period, resulting in no usable data. Consequently, this location is omitted from further analysis and discussion in this report.

At Langdon REC location, spring wheat was planted on May 27th due to unusually wet conditions early in the season. Individual research plots were 3.5 feet wide and 16 feet long, consisting of seven rows spaced 6 inches apart, using an Almaco planter at a seeding rate of 1.5 million live seeds per acre. Standard fertilizer was applied to target a yield of 60 bushels per acre, and weeds were controlled using appropriate herbicides.

A total of five insecticide seed treatments were evaluated, rather than the seven originally planned, due to the unavailability of insecticide, Foothold Extra. The treatments included in the study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: List of insecticide treatments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Treatment number | Treatment | Rate (fl oz/cwt) | Active Ingredient | IRAC MOA |

1 | Untreated Check | - | - | - |

2 | Gaucho 600 | 0.13 | Imidacloprid | 4A |

3 | Gaucho 600 | 2.4 | Imidacloprid | 4A |

4 | Cruiser | 0.75 | Thiamethoxam | 4A |

5 | Cruiser | 1.33 | Thiamethoxam | 4A |

6 | Lumivia CPL | 0.75 | Chlorantraniliprole | 28 |

The experiment was arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. Plant stand was measured by counting all plants within two 3-feet sections of row in each plot. Hessian fly populations were assessed by collecting 20 random tillers or stems from the outer rows of each plot and dissecting them in the laboratory to determine the number of larvae or pupae per stem. An exception was made at the tillering stage, when entire plants were removed instead, as individual tillers are difficult to separate at this early growth stage. During this stage, Hessian fly larvae and pupae are typically located near the crown region close to the soil surface.

Hessian fly sampling was conducted at the tillering, boot, milk, and late-dough growth stages; the corresponding sampling dates are provided in Table 2. Plots were harvested using a small-plot combine. Harvest was delayed due to rainfall. Plot weight, grain moisture, and test weight were recorded using the combine’s onboard weighing system. Plot weights were adjusted to the standard grain moisture (13.5%) and converted to pounds per acre and bushels per acre.

All data were analyzed using analysis of variance for a complete-block, balanced, orthogonal design using Genovix Version II software. Treatment means were separated using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test.

Table 2. Sampling activities, sampling dates, and crop stages

| Activity | Date | Crop Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Stand Count | June 11 | 2-leaf stage |

| Population count 1 | June 20 | Tillering |

| Population count 2 | July 10 | Boot stage |

| Population count 3 | July 30 | Milk stage |

| Population count 4 | August 22 | Dough stage |

Results and Discussion:

Larval/Pupal Counts

Hessian fly larvae or pupae were not detected in the first two evaluations conducted at the tillering and boot stages. Two factors may explain the absence of counts at these early growth stages:

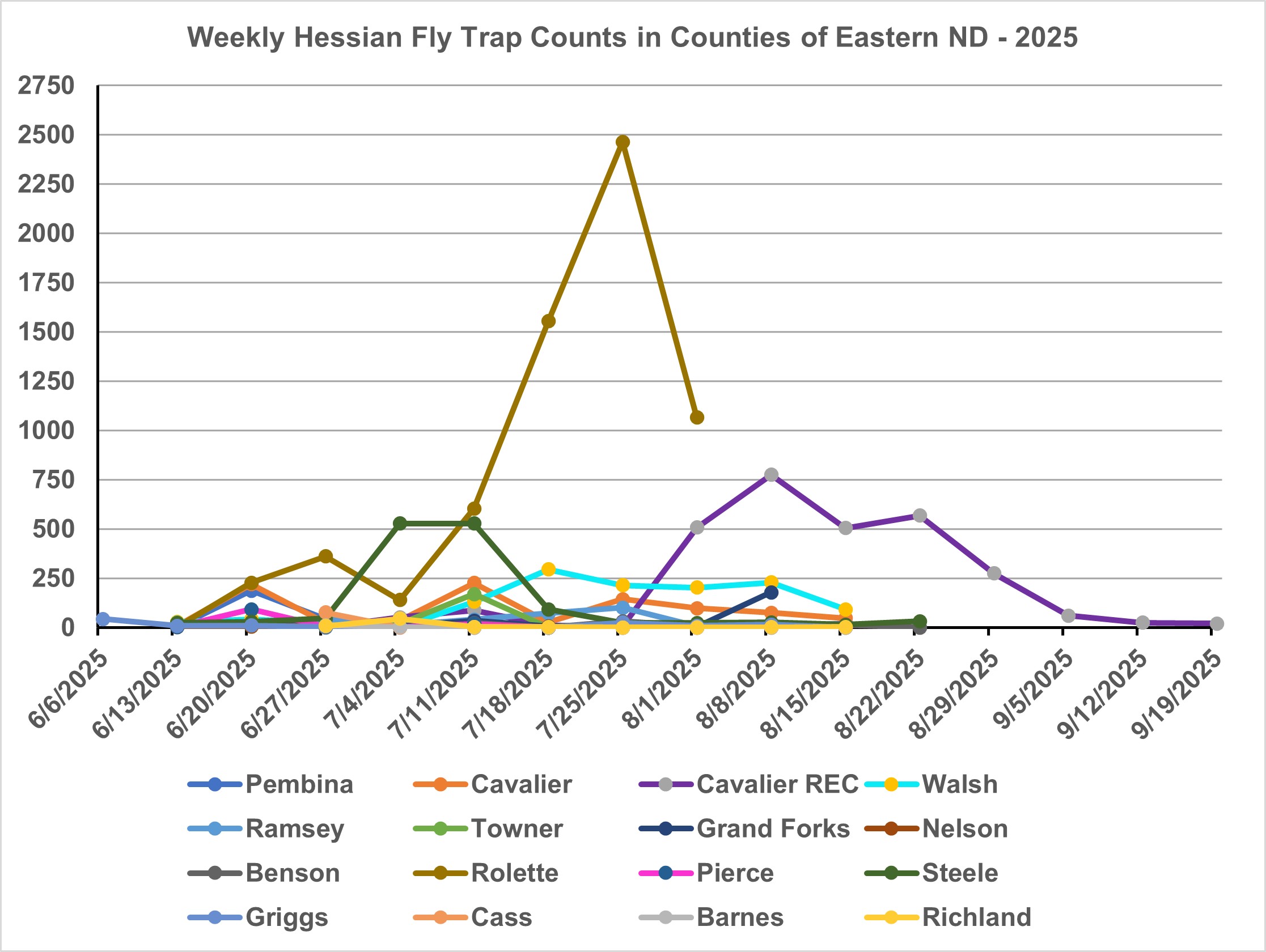

- Delayed adult emergence, occurring from late June to early July, as indicated by consistently low adult fly captures in pheromone traps across all locations in North Dakota in 2025 (Figure 1);

- Early‐stage infestations occur at the crown region of wheat seedlings, where sampling requires pulling plants from the soil, which may dislodge larvae or pupae and lead to underestimation of infestations.

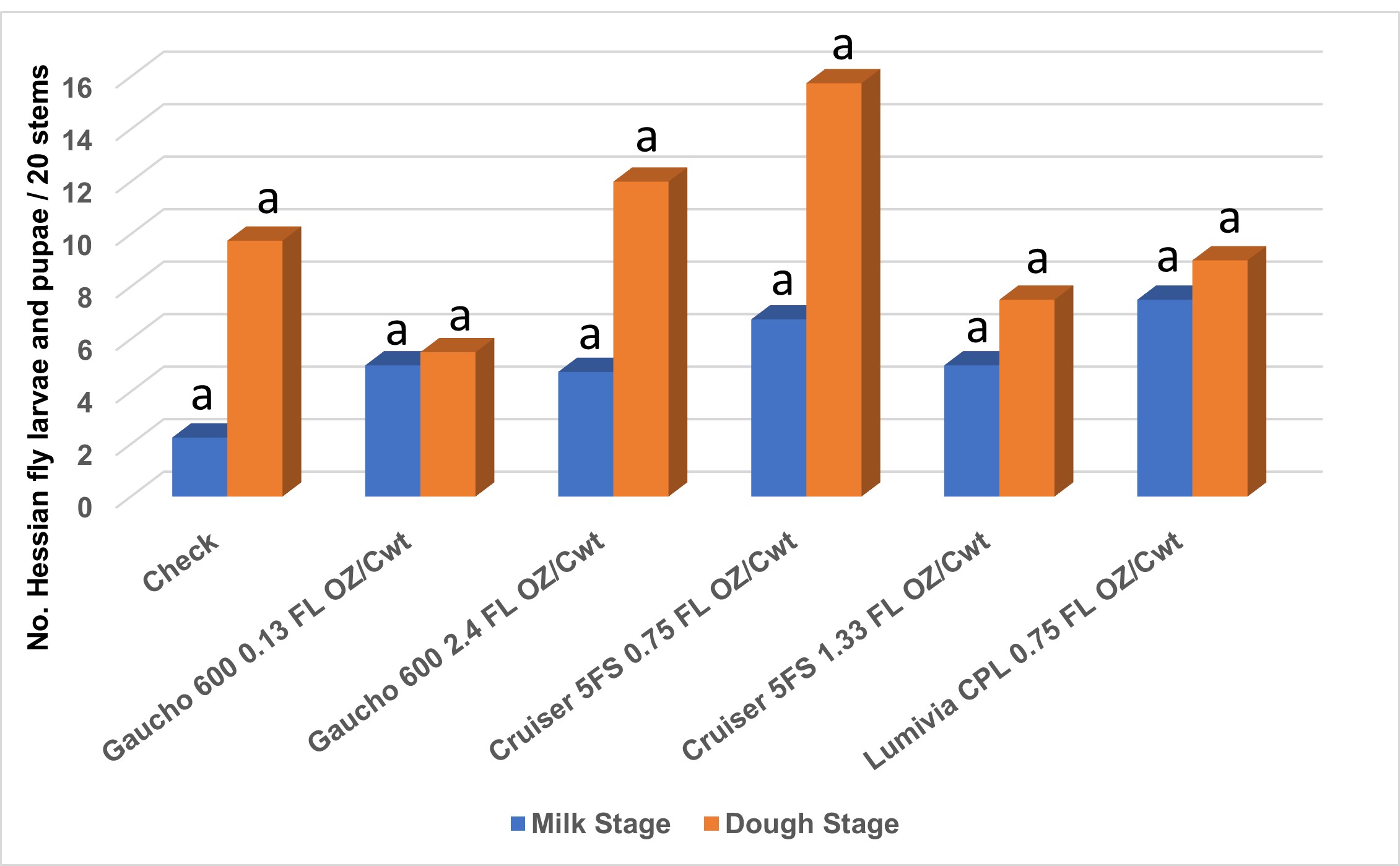

Hessian fly larvae were first observed during the third sampling event and pupae during the fourth, corresponding to the milk and dough stages of wheat development, respectively. These findings indicate that fly activity began late in the season—around the early boot stage—and continued through flowering. Treatment means for larval and pupal counts are presented in Figure 2 and Table 3, with yield data also summarized in Table 3.

No significant differences among treatments were found for plant stand, larval counts at the milk stage, or pupal counts at the dough stage. Mean larval counts at the milk stage ranged from 2.25 larvae per 20 stems in the untreated check to 7.5 larvae per 20 stems in the Lumivia treatment. Interestingly, the untreated check had the lowest number of larvae and pupae compared with all insecticide seed treatments. At this time, the most plausible explanation is that the efficacy of the seed treatments had diminished by the time flies were active and ovipositing.

At the dough stage, pupal counts increased across all treatments, although differences among treatments remained statistically insignificant. The lowest mean pupal numbers were recorded in Gaucho 0.13 fl oz, followed by Cruiser 1.33 fl oz and Lumivia 0.75 fl oz. These three treatments also showed the smallest increases in pupal counts from the milk to dough stages. In contrast, the untreated check, Gaucho 2.4 fl oz, and Cruiser 0.75 fl oz exhibited higher pupal counts and larger increases between growth stages (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Weekly trap catch data of Hessian flies in eastern counties of ND.

| Date | Pembina | Cavalier | Cavalier REC | Walsh | Ramsey | Towner | Grand Forks | Nelson | Benson | Rolette | Pierce | Steele | Griggs | Cass | Barnes | Richland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6/6/2025 | 43 | |||||||||||||||

| 6/13/2025 | 4 | 10 | 28 | 12 | 25 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 23 | 9 | |||||

| 6/20/2025 | 187 | 220 | 42 | 20 | 5 | 22 | 6 | 227 | 92 | 28 | 10 | |||||

| 6/27/2025 | 43 | 24 | 0 | 26 | 43 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 360 | 3 | 46 | 4 | 76 | 12 | 7 | |

| 7/4/2025 | 16 | 36 | 51 | 1 | 13 | 19 | 5 | 1 | 139 | 3 | 527 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 44 | |

| 7/11/2025 | 0 | 226 | 88 | 131 | 40 | 169 | 34 | 4 | 23 | 603 | 18 | 527 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 7/18/2025 | 13 | 25 | 8 | 295 | 72 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1554 | 0 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 7/25/2025 | 0 | 144 | 6 | 214 | 100 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 32 | 2463 | 4 | 23 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8/1/2025 | 3 | 97 | 507 | 203 | 6 | 13 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 1065 | 0 | 23 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 8/8/2025 | 4 | 75 | 774 | 229 | 18 | 17 | 178 | 22 | 4 | 8 | 25 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 8/15/2025 | 21 | 47 | 504 | 92 | 3 | 12 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||||

| 8/22/2025 | 567 | 0 | 32 | |||||||||||||

| 8/29/2025 | 274 | |||||||||||||||

| 9/5/2025 | 60 | |||||||||||||||

| 9/12/2025 | 24 | |||||||||||||||

| 9/19/2025 | 20 |

Figure 2: Mean number of Hessian fly pupae for insecticide seed treatments at milk and dough stages.

Bars of the same color that share the same letter are not significantly different (P<0.05).

| Treatment | Milk Stage | Dough Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Check | 2.25 | 9.75 |

| Gaucho 600 0.13 FL OZ/Cwt | 5 | 5.5 |

| Gaucho 600 2.4 FL OZ/Cwt | 4.75 | 12 |

| Cruiser 5FS 0.75 FL OZ/Cwt | 6.75 | 15.75 |

| Cruiser 5FS 1.33 FL OZ/Cwt | 5 | 7.5 |

| Lumivia CPL 0.75 FL OZ/Cwt | 7.5 | 9 |

Yield

Average yields across treatments ranged from 57.15 to 62.3 bu/ac. In contrast to the larval and pupal counts, significant differences were observed among treatments for yield. The higher rate of Gaucho (2.4 fl oz) produced the greatest yield (62.3 bu/ac), which was significantly higher than both the lower rate of Gaucho (0.13 fl oz) and the Cruiser 0.75 fl oz treatment (Table 3).

Although not statistically significant, a similar pattern was observed within the Cruiser treatments: the lower rate yielded 59.38 bu/ac compared with 61.8 bu/ac for the higher rate. The untreated check and the Lumivia treatment performed comparably to treatments 3, 5, and 6, with all producing yields exceeding 60 bu/ac (Table 3).

Table 3: Mean number of Hessian fly pupae for insecticide seed treatments at milk and dough stages and Yield.

Treatment | Mean No. of Larvae or Pupae/20 stems |

Plant Stand (Plants/ft2) |

Yield (bu/ac) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Milk Stage |

Dough Stage | ||||

1 | Check | 2.25 a | 9.75 a | 27 a | 60 ab |

2 | Gaucho 600 0.13 FL OZ/Cwt | 5.0 a | 5.5 a | 27 a | 57.15 c |

3 | Gaucho 600 2.4 FL OZ/Cwt | 4.75 a | 12.0 a | 24 a | 62.3 a |

4 | Cruiser 5FS 0.75 FL OZ/Cwt | 6.75 a | 15.75 a | 25 a | 59.38 bc |

5 | Cruiser 5FS 1.33 FL OZ/Cwt | 5.0 a | 7.5 a | 26 a | 61.8 ab |

6 | Lumivia CPL 0.75 FL OZ/Cwt | 7.5 a | 9.0 a | 25 a | 60.23 ab |

| Mean | 5.2 | 9.92 | 26 | 60.15 |

| CV % | 98.5 | 52.2 | 12.6 | 2.8 |

| LSD | 7.73 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 2.53 |

| P-value (0.05) | NS | NS | NS | 0.008 |

Means within a column that share the same letter are not significantly different (P<0.05).

Because no treatment differences were detected in larval or pupal counts, and because the yield of the untreated check was similar to that of four of the five seed treatments, the observed yield differences cannot be attributed to seed treatment efficacy against Hessian fly.

Conclusion

These results indicate that insecticide seed treatments alone may not effectively suppress Hessian fly populations in spring wheat in North Dakota. The late-season emergence of adult flies suggests that infestations occurred after the residual activity of seed treatments had diminished.

However, the presence of larvae at the milk stage and pupae at the dough stage highlights the potential value of integrating foliar insecticide applications at the boot and flowering stages with seed treatments. Additional research combining seed treatments and timely foliar sprays may provide improved management of Hessian fly under North Dakota conditions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the North Dakota Wheat Commission for financial support and our field crew, Lawrence Henry and Rick Duerr in planting and harvesting the trial.

References

Buntin, G. D. 2025. Hessian Fly (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) management using seed treatments in winter wheat. Journal of Entomological Sciences, 60(1): 129-140.

Howell, F.C., D. D. Reisig, H.J. Burrack, and R. Heiniger. 2017. Impact of imidacloprid treated seed and foliar insecticide on Hessian fly abundances in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Crop Protection, 98: 46-55.

Knodel, J. 2015. Hessian fly damaged wheat. North Dakota State University Crop and Pest, Report no. 15, August 13, 2015, Fargo, ND.

Schmid, R. B., A. Knutson, K. L. Giles, and B. P. McCornack. 2018. Hessian fly (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) biology and management in wheat. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 9: 1-12