Late Wet Spring Soil/Fertilizer Considerations

This page was adapted from the article, "Late Wet Spring Soil/Fertilizer Considerations" which appeared in Crop & Pest Report on May 12, 2022.

Here are some soil considerations before racing to the field in a late, wet spring.

West-river:

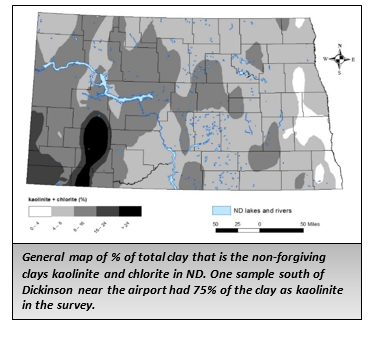

Most of the soils west of the Missouri River, with the exception of a remnant glaciated strip roughly 30 miles west/south of the river have a high amount of kaolinitic clay. Especially in sandier soils, such as those south of Dickinson, traffic over wetter than normal soils will probably result in hard to alleviate compaction. Kaolinitic clay is non-forgiving and the illite clays that dominate the rest of the clay fraction are only moderately forgiving. The small amount of smectitic clays that have shrink and swell properties will probably not be enough to help alleviate any compaction from hasty traffic this spring.

Fields west-river that are long-term no-till will maintain their superior aggregation and trafficability as long as the fields are not entered too soon.

For more information see North Dakota Clay Mineralology Impacts Crop Potassium Nutrition and Tillage Systems.

Central Region:

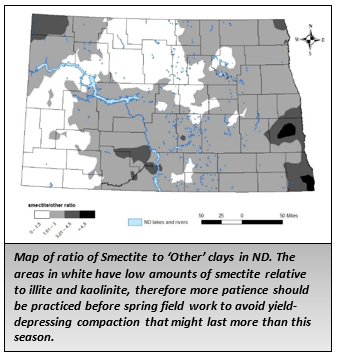

The white area in the smectite to other ratio map is higher in illite due to the old footprint of the glacial Souris River. These soils are more easily compacted than those in the more colored regions. Tilling/planting when the surface few inches are dry to just moist will help to reduce compaction this spring and reduce the need for deeper tillage this fall. Long-term no-till farmers should have little problem with compaction in this region if the crops are not ‘mudded in’.

Valley Region:

Except for the sandy region from Colfax west to Lisbon (Sheyenne Delta), this region is high in smectitic clays. It is possible to produce severe compaction if the crop is mudded in, then the weather turns dry (2012); but if mudded in, a half-inch rain shortly afterwards will mellow the soil greatly so that the crop will not suffer. Trying to decide whether to mud a crop in within the Valley is a ‘crap shoot’. The odds are usually in your favor of not having lingering effects, but there are some years when mudding a crop in has severe consequences for that year. In terms of long-term effects, a wetting and drying cycle is far more effective in removing compaction compared to a freeze-thaw cycle, at least below 6 inches in depth.

The Sheyenne Delta soils are not as forgiving as the rest of the Valley, so some patience should be practiced to avoid ruts during tillage/planting. Also, the water table is naturally high, and more so this spring. Therefore, planning to sidedress the corn would be a good strategy, as significant denitrification and N loss is possible with even modest rainfall from now on into the season if only preplant N were applied. Anhydrous, UAN, urea can all work. UAN sidedressed with a coulter is more efficient in a wet season as it doesn’t bring up much before 2 inches as anhydrous ammonia would, it wouldn’t need NBPT to slow urease activity like urea would.