Evaluation of Soils for Suitability for Tile Drainage Performance

(SF1617, Revised August 2025)The presence of salts and high water tables in North Dakota soils due to an extended climactic wet cycle recently has stimulated interest in the installation of tile drainage systems. The tile controls the water table and encourages the leaching and removal of salts from the soil above the tile lines. This improves soil productivity, culminating in improved crop yields

L.J. Cihacek Professor, Soil Science

N. Kalwar Extension Soil Health Specialist

B. Goettl Extension Soil Specialist

L. Prasad Extension Water Engineer

The purpose of a properly designed and installed tile drainage system when properly functioning is to drain excess, non-plant available soil water in a timely manner. This helps maintain groundwater levels at desired depths providing aerated soil conditions in the plant root zone that promotes good plant growth and productivity. It also promotes early-season warming of the topsoil to provide a favorable environment for seed germination and seedling establishment.

Periods of excess precipitation may bring groundwater levels nearer to the soil surface in farm fields throughout North Dakota. Groundwater near the surface reduces oxygen in these saturated soil layers, resulting in an unfavorable growth environment for plants.

In addition, the shallow groundwater can have high levels of water-soluble salts and sodium (Na+), leading to increased soil salinity and sodicity.

The higher levels of soluble salts are due to marine shale materials in glacially deposited parent materials where, in many places, the parent material is in contact with underlying Na+-rich shale bedrock. Weathering of the soil parent material and the underlying shale releases salts and Na+ into the groundwater.

In lower field areas (Figure 1), shallow groundwater depths (Figure 2, Page 2) can bring excessive salts and Na+ to the surface (Figure 3, Page 2) or they can accumulate below the surface in the plant rooting zone (Figure 4, Page 2). Through time, water evaporates from the soil surface, leaving behind an accumulation of excess salts and Na+. Soils with groundwater depths within 6 feet of the surface (shallower than 2 meters) are highly susceptible to developing salinity or sodicity problems (Seelig, 2000).

The combination of shallow groundwater and high soil salt and Na+ results in moderate to severe crop yield losses. These factors provide the impetus for many farmers and landowners to install subsurface (tile) drainage systems.

During wet weather and with good soil water infiltration, tile can drain excess water in a timely manner. Properly functioning tile systems maintain groundwater depths at desired levels and allow for leaching and removal of water-soluble salts.

In addition, soils with good drainage show improved soil productivity and crop yields. Other advantages of drainage include lower crop production risks, more water and cropping management options, reduced seasonal wetness and improved timeliness of field operations.

On the other hand, the cost of installation and maintenance, wetland determination issues, outflow management, need for water in dry seasons and strained relationships with neighbors may be disadvantages associated with tile drainage.

Although tile drainage is usually successful, instances may occur where the tile functions properly when first installed, but within a few growing seasons, areas in fields may not drain as expected. This situation may develop because of changes in soil chemistry due to the removal of salts and resulting soil swelling and dispersion rather than improper installation of the tile drains. Due to the high cost of tile installation, poor subsurface drainage performance can have a significant economic impact on a farming operation.

The loss of subsurface drainage effectiveness may be partially due to the tile being placed in or below a zone of sodic or saline-sodic subsoils or below restrictive clay layers (Figure 5). The sodic or saline-sodic characteristics are often not readily noted at the soil surface. Characteristics of saline, sodic and saline-sodic soils are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of saline, sodic and saline-sodic soils (from UDSA Handbook No. 60).

| Soil Type | pH | Electrical Conductivity (EC)* | Exchangeable Sodium Percentage (ESP) | Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) |

| ----- mmhos/cm ----- | --------- % --------- | |||

| Saline | <8.5 | >4 | <15 | <13 |

| Sodic | >8.5 | <4 | >15 | >13 |

| Saline-sodic | ≤8.5 | >4 | >15 | >13 |

| *mmhos/cm - millimhos per centimeter; 1 mmhos/cm = 1 deci-Siemen per meter (dS/m) | ||||

Tile installed in soils or subsoils that are sodic or saline-sodic often will function normally for a period of time after installation because these soils often contain divalent (2+ charged) calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) salts that keep the soil in an adequately flocculated state (maintain soil structure) under natural moisture conditions. But when the soils are drained and excess water is removed, the divalent salts also are removed, with the water leaving the soil material above or around the tile line saturated with monovalent (1+ charged) sodium (Na+).

When this occurs, the soils lose their natural structure and become dispersed. This can cause sealing of the soil above and/or around the tile lines, resulting in ineffective drainage. In addition, if sodicity starts from the surface layers/topsoil, it will further reduce the soil water infiltration, resulting in increased runoff or rainwater standing in a low spot despite tile installation (Figures 5 and 6).

Reduced drainage performance is more likely to occur in fine-textured (silty or clayey) soils and to a much lesser extent in coarser-textured (sandy) soils or where subsurface layering of soils occurs of different soil textures (Figure 7). Once drainage performance is reduced, little can be done economically to restore the effectiveness of the drainage system.

However, producers can take precautions prior to tile installation on soils where drainage performance may be affected. These precautions include: (1) examining the characteristics of the soil series (soil types) in the field under consideration for drainage, (2) evaluating the soil chemical characteristics for each of the soils mapped in the field, (3) evaluating the soil properties for suitability to install tile and (4) verifying soil types and chemical characteristics (items 1 and 2 above) by deep soil sampling and testing. Using these precautions can help avoid installation of tile in areas where poor subsurface drainage performance is likely.

standing water at a low spot on Sept. 13, 2019, due to the poor soil water infiltration resulting in reduced drainage performance. The main drain is indicated by the arrow.

Knowledge of Soil Series

The occurrence of a specific soil series, types or map units on a parcel of land under consideration for tiling can be obtained from a county soil survey map or online from the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Web Soil Survey (http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov). The soil series listed in Table 2 and Table 3 are soils that are most likely to have dispersion problems when drained.

Also, soils with the greatest probability of drainage problems are those soils with pH values greater than 8.5 in the surface or subsurface zones. A pH greater than 8.5 often indicates high sodium (Na+) saturation, which could lead to tile sealing when salts are leached out of the soil above the tile line. If any of the soils listed in Tables 2 and 3 occur in the parcel of land to be drained, the soil chemical characteristics need to be evaluated.

| Table 2. Soil series with sodium-affected subsoils. | ||

| Aberdeen | Heil | Noonan |

| Camtown | Larson | Ojata |

| Cathay | Lemert | Playmoor |

| Cavour | Letcher | Ranslo |

| Cresbard | Ludden | Ryan |

| Daglum | Manfred | Stirum |

| Easby | Mekinock | Totten |

| Exline | Miranda | Turton |

| Ferney | Nahon | Uranda |

| Harriet | Niobell | |

| Table 3. Soil Series with the potential for sodium-affected subsoils. | ||

| Antler | Glyndon | Moritz |

| Arveson | Grano | Nielsville |

| Augsburg | Grimsted | Northcote |

| Bearden | Gunclub | Putney |

| Bohnsack | Hamerly | Regan |

| Borup | Hedman | Reis |

| Clearwater | Hegne | Rockwell |

| Colvin | Holmquist | Roliss |

| Cubden | Huffton | Rosewood |

| Divide | Karlsruhe | Thiefriver |

| Eaglesnest | Kratka | Ulen |

| Elmville | Koto | Vallers |

| Enloe | Lamoure | Viking |

| Fargo | Lowe | Wheatville |

| Fossum | McKranz | Winger |

| Fram | Mantador | Wyndmere |

| Gilby | Marysland | Wyrene |

Most drainage system designers and installers evaluate soil texture in a field as a part of the system design process. However, soil chemical char-acteristics are not normally part of this process. Preliminary evaluation of soil chemical characteristics can be accom-plished by utilizing soil chemical data embedded in the Web Soil Survey. In addition, a soil drainage suitability rating for North Dakota soils is available in the Web Soil Survey.

Using the Web Soil Survey

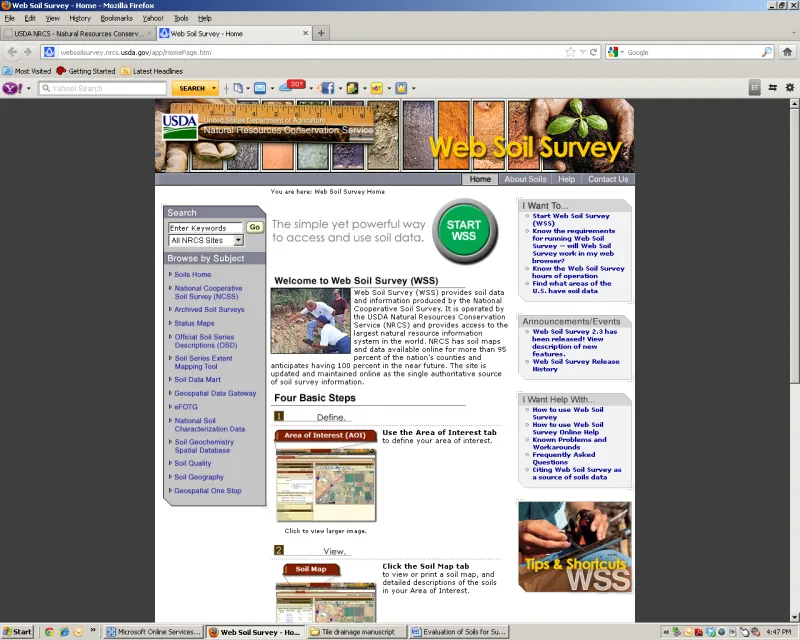

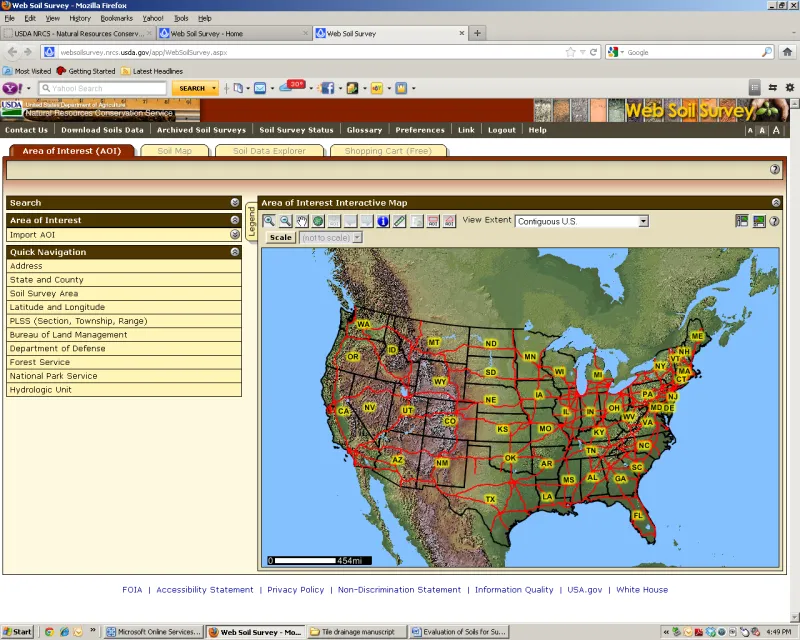

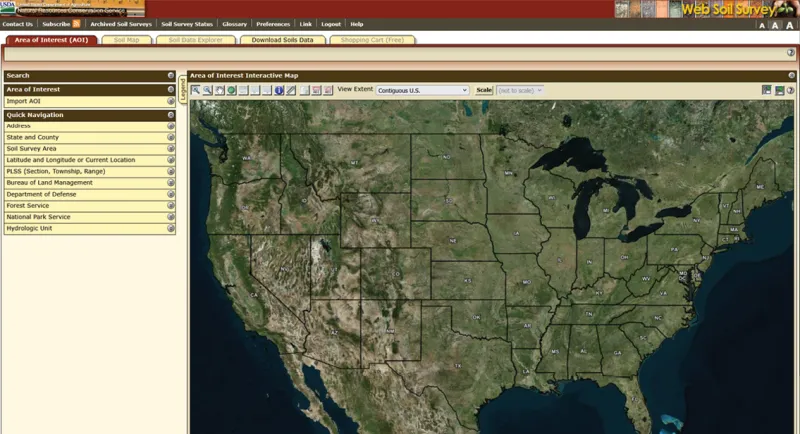

The Web Soil Survey is an internet-based digital product provided by the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service at http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov (Figure 8). Most soils in North Dakota can be evaluated from maps and information contained in the Web Soil Survey (Figure 9, Page 6). The following illustrations are an example of how to access this information from a personal computer or other device with internet access.

Evaluation of Soil Chemical Characteristics

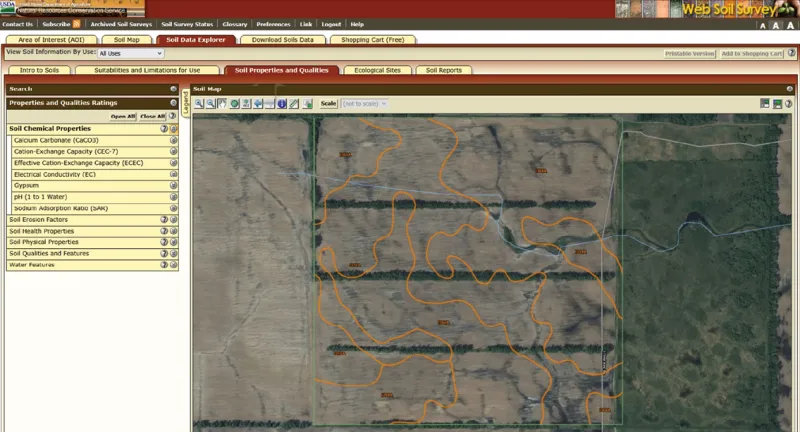

Soil chemical properties can be evaluated utilizing the “Soil Data Explorer” tab in the Web Soil Survey. Once a parcel of land is selected (Figure 10, Page 7), choosing the “Soil Chemical Properties” menu within “Soil Data Explorer” provides options for soil evaluation that will bring up a menu of several chemical characteristics that can be evaluated (Figure 11, Page 8).

For this soil evaluation, the character- istic of interest is “Sodium Adsorption Ratio” (SAR). Clicking on “Sodium Adsorption Ratio” will bring up an interactive area where depths to be evaluated can be specified in inches or centimeters (cm). A general evaluation of SAR to a depth of 5 feet (150 cm) can provide a realistic evaluation of soil chemical properties. However, for greater accuracy, the evaluation should be carried out for successive 1-foot increments to a minimum depth of 5 feet or at least 2 feet below the deepest depth of the drain line.

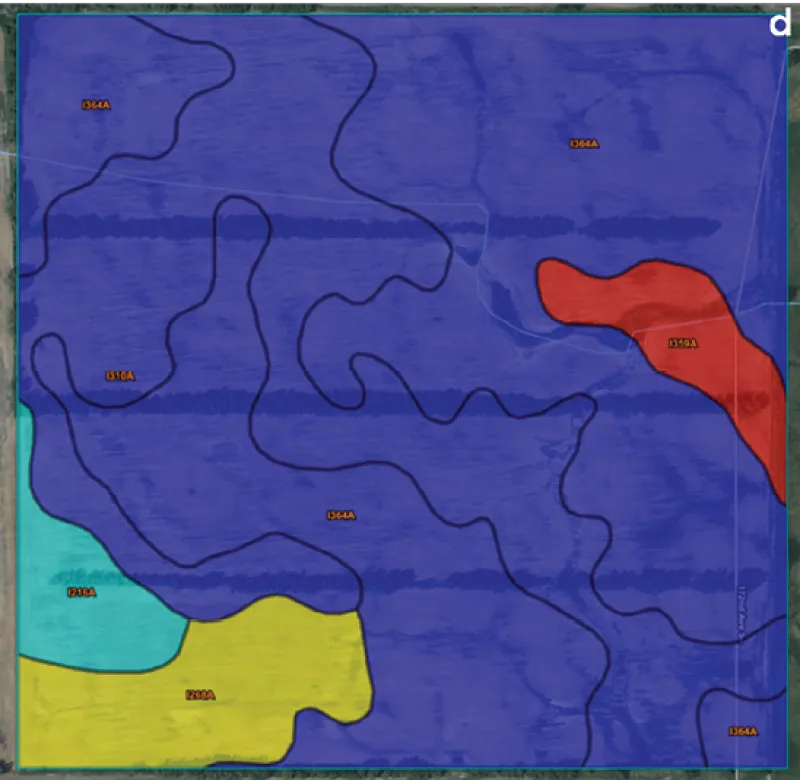

For each increment, a colored field map will appear over the photo base map showing the level of hazard related to each soil type (Figures 12a-d, Page 9). A table with an interpretation and average electrical conductivity (EC) or SAR values accompanies the map and interpretative information. Within this evaluation, red, green and yellow generally indicate lower hazards, while blues indicate higher hazards. Dark blue indicates the highest hazard.

Maps for each depth increment can be printed for reference. The information contained in these evaluations is generalized for each soil series or map unit based on the total composition of the map unit. The data for each map unit is populated with chemical and physical property information that is aggregated from various soil laboratories and the National Soil Survey Laboratory.

This information may change from time to time as the database is updated. Also, colors indicating the degree of hazard may vary from county to county within the Web Soil Survey.

You have four options for evaluating the soil layers in each mapping unit. Because each soil mapping unit includes small areas of varying sizes of soils that may not be suitable for drainage, the worst-case scenario should be utilized to identify soils that can contribute to problems with subsurface drainage.

The four choices for soil map unit evaluation are the following: (1) evaluation of all soil components, (2) evaluation of dominant soil components, (3) evaluation of dominant soil condition and (4) evaluation of a weighted average of all soil components. Figures 12a-d illustrate the comparison of these four choices for a general evaluation of the 5-foot (150 cm) depth zone of an actual parcel of land with sodium-affected subsoils. The numerical ratings for the field shown in Figures 12a-d are shown in Table 4, Page 8.

As shown in Table 4, evaluating the soil map units on the basis of all components will give the ratings for the most limiting soils within the map unit and provide for identification of the highest risk (or worst case) scenarios.

Data embedded in the Web Soil Survey is based on typical characterization sites across the normal geographic range of the occurrence of a specific soil type. Due to natural variability, the soils in the parcel of interest may vary from the “typical” map unit of the soil designated when the soil survey was conducted.

In addition, detailed variability and small inclusions within a soil map unit are difficult to show at the scale of typical soil surveys. Thus, a more detailed survey of the field to be drained will be useful for determining whether problems with subsurface drainage may exist.

All soils with an SAR value of 6 to 12 should be sampled for detailed chemical characterization. A qualified professional soil scientist or classifier should be consulted when making these evaluations.

Table 4. The soil SAR ratings for the field shown in Figures 12a-d based on soil chemical data from the Web Soil Survey.

| Map Unit Symbol | Map Unit Names | Web Soil Survey SAR Rating | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Components† | Dominant Component‡ | Dominant Condition§ | Weighted Average of All Components¶ | ||

† All soils normally occurring in a map unit. ‡ The major soil(s) making up a map unit. § The usual state of the soil chemistry of the major soil(s) in a map unit. ¶ The average rating based on the normal relative proportions of all soils in a map unit. | |||||

| I216A | Wyndmere fine sandy loam, 0-2%slopes | 7.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 3.9 |

| I268A | Foldahl loamy fine sand, 0-2% slopes | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| I310A | Arveson fine sandy loam, 0-1% slopes | 7.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| I359A | Hamar loamy fine sand, 0-1% slopes | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| I364A | Hecla-Garborg-Arveson complex, 0-2% slopes | 7.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

Subsurface Soil Drainage Suitability Rating

A soil drainage suitability interpretation has been incorporated into the Web Soil Survey. This rating evaluates all soils in a soil mapping unit using three criteria: installation, performance and tile water outflow quality. The information used for the evaluation of each criterion is shown in Table 5.

| Table 5. Criteria evaluated in subsurface drainage suitability ratings for subsurface water management in the Web Soil Survey. | |||

| Installation | Performance | Outflow Quality | Agronomic Concerns |

| Depths to bedrock or cemented pan | Presence of dense layers in soil | Soil salinity | Plant establishment |

| Stability of excavations | Soil permeability | Pesticide and nutrient potential | Plant growth |

| Amount of soil clay | Flooding | Soil cracking potential | Soil erosions |

| Presence of stones | Surface pH | Physical limitations | |

| Slope gradient | Soil sodium content Soil gypsum content Soil subsidence Sedimentation | Pesticide and nutrient management | |

The suitability rating provides a scale of 0 to 1 for each of these criteria and provides a weighted rating based on the components of a soil map unit. A rating near 0 indicates no limitations for subsurface drainage, while a rating near 1 is very limited.

Soils with a rating greater than 0.15 for SAR performance should be subject to verification by soil sampling and testing. The SAR suitability ratings for soils based on the soil chemistry evaluation described above are shown in Table 6.

| Table 6. Interpretation of soil SAR values and subsurface drainage suitability ratings for suitability of soils for drainage. | ||

| SAR Values1 | Drainage Suitability Rating2 | Interpretation |

| < 6 | < 0.15 | No limitation |

| 6-10 | 0.15-0.80 | Somewhat limited |

| >10 | >0.80 | Very limited |

| 1 Based on data from Springer (1997). 2Based on Web Soil Survey. | ||

This tool may give limitation ratings for multiple factors for each soil in a mapping unit. While most limiting factors are based on soil properties that do not change with drainage or management, soil SAR and EC factors are subject to change as soils are drained. However, other limitations identified by using this tool may respond to modifications in design and installation.

What the soil drainage suitability rating will not provide is a comprehensive site evaluation, determination of wetlands and flooding issues or soil productivity or design information, and it will not address social or environmental issues.

The soil drainage suitability rating is not designed to tell the landowner, land manager or tile installer that a field should or should not be drained. The rating is mainly designed to present information that a decision maker can use in making a decision whether drainage is a suitable option as a land treatment.

Verification of Soil Properties by Soil Sampling and Soil Testing

Once soil areas that have a moderate or severe SAR hazard are identified, these areas should be sampled to the proposed depth of the tile line in 1-foot increments. The soils should be sampled at a minimum of three locations within each soil map unit where an SAR hazard has been identified.

Samples from these locations can be composited into one sample for each depth increment. A minimum of one composite soil sample should be submitted for each five acres of a soil map unit in question.

Each soil depth increment should be analyzed for electrical conductivity (EC) and SAR using standard soil saturation paste extracts for the evaluation. This allows for making direct comparisons with the information contained in the Web Soil Survey database to verify the suitability for subsurface drainage.

If the soil analyses indicate that the SAR values are lower than the values shown in Table 6, then the soil is likely suitable for subsurface drainage. If soils are rated unsuitable for tile drainage, then alternatives such as leaving the soil area undrained or placing the area into permanent cover should be considered. Utilizing registered professional soil scientists or NRCS soil scientists can assist in making decisions about alternatives to subsurface drainage.

The ratings shown in Table 6 are only a guide for drainage suitability. Dispersion of the soils under subsurface drainage conditions depends on several factors, including the composition of soil minerals, soil texture, composition of shallow groundwater and composition of soil salts. You also should recognize that soils subject to dispersion may be localized or only be a small proportion of the soils in the field or land parcel to be drained.

Evaluating soils for subsurface drainage suitability prior to installation can reduce the incidence of poor tile performance and unrecoverable installation costs. If soils susceptible to poor drainage are identified prior to tile installation, then alternatives to drainage can be considered and implemented. Once soils disperse due to subsurface drainage, attempting to remediate the soils to near their original internal drainage condition is extremely difficult and costly.

Additional Considerations of Tiling

Cost and environmental suitability are major considerations when deciding to install drain tile systems. The following questions should also be considered when considering when deciding to install tile drain systems:

1. Is water standing in fields due to a high shallow water table, or is it due to poor permeability of the soil? Tile drains are usually installed at a 3-4 ft. depth below the soil surface. A tile drain can lower a shallow water table near the soil surface. However, if water infiltration or soil permeability is low, surface water may not be able to reach the soil zone within which the tile drain is installed. In other words, tile drainage does not improve soil permeability because that is a natural property of the soil.

2. Are there enough rain events each year that create saturated soil conditions and lead to high shallow ground water tables during planting, crucial plant growing stages and harvest times on a consistent basis (e.g., every year versus two or three times in 10 years)? Necessity versus convenience needs to be considered when making decisions of cost-effectiveness of tiling systems.

3. Is soil sodicity (high SAR) present in soil depths above or around the deepest depth proposed for fields in consideration for tiling? High sodicity at these depths are extremely difficult to amend due to the large quantities of amendment needed to effectively treat the volume and quantity of soil affected. If soil permeability is highly restricted by sodium or high soil clay, normal surface applications will leach into the soil at a very slow rate at which the remediation may take decades to be accomplished.

Related NDSU Extension Publications

Franzen, D., H. Kandel, C. Augustin and N. Kalwar. 2013. Groundwater and Its Effect on Crop Production. North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D. https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/ag-hub/publications/2013-groundwater-and-its-effect-crop-production

Franzen, D., N. Kalwar, B. Goettl, and T. DeSutter. 2024. Sodicity and Remediation of Sodic soils in North Dakota. NDSU Extension publication SF1941. North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D.

https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/sodicity-and-remediation-sodic-soils-north-dakota

Kalwar, N., T. DeSutter, D. Franzen and C. Augustin. 2021. Soil Testing Unproductive Areas. NDSU Extension publication SF1809. North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D.

https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/soil-testing-unproductive-areas

Franzen, D., C. Gasch, C. Augustin, T. DeSutter, N. Kalwar, A. Wick. Managing Saline Soils in North Dakota. NDSU Extension publication SF1087. North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D.

https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/managing-saline-soils-north-dakota

Seelig, B.D. 2000. Salinity and sodicity in North Dakota Soils. NDSU Extension publication EB57. North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D. 16p.

https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/ag-hub/publications/2000-salinity-and-sodicity-north-dakota-soils

Additional References

Curtin, D., H. Steppuhn and F. Selles. 1994. Clay dispersion in relation to sodicity, electrolyte concentration, and mechanical effects. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 58:955-962.

McCauley, A., and C. Jones. 2005. Soil and Water Management Module 2: Salinity & sodicity management. Montana State University publication 4481-2. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT.

At: http://landresources.montana.edu/swm. Accessed June 20, 2020.

Oster, J.D., and F.W. Schroer. 1979. Infiltration as influenced by irrigation water quality. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 43:444-447.

Rengasamy, P. 2002. Clay dispersion. In ‘Soil physical measurement and interpretation for land evaluation.’ (Eds B.M. McKenzie, et al.) pp. 200–210. (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne).

Rengasamy, P., and Sumner, M.E. 1998. Processes involved in sodic behaviour. In ‘Sodic soils. Distribution, properties, management, and environmental consequences.’ (Eds M.E. Sumner and R. Naidu) pp. 35–50. (Oxford University Press: New York)

Springer, A.G. 1997. Water-dispersible clay and saturated hydraulic conductivity in relation to sodicity, salinity and soil texture. M.S. thesis. North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D.

Springer, G., B.L Wienhold, J.L. Richardson and L.A. Disrud. 1999. Salinity and sodicity induced changes in dispersible clay and saturated hydraulic conductivity in sulfatic soils. Commun. Soil Science Plant Anal. 30(15-16):2211-2220.

USDA Soil Salinity Laboratory Staff. 1954. Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils. Agriculture Handbook No. 60. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

The original publication was authored by Larry J. Cihacek, professor, Soil Science; Dave Franzen, Extension soil specialist; Xinhua Jia, professor, Agriculture and Biosystems Engineering; Roxanne Johnson, former Extension water quality associate; and Tom Scherer, Extension agricultural engineer, 2012.