Research

Our research explores how people’s experience with language affects the way they learn and use it.

Here are some of our current projects:

How do kids learn words with multiple meanings?

Many accounts of how children learn words rest on the assumption that each word will have one meaning and each meaning will have one word. There's only one problem with that assumption: it isn't true!

All languages have words with two or more unrelated meanings. How might children learn that a single word can have more than one meaning?

Using a method called cross-situational word learning (CSWL), we study this question by teaching children and adults new words. In a CSWL study, people hear new words paired with unfamiliar objects or animals, but each exposure is ambiguous with regard to which word goes with which object. Participants can only determine word-meaning pairs by keeping track of co-occurrence across the whole study. We manipulate different aspects of participants’ experience during this procedure to see what helps them learn more than one meaning for a new word.

This research is currently supported by NIH grant R15 HD115135-01.

How do children and their caregivers use words with multiple meanings?

In-lab experiments help us understand what kinds of information children can use to learn words with multiple meanings, but that information is only useful to children if they actually hear it.

We are working with previously recorded interactions between caregivers and children to determine how parents use words with multiple meanings when talking to their children, which will help us validate the sources of information that we test in our in-lab studies. We are also interested in when and how children themselves begin to use words with more than one meaning.

Are some language structures easier to learn than others?

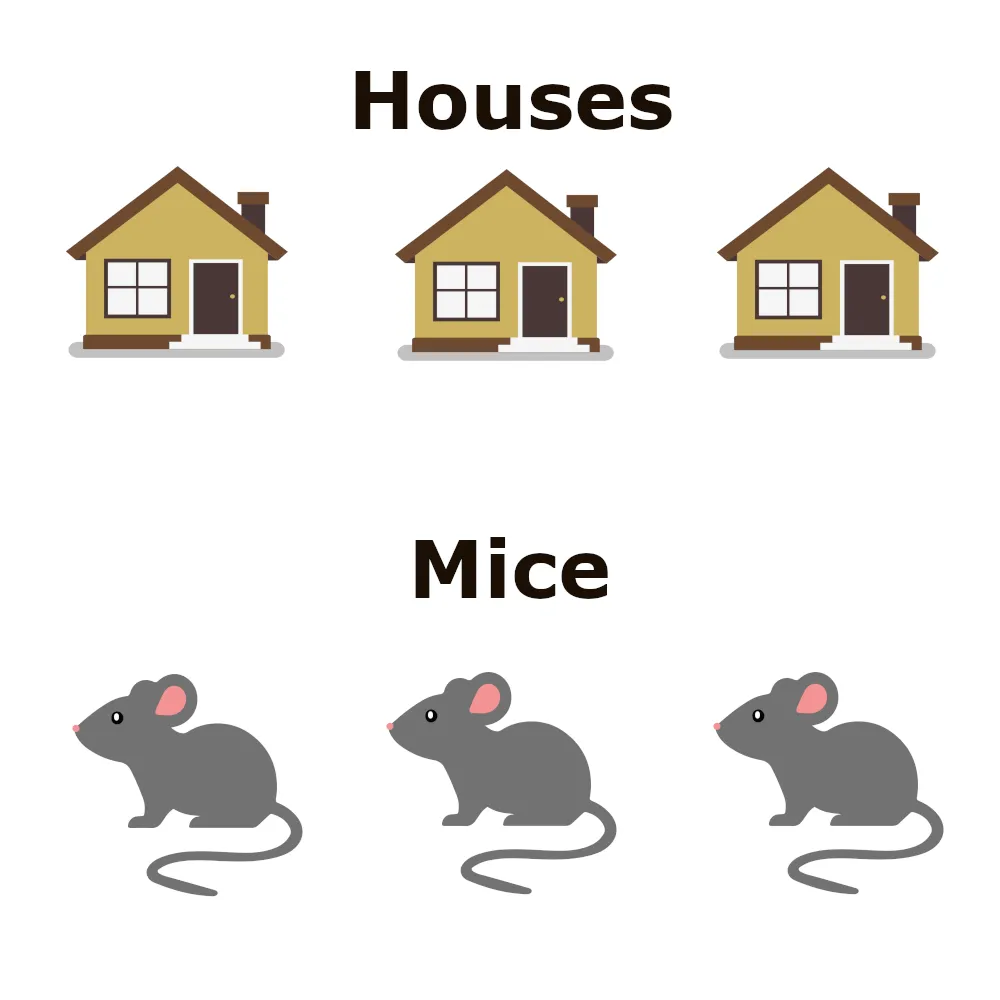

Different languages mark the same concepts in different ways. For example, most English words become plural with a suffix (house becomes houses), but Indonesian words become plural by being repeated (orang becomes orang-orang). Proficient users of a language can apply these general rules to new words. Natural languages also have exceptions, or irregular forms, that must be learned individually (mouse becomes mice). We might think that systems of marking these meanings that are easier to detect are easier to learn.

To study this, we create artificial languages that use different marking systems for plural and singular words to see how different cues affect production and comprehension, as well as how irregularities are affected by these differences.